Exoneration For “Goody” Cole

How Town of Hampton Voted to Free Her Memory

From Charges of Witchcraft and Sorcery

The Portsmouth Herald, Thursday, August 25, 1938

[A Portsmouth Herald photo]

It seems a far cry from the lively scenes at Hampton Beach, New Hampshire’s beautiful summer resort, to the days of witchcraft, but these days have been recalled by the recent efforts of the recently formed “Society In Hampton Beach For The Apprehension of Those Falsely Accusing Eunice Goody Cole of Having Familiarity With The Devil,” and the resulting action of the voters of the town of Hampton in restoring to her rightful place as a citizen “Goody” Cole, who was imprisoned for witchcraft in 1656.

The warrant of the Hampton town meeting contained one of the strangest articles that has ever appeared in a call for a New England town meeting. Article 16, which became a part of the 1938 warrant through the efforts of “The Society in Hampton Beach For the Apprehension of Those Falsely Accusing Eunice (Goody) Cole of Having Familiarity With the Devil called for the restoration of Goody Cole to her rightful place as a citizen and when over 300 of the good people of the historic town of Hampton gathered at the town hall to decide upon the conduct of the town’s affairs for the coming year, Article 16 was passed without, opposition.

With its adoption Hampton became the first community to attempt officially to clear the stain of persecution for witchcraft and sorcery from its records.

The complete resolution was as follows:

“Resolved: that we, the citizens of the town of Hampton in town meeting assembled, do hereby declare that we believe Eunice (Goody) Cole was unjustly accused of witchcraft and of familiarity with the devil in the 17th century, and we do hereby restore Eunice Cole her rightful place as a citizen of the town of Hampton.

“Be it further resolved: that at such times as the selectmen shall select during the Tercentenary of the Town of Hampton, appropriate and fitting ceremonies shall be held to carry out the purpose of this resolution by publicly burning certified copies of all the official documents relating to the false accusation against Eunice (“Goody”) Cole, and that the ashes of the burned documents, together with soil from the reputed last resting place and from the site of the home of Eunice (“Goody”) Cole be gathered in an urn and reverently placed in the ground at such place in the town of Hampton as the selectmen shall designate.”

The question was put before the meeting by the venerable and beloved pastor of the 200-year-old historic Hampton Church, Rev. Herbert Walker, and he was heartily, supported by the youthful Judge John W. Perkins, who presides over the Hampton, municipal court, and who was eager to see removed from the records of the town the stain of unwarranted persecution which occurred in a Hampton court 300 long years ago.

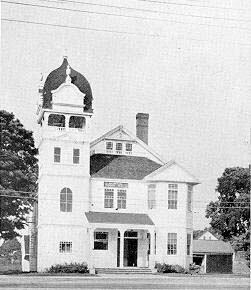

[Photo right:] HAMPTON TOWN HALL: It was here that the town folk of Hampton voted to “exonerate” Eunice “Goody” Cole of witchcraft charges.

While there was no opposition to the rehabilitation of “Goody” Cole, Arnold Dodge Philbrick, Haverhill, Mass., banker, and the thirteenth lineal descendant of Thomas Philbrick, one of “Goody’s” accusers, asked by letter that no reflection be cast on his ancestor.

He wrote, “I do not want to register my opposition to any action that would in any way discredit those who were concerned in the persecution. They acted in good faith and in accord with a belief that was well nigh universal at that time.” It is understood that it was the 17th century Philbrick who charged “Goody” with bewitching his “Cattell” (Cattle).

Secretary James W. Tucker of the Hampton Beach Chamber of Commerce motioned for acceptance of the resolution restoring citizenship to “Goody” Cole and retracting witchcraft accusations.

“This is not a publicity stunt,” Secretary Tucker said, “The rehabilitation of ‘Goody’ Cole is an act of simple justice. It is not too late to wipe the stain of witchcraft from the town records.”

Mrs. Margaret Wingate, high in the ranks of women’s clubs in New Hampshire, seconded the motion “as a representative of the female species.”

There was great applause among the citizens of the New Hampshire seacoast town when it was announced that the vote was unanimous and immediately the great bell in the belfry of the Congregational church, cast by none other than Paul Revere himself, rang out the glad tidings, spreading throughout the countryside the news that “Goody” Cole had at last been vindicated, and that the present residents of Hampton need no longer be ashamed of the acts of their stern and superstitious ancestors.

And now as to the story of “Goody” Cole. She occupies a prominent place in the history of Hampton and the history of Massachusetts Bay Province.

The noted poet, John Greenleaf Whittier, made her an important character in his poem, “The Wreck of the Rivermouth.” Imprisoned in. Boston in 1656 “Goody” Cole was released ten years later when the town balked at paying for her keep. She returned to Hampton and was shunned and jeered at by the townspeople. She was again arrested in 1680 charged with bewitching children. She was freed but the jury found “just grounds of grave suspicion.”

Shortly afterward she died and even in death got no peace as indignities were heaped upon her body.

The story of “Goody” Cole is perhaps best given in the letter written by Judge Perkins to the selectmen of the town in making the application in behalf of the “Society in Hampton Beach for the Apprehension of Those Falsely Accusing Eunice (Goody) Cole of Having Familiarity With the Devil.” The letter sought to have placed in the town warrant the article which later was adopted at the town meeting. In this communication it is stated at the opening that the society honors and venerates the founders and their children for their many virtues and believes that the delusions which caused some of them to take misguided action against Eunice Cole were brought about by the mad, fanatical aberration then prevalent in the minds of millions of Europeans.

The letter continues:

“Eunice ‘Goody’ Cole was brought into the court of the province in 1656 and found guilty of being a witch. She was sentenced to be flogged and then to be imprisoned during her natural life, or until released by the court.

“She was jailed in Boston and apparently forgotten until the Hampton officials were called upon to pay her board. The townspeople, unwilling to continue longer the expense involved in her incarceration, permitted the prison officials to allow her departure. Almost ten years after her trial she returned to Hampton, feeble and aged. Although the town fathers saw to it that she had enough subsistence to sustain life, and a place to live, the next 14 or 15 years of her existence were but a continuation of the unhappiness which had always been her lot. She was mocked and hooted whenever she made her few appearances on the streets of the settlement. Hate and aversion were plainly marked in the looks the elders gave her.

“Deprived of every kindly form of human intercourse, her life throughout these latter years was so bleak and desperate that we who live among the comforts of a later generation can scarcely conceive of the treatment accorded her. When the most natural instincts of the human mind caused her to seek relief in human companionship immediately the hue and cry of witchcraft was again raised. Although she was now 75 years old she was again taken into custody, charged with bewitching a young girl to whom it was alleged she had appeared in various forms of animal life — as a dog, a cat and an eagle. The jury decided there was “Just grounds for grave suspicion.”

“Infirm, aged and begrudged even the little that was given her, she heard no words of sympathy, nor experienced any kindly acts. Still insulted and jeered, she trod a daily path of torture and hopeless existence. At last death put an end to her life of suffering. But even death did not prevent the last of the indignities. They were now heaped upon her spent and lifeless frame. A frenzied mob, without right or justification carried her stark body roughly, brutally and hastily to a shallow roadside trench where they buried it. Then in the cruel and superstitious manner of the times the body was impaled with a` stake to the top of which was affixed a horseshoe. Thus was it made certain that Eunice Cole could not rise again and revisit her usual haunts, and by means of the horseshoe the community was assured the devil would not be able to take her body away.”

Outside of the persecution of “Goody” Cole there does not appear to have been much witchcraft in New Hampshire. When the great drive against witchcraft was underway at Salem, Mass., there was comparatively little witch-baiting in the Granite State.

Records show another case of witchcraft in 1680. The place is not certain, but from the names of some concerned in it, probably it was in Hampton. The evidence was given in a court held in that town. A child about one year old, belonging to John Godfre died. It was suspected that it had been bewitched by Rachael, wife of John Fuller. July 13, a jury of inquest sat on the case. The foreman was Henry Roby, early at Exeter, afterwards in Hampton. On the jury were Henry Dearborn, Abraham Drake and others of Hampton. The verdict was that, the child had been murdered by witchcraft. One reason given was, what they saw by the dead body, and another, was, in what they saw and heard from the party suspected.

[A Portsmouth Herald photo]

The next day, July 14, John Fuller entered into bonds of 100 pounds for the appearance of Rachael, his wife at court, to answer to the charge of witchcraft. According to the testimony in the case Rachel Fuller visited Mr. Godfre’s home, where the child was sick, took hold of the child, said it would be well, went out of doors, looked toward the house and beat her arms together; also, that, she told one that a doctor was pulled out of bed with an enchanted bridle and that it was intended to lead him a jaunt; also that she had been seen out, scrabbling on her hands and knees. There is no record of any decision by the court, and it is believed that was probably dropped.

Portsmouth and vicinity were also troubled with witchcraft in early times. The first date was in 1653, just 30 years, after the town was settled. Jane Walford stated to John Juddington that her husband called her an old witch, and that when she came where his cattle were he would bide her begone as she bewitched them. Three years passed, and so far as it is known cattle and human beings had not great annoyance from the power of witches, but in 1656 the aforesaid Jane Walford seemed to be making special trouble. The scene was at Little Harbor, where probably Jane resided. It was on Mar. 30, in the evening, that Mrs. Susanna Trimmings was walking alone, when Jane Walford came to her and asked her to lend her a pound of cotton. Mrs. Trimmings declined, Jane told her she would have trouble, and left her. Susanna was immediately struck with a “clap of fire,” and she “saw something vanish in the shape of a cat.” She went home, could not speak at first, even hardly breathe. Finally she told her husband, Oliver, that her back where she was struck was a flame of fire; her limbs were numb, and she said, “Jane Walford will kill me.”

Mrs. Trimmings made oath to the particulars before the magistrates in the case. In June others gave testimony, among them Nicholas Rowe, who said that Jane Walford, after she was accused as above, came to him in bed in the evening, put her hand on his breast and then left. He could not speak and was in great pain till the next day. She repeated (as he alleged) the operation a week later. Jane was by the Court held in bonds. The record in June was, that she was bound to the next Court. The outcome of the case is not on record but it is believed that the case was dropped. Jane lived on and some called her a witch. But she finally thought to silence such accusations. In March, 1669 Robert Cutch having called her a witch, she brought an action of slander and the Court gave the verdict in her favor with five pounds lawful money as damages, and costs of Court.

Trouble arose in Portsmouth on June 11, 1682. It was on the Island (now Newcastle) George Walton lived not far away from the bridge, on what is now, the right hand street leading to the business part of the town. There was no street there then, and there is no house where Walton then lived.

A gate was wrung off the hinges and showers of stone thrown at the house. Stones from within were thrown out through the windows, breaking the glass. Stones hit, persons, but effecting no more than a soft touch. Stones were picked up, some of them as hot as if coming from a fire. Some were placed on a table, but they commenced flying about. No one was seen throwing stones. Some articles went up chimneys, then down again, and then out of the window. Similar operations, and more than can be put down here, continued several days. It wouldn’t do to neglect to note that a cheese flew out of the press and ambled over the floor, and cocks of hay went up and hung on trees!

.There are some who will want an explanation of these queer happenings, but all a historian is supposed to give is facts and not sit in judgment on them. There were people at the time who swore that the above actions were facts, and so they are recorded as such here. It might not be out of place to state that a disordered imagination has sometimes created strange fancies.

One hundred years later witchcraft was believed to have existed in this city. It was at the time of the Revolutionary war. Clement March was keeper of the Portsmouth Almshouse, and Molly Bridget was an inmate; she was called a witch. In 1762 there was trouble with the pigs and it was said they were bewitched; the tips of their ears and tails were cut off as a remedy. It was a tradition that they must be burned, but they could not be found. Chips were collected, supposing the tips were among them; as they were put into the fire, Molly appeared frenzied, went to her room and died immediately.