Story and Photographs by David V. Craig

New Hampshire Profiles

January 1974 – Vol. XXIII – No. 1, pp. 70-79

Whatever happened to Thorwald Ericsson, brother of Leif and son of Eric the Red, who was killed by savages c. 1003 A.D.?

A group called the Historical Preservation Society thinks it may have found the answer. The particular object of its attention is a 600-pound boulder located in Hampton scarred with apparent runic inscriptions and traditionally held to mark the grave of Thorwald.

The H.P.S., consisting primarily of Hampton residents, was formed in June 1973 for the purpose of bringing into public awareness the presence of many potentially important archaeological sites in New Hampshire as well as a systematic evaluation of these sites. Specifically, the Norse Boulder (or Thorwald’s Rock, as it is variously called) was the “prime mover” in the formation of the society. And with good reason. The land upon which the boulder rests is presently (Nov. ’73) for sale. There is no way to predict the fate of the rock once the land has been sold or whether the new owners will be sympathetic to continuing research.

Whether or not the boulder does indeed indicate the grave of Thorwald Ericsson is almost a moot point. The fact is that there is enough history associated with the rock to warrant further study and, perhaps, its relocation to an area such as Tuck Green where it would be more readily accessible to citizens and tourists. [Since the original publication of this article, the stone has been moved to the grounds of the Tuck Memorial Museum.]

The first allusion to the rock seems to have been an entry in the diary of one Effie Taylor in 1670. At this point, it was referred to as “Witch’s Rock” and the local inhabitants were forbidden to go near it. Just why the boulder was held in such awe is not clear beyond the fact that these were generally superstitious times. Hampton had only been settled for thirty-two years by people whose imbedded beliefs and prejudices had been transplanted with them. Then too, the Indians had long considered the area taboo. Their legends spoke of a white god buried beneath the rock. Supposedly, no aboriginal artifacts have been discovered within a healthy radius of the site.

In the 1800’s a man with the unlikely name of Launcelot Quinn decided to settle once and for all the controversy surrounding the Norse Boulder. Fortified by “spiritous beverages,” he and several fellow adventurers threw caution to the wind and proceeded one night to the site. As the first shovel broke the earth, a lightning bolt struck close by and hurled them backwards, thereby hastily terminating the expedition if not their speculation.

The rock comes to light once again, this time in 1902 when a Philadelphia judge published a newspaper article in which he mentioned the rock had been “discovered” by his ancestors in the 1600’s on land granted to them by the English Crown.

There the matter rested until 1938 when Hampton celebrated its Tercentenary. In an effort to utilize as much local lore as possible, two archaeologists were hired to search out this mysterious stone. It was eventually located at its present site and dubbed Thorwald’s Rock.

For decades scholars and students of Viking history have attempted to pinpoint the various landfalls of the Norsemen using logical supposition and the Sagas —Eddaic accounts of early voyages — as their guides. While archaeological discoveries suggest large permanent encampments did exist in the Canadian maritime provinces, notably at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland excavated in 1960 and carbon-dated to c. 1000 AD., it is reasonably certain the Vikings made exploratory thrusts south along the Atlantic seaboard. The discovery of the Wilson-Braxton Tablet and the Kensington Stone indicate respectively that, excluding hoaxes, the Norsemen sailed as far south as Virginia and penetrated inland to Minnesota.

There is no question but what the Vikings had the means to follow their questing spirit on long voyages. Their ships were eminently seaworthy. The excavation of such crafts as the Gokstad Ship (1880) revealed the “secret” to their construction to be an exceptionally strong keel and thin planks to which sturdy timbers were lashed. To dispel any doubt that a Viking ship could have made a transoceanic voyage, a Norwegian named Niagnus Andersen built an exact replica of the Gokstad Ship and in 1893 sailed it from Norway to New York in forty days.

The Norsemen, then, certainly could have landed in New Hampshire, but did they? There are, undeniably, unnatural scarrings on the face of the Norse Boulder and they do not seem to be representative of Indian petroglyphs. Several authorities who have examined them agree they are runic in origin. A resident of Exeter translated the scars to read rather conveniently: “Thorwald Ericsson — 1004 A.D.” The late Olaf Strandwold, author of Norse Runic Inscriptions Along the Atlantic Coast and Norse Inscriptions on American Stones, deciphered the inscription to read: “Bui raised stone.” Bui was the name of a family of Norwegian seafarers, contemporaries of the Ericssons. Strandwold also dated the inscription to 1043 A.D., considerably after the Ericsson brothers conducted their New World explorations.

Whenever one authority presents a particular opinion, there is, of course, another who will offer the contrary. Aslak Liestol of the Universitetets Oldsaksamling in Oslo, Norway, made the following observations in April of 1972: “I am not familiar with this inscription, but I very much doubt its authenticity as a runic inscription from the times before Columbus. The lines depicted on the stone can not he read as an inscription without considerable assumptions and speculative alterations and additions, which also goes for the actual reading ‘Bui raised stone.'”

The opinion of Harold Fernald, historian and teacher of an anthropology class at Winnacunnet High School in Hampton, lies between the two extremes. “I believe,” says Fernald, “that the rock is sort of a ‘Kilroy-was-here‘ type of marker. The inscription is almost certainly runic, but rather than indicating a grave site, it probably serves as Nordic graffiti — the Vikings were in Hampton nearly a millenium ago and carved these inscriptions merely to mark their passing.”

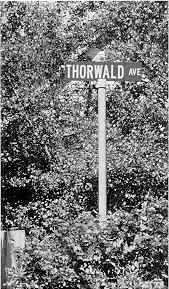

Mrs. Virginia Fraser, president of the Historical Preservation Society and a summer resident of Thorwald Avenue, feels differently. In her opinion, Thorwald’s remains do lie beneath the rock. “Not only does the geographical description as given in the Sagas fit the Hampton area,” she maintains, “the rock itself suggests he is buried there. There are two crosses carved on the rock, one near the top, the other near ground level. Traditionally, Thorwald’s dying words were ‘Bury me with a cross at my feet and head and call it Krossanes forever.'”

There are various accounts of Thorwald’s death and the events preceding it, the most reliable probably being a 15th-Century manuscript called Skálholtsbók. It recounts Eric the Red’s emigration from Norway to Iceland and then to Greenland prompted by killings for which he was held responsible. It was from Brattablid, Eric’s farm in Greenland, that the Ericsson brothers set out upon their explorations.

After Leif returned to Brattablid from his “Vinland” discoveries, Thorwald set out on his own voyage. He headquartered for more than a year at Leifsbudir (Leifs winter quarters — held by some to be on Great Bay).

It was during the second summer in Vinland that Thorwald kept his appointment with destiny. Caught in a sudden storm, his ship was blown ashore where it broke its keel. A new one was fashioned on the spot and the area designated Kjalarnes (Keel Head). Continuing his voyage, the ship passed around a promontory and into a “fjord.” The wooded scenery impressed Thorwald to the extent that he remarked “I should like to build myself a home here.”

His words were more prophetic than he realized. Three skin-covered boats were spotted upsidedown on the beach and, upon investigation, three Indians were discovered under each. Eight of them were killed. The ninth escaped. Even though a large settlement had been noticed deeper into the “fjord,” the Norsemen spent the night on the beach.

Early the next morning Thorwald was awakened by a premonitory voice warning him to get his men to the boat. The advice was well-founded as a fleet of skin-covered boats was at that very moment moving toward them. In the ensuing skirmish Thorwald was killed by an arrow which passed between his shield and the gunwale of his boat, penetrating his body beneath the arm. Before he died, he requested that he be buried on the promontory he had earlier admired. This, say the Sagas, was done and the site named Krossanes (Cross Head). His crew then sailed away, returning to Greenland the following spring.

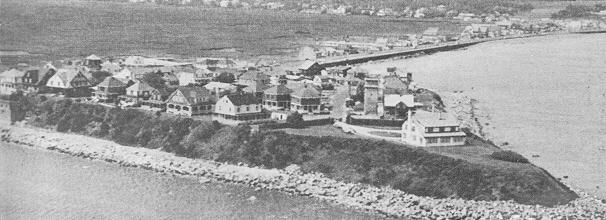

Probably the strongest indication that Thorwald Ericsson lies beneath the Norse Boulder is the geographical similarity between Hampton landmarks and those given in the Sagas. Any of the stretches of beach north of Hampton might serve as Kjalarnes, the spot where Thorwald beached his ship to construct a new keel. And there is a large promontory in Hampton called Great Boar’s Head and just south of it the Hampton River empties into the Atlantic. As further corroboration, in June of 1970 Professor Howard R. Sargent, then of the Sociology Dept. at Franklin Pierce College, discovered the remains of a large Indian settlement dating back considerably more than a thousand years in Hampton Falls just south of Hampton proper.

“Unfortunately, the area about the rock was once under water,” says Harold Fernald, “so any bones, if there ever were any, are likely to be leached out.”

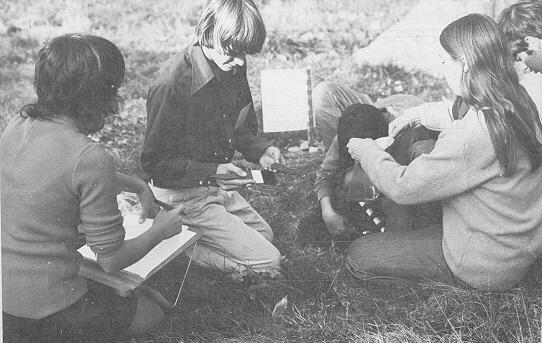

Fernald and his anthropology class, who will be excavating the site in November, hope to find such artifacts as iron religious trinkets that might have survived the encroachment of salt water.

There is, however, as Fernald points out, an immediacy to the situation, a sort of “emergency archaeology” as the stone has been repeatedly chipped for souvenirs making an accurate analysis of its significance increasingly difficult.

His sentiments are echoed by Mrs. Fraser of the H.P.S. According to her, one man threatened to take the entire rock as a souvenir as did several students from M.I.T. These were idle threats. More direct ones have arrived via the mail including a letter from the N.D.B.C. (No Discoveries Before Columbus), an organization whose purpose is self-explanatory.

And curiously, be it in support of further investigation or not, the ghost of Thorwald Ericsson has been seen from time to time over the years by those who live close by. “I was standing in front of my house one night very near to the Norse Boulder,” claims one such witness, “when I saw a helmeted and bearded figure moving in the fog. I’m not sure I care to believe in such things, but I was unnerved enough to go back into the house even though it was probably just one of the summer residents.”

Does Thorwald Ericsson lie beneath the strangely-carved rock in Hampton? Obviously, no answer will be forthcoming until the site is officially excavated this November.

In the meantime, the boulder sits there enigmatically — the tombstone of Thorwald Ericsson, a Viking landmark or, perhaps, just another rock in the Granite State.

Postscript:

Three test holes were dug around the Norse Boulder, the last on Wednesday, Nov. 14th. In each instance, the diggers hit hard-pan — firm unbroken ground — at a depth of approximately 42 inches, indicating that the soil had not been disturbed for some time below this level.

A strict archeaological procedure was observed. The earth was thoroughly sifted and each item too large to pass through the sifter was cleaned with a brush, then bagged and labeled. Unfortunately, beyond a 1973 penny, no man-made objects were found.

“We’ve established as far as we can determine,” states Harold Fernald, whose anthropology class conducted the digs, “that the area we covered has not been disturbed by man.

The question of whether the remains of Thorwald Ericsson lie in the immediate vicinity, however, still has not been definitely answered. It was learned that the stone was moved roughly 25 feet some years ago to make room for a bulkhead.

“To be absolutely sure,” Fernald points out, “the whole area would have to be dug up layer by layer.”

Oddly enough, this very move is being seriously considered by the Historical Preservation Society. Mrs. Virginia Fraser, president of the H.P.S., is attempting to secure state funds to undertake just such an endeavor.

And, perhaps, with good reason despite the discouraging results of the initial excavations. According to geologists, soil, when turned over, will return to a hardpan condition after six or seven hundred years. Thorwald, it will be remembered, was buried nearly a thousand years ago.

More than this, several authoritative sources have recently expressed interest in the Norse Boulder. A Mr. Ara Kleinseldt of the Historical Dept. of the Smithsonian Institution asked to be kept informed of the progress of the dig. A representative from Harvard plans to visit the site in the spring to determine by an undisclosed process whether or not there exists on the stone any portion of the runic inscription obliterated to the visible eye by the elements over the years.

In a way, it is fitting that so much attention should be paid to the Norse Boulder at this time. Records indicate that Thorwald Ericsson was born in late November of 973. The excavation of his supposed gravesite marks to the month his 1,000th birthday.