This World-Famous Sculptor Flourished

During Little Boar’s Head’s ‘Golden Age’

{1887 — 1966}

Hampton Union, Tuesday, September 22, 1987

By Vern Colby, Contributing Writer

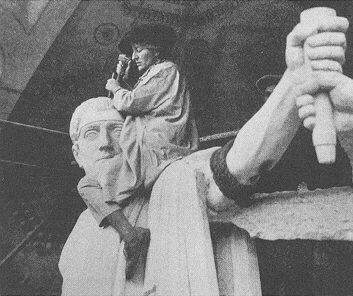

[Photograph not in original article.

From “Yesterday Is Tomorrow (A Personal History)”

by Malvina Hoffman – 1965]

NORTH HAMPTON — When sculptor Malvina Hoffman died on a summer’s Sunday morning in 1966, the New York papers made much of her life and her passing.

Then, on Monday, July 11, The New York Times started its page-one story of praise with an attractive picture of a woman growing old with grace. But it must have been taken at least a decade earlier, for she was 81 when her time came. In the first sentence, that foremost newspaper calls her “One of the few women to reach first rank as a sculptor . . . .”

The next Saturday in its magazine section, the New York Post filled a page paying tribute to her life. For those in the Seacoast, one sentence, in the midst of many, stands out even today: “Her childhood summers were spent happily at Little Boar’s Head (North Hampton), on the New Hampshire coast.”

Those are the reasons to write of her today, 21 years after she left this life. Her greatness was acknowledged during her life. She had a wide circle of friends. Among them were the movers and shakers in the arts, medicine, education and finance She was a child of our own shores. As maturity deepened her, she continued to spend time here.

Malvina Hoffman was of the golden group that made this shoreline a special place, from about 1840 until a little more than a century later. During that time, people of accomplishment, character and resources spent summers here and in Rye.

A Lively Writer

Malvina Hoffman was a writer with a lively style. Her major books, “Yesterday is Tomorrow — A Personal History,” and “Heads and Tales,” an account of her five-year journey throughout the world to prepare sculptures of the world’s races. They were commissioned by the trustees of Chicago’s Field Museum for their Hall of Man. The books give a good accounting of her life, gifts and spirit.

Selected chapters from the way it was in North Hampton by Stillman and Helen Hobbs describe what life was like for the golden group.

Principally, this writer’s debt is to Mr. and Mrs. Robert A. Southworth for materials provided and the richness of their personal remembrances. “Remember,” said Bob Southworth, “her name is pronounced like Mal-vee-na, and her nickname was ‘Mallie.'”

Mallie, born in New York City in June 1885, arrived at the North Hampton railroad station two weeks later, safety pinned, I supposed, to a pillow. It would have been a carriage that brought her to Bachelder’s Hotel in high style, and likely with dramatic flourish. Southworth’s mother, born of the hotel-owning Batchelder family, was close to contemporary with the sculptures-to-be.

It is safe to assume that flourishes and joyful noises greeted Malvina’s arrival at Bachelder’s, for her father was respected and popular. He’d been a prodigy on the piano and the organ. Born in Manchester, England, he came to America in 1847 at 16. That year, he played as soloist for the New York Philharmonic Society. Three years later, he was engaged by P.T. Barnum to play piano for Jenny Lind’s first American tour. Since the Swedish Nightingale was a smashing success, this was a grand break for Richard Hoffman. He became soloist for the New York Philharmonic when he was 22, and held that post for 30 years. During the Civil War, he organized a series of concerts raising money for wounded soldiers.

On her mother’s side — Lamsons, Marshalls — was a founding family of Ipswich, Mass.: inventors, doctors, missionaries, ministers and business people.

Rich social life

A decade or so before Malvina’s first journey to Little Boar’s Head, the Hoffmans began to summer there. Her father soon became organist and choir director at St. Andrews by-the-Sea at Rye Beach, kept musical activities busy at Batchelder’s and on Sunday evenings at the hotel, played in the parlor.

People drove for miles to listen to these, and many, I suppose, listened on the grounds. With all of this as background, “Mallie” certainly was a center of attraction, apparently, enjoying every minute of it in an unspoiled way. Professor Nash, classical languages, Harvard, played an essential role in starting her toward sculpture by guiding her as a child in the carvings of Little Boar’s Head driftwood.

This active girl of lively curiosity became a foremost sculptor of her generation. She was a pupil of the master, Rodin. She did serious study in anatomy. She developed practical engineering knowledge, for sculptures of significant weight and mass demand inner support structures and physical balance.

All this dedicated study and practice led to commissions for the project with Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History to develop over 100 sculptures representing The Races of Mankind.

She was in her 40s when she received the Field Museum wire, “Have proposition to make, do you care to consider it? Racial types to be modelled while travelling around the world.”

Documenting humanity

That museum is strong in anthropological presentations. They had an anxiety for the project. As modern world travel and expansion of populations continued, the museum feared that the purity of racial types once protected by isolation would be adulterated. Her work, considered of major importance, was displayed as a complete collection for many years in the Hall of Man. From that work’s finish, almost to the year of her death, she had more commissions offered than she could accept.

Her school of sculpture was realism, no abstract sculpture for her. A former student of anthropology visited the Hall of Man and say this of her work, “I went to the Chicago museum to study her work with a scientific attitude, but the figures were so artfully made, and seemed so close to exploding with life’s vitality, that I was caught completely in admiration of her art.”

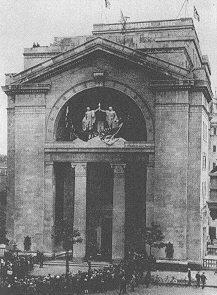

Her works were displayed in many museums and private collections, once at the New York World’s Fair in 1938, at the American War Memorial Building in France, and in London [see photos at end of article].

Her capacity for friendships was democratic and limitless — from the famous to farmfolk. Sometimes at her homes and studios in New York and Paris, she would give large and enjoyable parties. A party during World War II in New York was for merchant seamen from 32 nations fighting Nazi Germany. New Year’s greetings from these men to their homelands were recorded and broadcast overseas.

There are people here who remember her when they were young and she was middle-aged. All speak of her directness.

“When she spoke to me, it was a quick, but interested, ‘Good morning,’ for she was busy, and her tones were good-natured, and the directness of her manner made you feel she cared.”

Mrs. Southworth speaks of her winning ways with children, for the Southworths lived in New York City for a number of years, and there was a strong friendship.

“Once, Malvina arrived at our apartment when the boys were sick and a vaporizer was working. Soon as possible, she was in with them, talking animatedly, playing with them; tin-soldier games, giving them her complete attention. Sometimes her directness was almost disconcerting, but the boys responded to this directly focused interest.”

Recovering the Squalus

Her aptitudes and experience in practical engineering sometimes found unusual outlets. Bob Southworth says, “She was with us at Little Boar’s Head, when the submarine [USS] Squalus sank, and as efforts were being devised to raise her from the depths without having her slip back, Malvina was actively interested in any help she could give. She was in lengthy contact with Admiral Cole at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard about techniques that might be effective.

In the 1940s, Malvina Hoffman connected two of the old fish houses at North Hampton for a studio by the sea. This was the initial move to change them into the admirable and desirable seaside retreats that they are today.

She loved these shores. Her artist’s stamp of approval for the beauty of New Hampshire’s coast cannot help but enhance our own appreciation.

[Photograph from Head and Tales in Many Lands, by Malvina Hoffman.]

[Photograph from Head and Tales in Many Lands, by Malvina Hoffman.]

[Photograph from Head and Tales in Many Lands, by Malvina Hoffman.]