By Alton Hall Blackington

New Hampshire Profiles

pp. 22-23, 44, 45 (April 1961)

built after Satan set fire to the original building.

[Photo by Elizabeth Plumer]

Two events in the life of General Jonathon Moulton of Hampton, New Hampshire, have been seized upon by various writers as bits of legendary history that should not be forgotten.

The first concerns Moulton’s encounter with the Devil and his agreement to sell his soul for a pile of gold. The second involves the ghost of his first wife Abigail, whose icy fingers clutched the rings and bracelets from the hand and arms of Jonathon’s second wife, Sarah. This latter event was preserved for all time by John Greenleaf Whittier in his poem, “The New Wife and the Old.”

Several years ago, anxious to get whatever facts there were about these New Hampshire legends, we drove down US Route 1 and, just before we reached the village of Hampton proper, turned sharply left into a private drive that led through old-fashioned gardens to a huge, high, two-story yellow house with three black-topped chimneys.

We were greeted by the owner, tall, pleasant-faced, gray-haired Harland Little, who laid aside his garden fork and led us into the spacious kitchen where his two sisters, Catherine and Sarah Little, were preparing lunch. Two fat iron kettles were steaming on the back of the old-fashioned cook stove set in front of a yawning fireplace. The room smelled of herbs and fresh baked gingerbread.

Pointing to the huge hearth with its crane supporting pans and copper dishes, I asked, “Is this where the Devil is supposed to have dumped the gold coins?”

The sisters shook their heads, and Harland said, “Well, you know, Blackie, the original Moulton place which sat down the road a piece, burned down. General Moulton replaced it with this house in 1769, and Ralph Adams Cram tells that the ell of this house used be a separate building. Just under that window you can see the hand-cut clapboards that were put on with handmade nails.” He went to fetch me one of the original nails, square and rusted.

“We’ve been told,” Harland added “that some of the original bricks in the first house were saved and probably were used to finish this fireplace.” Miss Sarah Little handed me a moist, warm chunk of gingerbread, and her sister Catherine poured the rich black coffee.

{Photo not in original article.}

[Photo courtesy of Atty. H. Alfred Casassa – 2005]

Harland continued, “All we know about that fire is the piece that was printed in the Boston Chronicle of March 20th, 1769. It says, ‘Last Wednesday morning, about four o’clock, the large mansion of Col. Jonathon Moulton of Hampton, together with two stores contiguous, was wholly consumed by fire. This melancholy accident, it is supposed was occasioned by a beam taking fire under the hearth in his parlor. The flames had got to so great a height before the discovery, that it was with great difficulty the family escaped with their lives. Col. Moulton saved no other clothing than a cloak, and a gentleman who happened to be lodging there was obliged to jump from a chamber window. There were between 15 and 20 souls in the house at the time, who, through the good providence of God, were all saved unhurt.

“‘All of the furniture, which was very good and valuable, was consumed, but the shop goods, books, bonds, notes and other papers which were in the stores were happily saved. The loss is estimated at 3,000 pounds sterling. The burning of Hampton House, on Town Meeting day, is the most destructive fire in the town’s history.'”

Harland Little helped himself to a cup of coffee, then continued. “General Moulton, observed by his neighbors as he poked through the smoking timbers of his mansion, said, ‘I hoped I would find some of the money I had here, but there’s nothing left but ashes.'” Mr. Little handed me a copy of Dow’s History of Hampton, which on page 216 states, “Col. Jonathon Moulton was allowed five pounds . . . for money burnt with his house.”

Some of Moulton’s neighbors believed that he had a great deal of hard money hidden in his strong-boxes, and one story led to another, until some wag came up with the tale that Jonathon had been in league with the Devil, and had “sold his soul for a pile of gold coins.”

How else could he have purchased so much land, had a retinue of servants and slaves, and built stores, sawmills, and owned shares in sailing vessels?

The story was given further credence by Samuel Adams Drake in 1881, when he published his second edition of The Heart of the White Mountains.

He wrote that one dark stormy evening, when the General was sitting alone by his fireplace, a shower of sparks came spattering down the chimney, out of which stepped a figure dressed in black velvet. “Your servant, General,” quoth the stranger, picking up a live coal between his bare fingers and consulting his watch. “We must make haste, for I am expected at the Governor’s house in a quarter of an hour.”

Knowing that Portsmouth was five long leagues away, and this strange visitor planned on getting there in fifteen minutes, the General stammered, “Then, you must be the . . . .”

“Tut! Tut! What’s in a name?” asked the stranger. “Is it a bargain?”

At the talismanic word “bargain” the General pricked up his ears. “What proof have I that you can perform what you promise?”

The Devil ran his fingers through his hair and a shower of guineas fell to the floor. The General stooped to pick up one of the coins but dropped it quickly. It was red hot!

“Try again,” said His Satanic Majesty. The General reached timidly for another piece of gold, and this coin was cool and rang true. He gathered up a handful of guineas. “Are you satisfied?”

“Completely, Your Majesty.”

“Well, now that you are convinced I am able to make you the richest man in the province, listen carefully. In consideration of your agreement, duly signed and sealed, to deliver your soul” — and he drew a parchment from his pocket — “I agree, on my part, on the first day of each month, to fill your boots with gold coins like these before you. But, mark me well, if you try any tricks, you will repent it.”

Satan opened the scroll, smoothed out the creases, dipped his pen in an inkhorn at his girdle, and pointing to the parchment said, “Sign!”

Glancing at the names on paper before him, the General added his signature, mumbling, “At least I shall be in good company.”

“Good!” said Satan, tucking the parchment into his breast pocket. “Be sure you keep faith!” In another second he had vanished up the chimney.

The Devil performed his part of the bargain to the letter. On the first of every month the boots that the General had hung on the fireplace crane the night before were found in the morning crammed full of gold guineas.

But the General wasn’t satisfied. The more gold he got, the more he wanted, and he made plans to cheat the Devil, if he could.

Grabbing the boots and his axe, he dashed to the chopping block back of the house, and with a sharp blow severed the toes from the boots. “Now,” he snickered to himself, “let’s see what happens next.”

A few nights later, Satan arrived and started the coins rattling down the chimney. The General chuckled with glee as they landed in his boots, rolled out through the open toes, and began to pile up on the base of the hearth.

The Devil, sensing something was wrong, looked into the situation. When he saw what had happened, he flew into a rage. He tore the boots from the crane, and, as more coins cascaded to the hearth, they were now white hot! One of them rolled into a wide crack between the floor boards and started the fire which in a matter of minutes destroyed “Hampton House” and everything in it.

When I finished reading this account there in the Littles’ kitchen, I handed the book back to Harland, who said, “Did you happen to notice that Author Drake never once used the name of Moulton? He calls the Devil’s victim ‘General Hampton.’ But when Drake brought out his splendid stories, New England Legends and Folk Lore, the man who tried to cheat the Devil is correctly named as Jonathon Moulton.”

I said, “What’s all this talk about the first wife’s ghost snatching the rings off the second wife’s fingers? When and where did that happen?”

and snatched the rings and bracelets from Sarah’s

hands, in the Moulton house in Hampton.

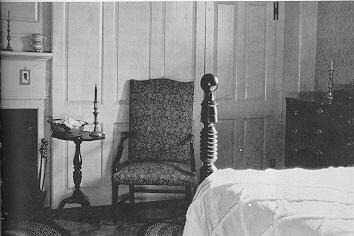

Harland rose and beckoned me to follow him out through the hallway and up the broad staircase to the second floor. Opening a door that led into a delightful room with two windows and a fireplace, he said “This was the Moulton’s best guest chamber. They called it the Green Room, and over here” — and he opened another door — “is the Best Blue Room. It was in here where the jewels were grabbed by the ghost.”

As I appeared to be somewhat perplexed, Harland explained. “You see, Blackie, the General had got tired of his first wife, Abigail, and when she was stricken with a strange illness and began to waste away, Jonathon sent for her good friend Sarah Emery to come to Hampton House and take care of her. While Sarah was looking after the needs of Abigail, Jonathon spent his time looking after Sarah; and soon the affair became a public scandal.

“Jonathon had given his first wife many costly rings and bracelets, and one night, when he was in his cups, he strode into her chamber, this very room, and wrenched the rings from Abigail’s emaciated fingers.”

“Yes,” said Catherine Little, who had arrived with a volume of the Moulton Annals, “and he gave those jewels to Sarah Emery, and she wore them whenever she went out in public. Think of it! And his wife Abigail not yet dead!”

Harland leafed through the Moulton Annals and found what he was looking for. “Here it is. Abigail Smith Moulton died on September twenty-first, 1775, and less than a year later, in 1776, Jonathon Moulton married her friend.”

“Well, where does the ghost come in?” I said.

“Oh,” said one of the sisters, “while Jonathon was snoring his head off, in a drunken stupor downstairs, on their wedding night, his new wife Sarah was up here in the Blue Room crying her eyes out. Suddenly she heard footsteps coming up the stairs, and then she saw the ghostly hands of Abigail coming straight at her. She felt their icy touch as they snatched away her rings and bracelets. Neither the jewels nor Abigail’s ghost were ever seen again. And it happened right here in the Blue Room.”

“And that’s the story,” Harland added, “that John Greenleaf Whittier wove into his romantic poem, “The New Wife and the Old.”

When General Moulton died on September 18th, 1787, he was given an impressive funeral attended by officials of the state and government. He was laid to rest on his own land; today, nobody knows exactly where. The rumor still persists that the General had been friendly with a chemist who boasted he could mix a poison so subtle it could not be discovered by smell, taste, or color. The General had cheated this chemist in a business deal and had won his enmity. The chemist invited General Moulton for a sumptuous dinner; shortly afterward the General was stricken with a violent illness and died the next day.

The second Mrs. Moulton, Sarah Emery, lived on in Hampton House till she married The Reverend Benjamin Thurston and moved away. The house was then taken over by Mr. Whipple, a lawyer, who arrived in grand style with coach and four, outriders, and colored servants. But the servants and slaves, hearing ghostly tramping in the upstairs corridors, fled the house, and the Whipples had to send for two ministers to “lay the ghosts.” With some effort the clergymen cornered the ghosts in a cellar closet, which they bolted up with heavy planks.

When George Washington passed through the village, he stopped at Hampton House and had a cup of tea there to honor General Moulton.

For many years the old Moulton mansion stood deserted, unpainted, by the side of the road. Everybody in Hampton referred to it as “the haunted house.”

In 1920 Harland Little of Salem and his two sisters saw the place and resolved to restore it to its former glory. It was barren of furniture, and the twelve fireplaces were choked with leaves and dust. First they moved the house, separating an ell, and hauling the two halves up to the knoll where it now stands. New foundations were built, the weather-beaten boards were painted a cheerful yellow, and the grounds were landscaped.

Harland Little passed away last year, and the sisters are doing their best to keep the house in proper shape.

Talking with them a few days ago, I asked if they ever hear or see anything of the ghosts that have haunted the place.

“Well,” said Catherine, “we don’t see any ghostly figures, but we do hear thumping and knocking sounds in the chambers upstairs.”