History Buff Honors WWII Servicewoman

By Susan Morse

Hampton Union, Friday, February 20, 2004

[Photo by Susan Morse]

HAMPTON – Lane Memorial Library volunteer John Holman is a local history buff who has also been around long enough to have made friends with those who made history.

One of those friends is Ansell Palmer of Hampton, brother of Lt. Rita Palmer, the World War II Army nurse who was a prisoner of war for three years following the American surrender at Bataan.

Hampton residents may recall her celebrated homecoming in town following the American liberation of the Philippines in 1945.

A special car was sent to get Palmer at Logan Airport in Boston and bring her home, where she was feted with speeches in Marelli Square, brother Ansell Palmer related Wednesday. She was reportedly greeted by 1,000 well-wishers.

Rita Palmer passed away Feb. 14, 2002, and is buried in the family lot in the High Street Cemetery.

On Wednesday, Holman honored the second anniversary of Rita Palmer’s passing in a tribute given at the Lane Memorial Library. He gave his friend Ansell a well-researched booklet of newspaper articles, photographs and other memorabilia on Lt. Rita Palmer, who was among the few World War II female veterans to receive the Purple Heart.

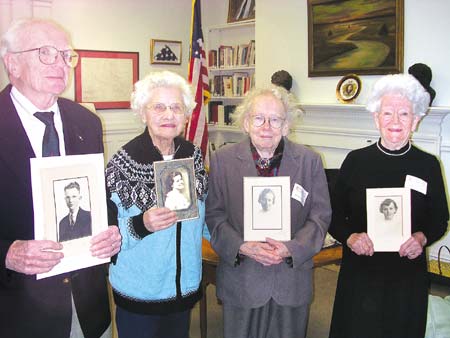

The ceremony included four of Palmer’s classmates from Hampton Academy’s Class of 1936 – Alta Gillmore Kimball, Margaret Noyes Lovett, Eleanor Palmer Dennett Young and Francis Nownes.

“She was a lot of fun,” said Young, who was also a cousin. “She was very caring.”

Young remembers going to the Colonial Theater, where Eagle Photo is now located, in Portsmouth, to see a movie. She can’t remember the name of the movie but nurses were featured.

“She said, ‘That’s what I want to do,'” remembered Young.

“She was a darn good-looking woman,” said Frank Nownes.

Ansell Palmer said he missed his sister’s homecoming because he was still serving in the Navy in the Pacific. He did get to see her after her release from the camp, he said, in Oahu, on her birthday, Feb. 23, 1945.

A picture of brother and sister is in Peter Randall’s book, “Hampton, A Century of Town and Beach, 1888-1988.” Ansell Palmer is behind the wheel of a Model T racing car he restored.

Palmer’s story, and that of the other 71 nurses taken prisoner in the Philippines, is featured in the 1999 book, “We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of American Nurses Trapped On Bataan by the Japanese,” by Elizabeth Norman.

Palmer joined the U.S. Army Nurses Corps in 1941 and served in a field hospital in Bataan and Corregidor until the American surrender there, in which she was wounded and taken prisoner. She spent three years interned in Manila at Santa Tomas Jesuit University.

In May 1945, Palmer told her story to the Hampton Union.

According to her account, the first two years in the camp, “went fairly pleasant,” she said.

Bedbugs were common and soap was a precious commodity. Food was supplemented by native markets and gardens.

Nurses worked four hours a day in the small prison hospital. For a reward, they were sometimes allowed to buy soap or cigarettes.

After work, they took classes taught by professors who were in the internment camp and by priests from the University of the Philippines. Palmer earned the equivalent to a year of college education.

There were baseball games and a stage show on Saturdays. On Christmas 1943, a group of internees presented the “Messiah.”

“Every occasion for a celebration was grasped,” Palmer said. “The birthdays and anniversaries of the members of each one’s family far away in the United States or some country were duly feted with a special tablecloth and a cake baked in an oven.” The “ovens” were closer to inverted flower pots.

Cloth was purchased from the Japanese to make clothing. Women knitted and crocheted underwear and socks using bamboo knitting needles.

The only Red Cross shipment arrived in December 1943. Many got sick from the chocolate in the packages.

In 1944, everything changed, Palmer said. Air raids meant the Americans were drawing closer. They got news of the war via word of mouth, Palmer related, but didn’t know until later it came from one man in camp who had secretly set up a radio.

Rice became the only food and was rationed. Beriberi began to appear. Some people ate cats, Palmer said, and a large flock of pigeons that had nested in the eaves gradually disappeared.

Palmer was in the hospital with dysentery when the Americans arrived in tanks. She went to the window to watch American soldiers pour into the camp. One gave her the first chocolate bar she had eaten in two years.

Holman’s tribute of the anniversary of Palmer’s passing coincides 61 years after the Kiwanis Club of Hampton dedicated a service flag to the 198 men and women of Hampton, North Hampton and Hampton Falls who were then serving in the armed forces and to the memory of Lincoln H. Akerman, killed in the South Pacific in November 1942.