History Matters

By Cheryl Lassiter

Hampton Union, October 6, 2015

[The following article is courtesy of the Hampton Union and Seacoast Online.]

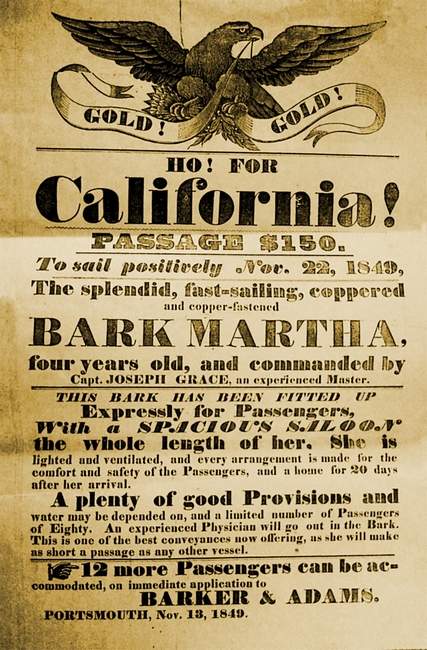

1849 Broadside for the Bark Martha. [Hampton Historical Society photo]

In the mid-19th century some anonymous wit applied the term “Argonaut”—from the Greek epic of Jason’s quest for the Golden Fleece—to the tens of thousands of men and women, including 13 from Hampton, whose own passionate seafaring quests for things of gold had begot the California Gold Rush of 1849.

Our Hampton Argonauts were descendants of Puritans who had brought to America a divine obligation to create a “city on a hill,” and they were right at home with the successor doctrine of Manifest Destiny. They read with interest President Polk’s annual message to the nation, which hailed the virtues of westward expansion and cited the abundance of gold in the California territory. Of course, not everyone was as sanguine as Polk: an Exeter Newsletter editor warned that the Argonauts’ land of gold was also the land of death. Maybe some cautious souls took heed and stayed at home. Not so the Hamptoners, who “took the fever” and went west.

The accidental Argonaut

It was purely a coincidence that 25-year-old Caroline Perkins Joyce was the first townie to rub up against the gold fields of California. Displaying the same independence of mind as her grandfather John Harriman, the half-Penobscot pastor of Hampton’s Baptist Church, Caroline defied her parents and joined the Church of Latter Day Saints in Boston. There she became known as the “Mormon nightingale” for her beautiful singing voice. In 1846, in company with several hundred other Mormons, Caroline, her husband John Joyce, and daughter Augusta sailed from New York on the ship Brooklyn, bound for California. This voyage proved historic, as it was the first to transport women and children around Cape Horn for the purposes of settlement.

When gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in January 1848, John Joyce deserted his plow and joined the rush for riches. “My husband has been in the gold mines,” Caroline wrote to her parents, “and in four months has dug out two thousand dollars’ worth of gold. Any boy twelve years old can get from one to three ounces of pure gold in a day.” Urging them to come out west where they could earn a better living, she posed the question, “Who would not leave home for a while and risk the ocean waves, rather than work for years?”

In 1849, Caroline’s father and brother, both named John, separately journeyed to California. As her daughter wrote years later, “My grandfather, and uncle, John Perkins, came to see my mother. I well remember sitting on grandpa’s knee and learning my alphabet from him. I recall when Uncle John sang the strange, pathetic, old-fashioned sea songs of which he knew so many and sang so sweetly.”

The gold fields enriched the Joyces but left a blight on their marriage. Caroline divorced her husband, remarried, and moved to the Utah Territory, where she died in 1876. Her tombstone in St. George, Utah commemorates her part in the historic voyage of the Brooklyn.

The Ark sails for California

On October 31, 1849, the 297-ton brig Ark, Captain Charles Marsh master, sailed from Newburyport. After a long passage around the Horn of 206 days and some 17,000 miles, the ship sailed into San Francisco Bay on May 25, 1850. On board were over 100 Argonauts, including three from Hampton: J. H. Williams, Fred L. Dunbar, and J. Perkins (this was either John Perkins, Caroline’s father, or Captain James Perkins, of the Tide Mill Road area).

What these men accomplished during their time in California is largely unknown. John Perkins returned home, apparently none the richer, built a house at the beach, and lived there until his death in 1876. James Perkins spent five years in California, and upon his return rebuilt his tide mill “with money he brought from California.” He died in 1894 at the age of 90.

Fred Dunbar stayed in the west, never having struck it rich. In 1870 he was working as a laborer in the Washington Territory, and was still there in the 1890s. J. H. Williams became “a word in the wind, a brother to the fog,” and his fate remains to be discovered.

The Domingo follows

The barque Domingo, Captain Bray master, sailed from Newburyport on November 12, 1849. The ship caught up to the Ark off the coast of Brazil, and although faced with a week of gales and hailstorms around the Horn, sailed into San Francisco Bay on April 6, 1850, nearly two months ahead of Marsh’s brig.

Among the Domingo’s passengers were six young Hampton men, the Parker Schnabel’s of their time: Nathaniel Johnson, Charles M. Perkins, Henry S. Lamprey, Charles T. Lamprey, Morrill M. Lamprey, and John E. Dearborn. It was a confusing mix of brothers-in-law, uncles, and cousins.

Excerpt from Charles Perkins's Journal, 1849-1862. [New Hampshire Historical Society photo]

From Charles Perkins’s journal, we know that Johnson, Perkins, Henry Lamprey, and Charles Lamprey had formed a company for the purpose of mining gold. After arriving in San Francisco, they set out for the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, eager to get scratchin’. They soon were mining various claims in the Curtis Creek area, graduating from picks and pans to the Long Tom, a gold washing contraption that required four men and a good stream of water to operate. For a time, each man was earning about one hundred dollars a month in gold.

In May 1851 they sold out and headed home. About this homeward journey, there’s a rural legend of sorts that points to theft and deception on the part of Charles Perkins. It goes like this: Johnson decided to take the longer route around the Horn, and he entrusted his gold to Perkins, who took the shorter route across the Isthmus. Perkins reached home on June 20, 1851. When Nathaniel arrived some months later, he was greeted with the news that the gold was gone, taken by robbers in Panama. Not everyone thought Perkins had told the truth, and the rumor mill went into production.

In 1857, Perkins returned to California with his younger brother John Calvin. What a difference a few years had made—the gold fields once peppered with independent prospectors had become industrialized, with hydraulic mining machines polluting streams and churning the gold-bearing hills into ugly moonscapes. For the last year and a half of their stay, Charles and John worked for big commercial operations like the Merced Falls Mining Company.

Back at home the war was on, and Charles enlisted in the 16th New Hampshire Volunteers. He mustered out in August 1863, and died three months later at the age of 37. John Calvin died in 1875 at the age of 38.

Like Fred Dunbar, Henry Lamprey remained on the west coast. He died in British Columbia in 1876. John Dearborn married in 1867, his wife died in 1868, and he died the following year at the age of 49. Morrill Lamprey came home, got married, and lived quietly, paying for a substitute soldier in December 1864. Nathaniel Johnson turned to farming and civic duties, and owned a sloop with Edwin Hobbs and Charles Lamprey. Lamprey was mentioned in a 1938 Portsmouth Herald article as one of the “famous forty-niners.”

A Portsmouth first

On November 26, 1849, the four-year-old, Kittery-built barque Martha sailed down the Piscataqua, the first Portsmouth ship to carry passengers to California. Onboard with Captain Joseph Grace and 14 crew members were 64 passengers who were “all badly, very badly afflicted with yellow fever.” Their ship proved to be a “poor sailer on the wind, and made a very long passage.” Indeed. The Martha beat the Ark’s time by only two days, arriving in San Francisco on June 18, 1850. Grace sold the ship in California and was back home within a year.

The Martha’s lone Hamptoner was Nathaniel Johnson’s cousin, mariner Edwin Johnson Hobbs. At some point after his arrival he joined his cousin in the gold fields, and they sailed home together in 1851. Hobbs spent the rest of the 1850s sailing the world on merchant vessels, sending letters home from exotic ports like Hong Kong and Rangoon. Back at home, he kept the lighthouses at Boon Island and the Isles of Shoals. He died in 1905.

A Hampton first

The first and only Hampton vessel to ship a load of Argonauts was the 130-ton schooner Harriet Neal, built by Captain John Johnson at his Taylor River shipyard and named for his niece. The ship had sailed to the Mediterranean, West Indies, and Texas, and in March 1849 carried the men of the Massasoit Overland Mining Company from Boston to the port of Chagres, en route to the California gold fields.

One of the Harriet Neal’s sailors was 19-year-old John Perkins, the brother of Caroline Perkins Joyce. Stricken with the gold fever, he jumped ship at Chagres and went to San Francisco, where he visited his sister and her family, singing old songs of the sea to his niece.

John’s story ends happily, as it was said that he worked the California gold mines “to the surprise, and, as it proved, the financial betterment of his family.” For most of Hampton’s Argonauts, however, it seems they brought home more experience than gold.

History Matters is a monthly column devoted to the history of Hampton and Hampton Beach. Cheryl Lassiter is the author of “The Mark of Goody Cole: a tragic and true tale of witchcraft persecution from the history of early America” (2014). Her website is www.lassitergang.com.

Read more details about Hampton's gold-seeking argonauts here