By Chris Herbert

New Hampshire Business Review, October 27, 1995, p.1

Reprinted with permission of the New Hampshire Business Review

In the financial press, it’s considered a truism that American companies have transformed themselves during the past 10 years into lean, mean productivity machines ready to win in a newly competitive world.

The press should check in with Dick Lilly. Call it a reality check.

“Ninety percent of the time a job is on the manufacturing floor, nothing is happening to it. It’s idle,” states Lilly, founder of Lilly Software Associates in Hampton.

Lilly knows what he’s talking about. His company has one of the hottest suites of software products designed to make small to medium manufacturers more efficient.

Called Visual Manufacturing, the Windows-based software allows these manufacturers to be precisely on top of the critical information required to guarantee on-time delivery of product. Visual Manufacturing takes a particular job from its estimating stage in engineering, and releases it as work to the shop, tracking its cost and material usage step-by-step, and operation-by-operation until shipment.

It also includes financial modules for general ledger, accounts receivable and payable as well as payroll and human resources.

Installed properly, Visual Manufacturing can drop job lead times from weeks to days. “In reality, there are few jobs in manufacturing that should take a week to do,” Lilly argues.

Although Lilly Software only shipped its first software in December of 1992, it shipped $1.4 million in ’93, $4 million in ’94 and is on track to ship $9-$10 million this year. Lilly figures he can ship about $15 million in ’96 and as much as $25 million in ’97.

“We can’t continue to double every year, but in theory our market is almost unlimited because this software concept can be expanded into many marketplaces,” he says.

Visual Manufacturing is growing rapidly, in part, because it’s only in the past couple of years, with processors like the Pentium, “that we’ve had the hardware available capable of doing the job,” explains Lilly.

Visual Manufacturing software is specifically designed to take advantage of client/server, relational database and Microsoft Windows Graphical User Interface technology.

Prior to the client/server systems, and prior to Pentium-class CPUs, there were only mainframes and UNIX operating systems. “When they wanted to turn on scheduling, everyone else came to their knees, including finance. And guess who always owned the mainframe — the finance department.”

That Dick Lilly has the product makes perfect sense. This whole business originated when IBM “invented” something call Material Requirements Planning (MRP) in the early 1960s. Lilly was at IBM. “The whole mason they invented MRP was to sell IBM computers. Initially MRP just exploded parts needs.”

It may have helped sell mainframe computeers, but according to Lilly, the customers really had little idea of how to actually use such a concept effectively. And even if they did, the mainframes were about one five-hundredth the speed of the Pentium, and everything else on the computer came to a halt while MRP software was being run.

Not anymore. With the client/server setup and the powerful CPUs available today, Lilly envisions manufacturing facilities where workstations are situated at every critical manufacturing juncture. “Everybody in the company needs to be able to use it. Let the people in the shop see what happens when they put the data in.”

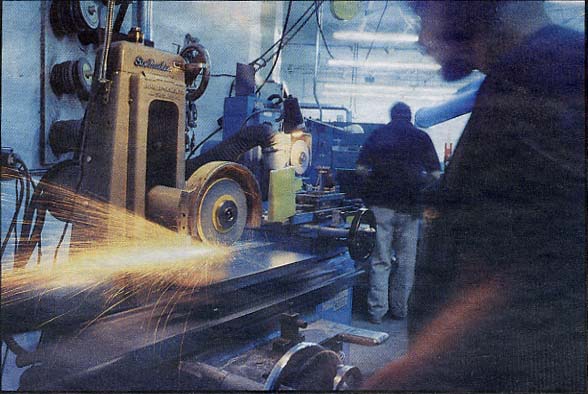

One Australian manufacturer with 14 workstations and Visual Manufacturing is a good example of what Lilly wants to happen. This company supplies custom-engineered metal components and assemblies to a diversified group of original equipments manufacturers.

Once the job is scheduled, it is then released to the manufacturing floor where materials are purchased and issued just in time. At all times, the system tracks and posts labor and costs. Using bar code entry enables everyone on the job to interface with the computer system. At every step of the process, information is posted to the job. As materials arrive they are scanned and assigned to a particular job.

At each step of the process, the floor worker scans his information into the system, capturing time, labor, machine utilization and so on. At the shipping stage, the completed job is logged out of the system and the invoice is sent out immediately.

Using Visual Manufacturing as an intelligence system, clients get an accurate picture of just where the problems really are. “We try to teach people to look for bottlenecks, then manage throughput through that bottleneck,” Lilly points out.

But Lilly is far from satisfied. Although Visual Manufacturing is hot as a product, he feels manufacturers need to be educated — to be prodded into doing things more efficiently. “MRP is 11 different things to 11 different people. American manufacturers have been using it improperly and it has jeopardized the soundness of a lot of companies,” he asserts.

One big problem is, as Lilly puts it, “The question of just who is the master scheduler.” Lilly believes that, in the small- to medium-sized companies, it has to be the company president — or whoever actually is in charge of the entire operation. It can’t be someone who is in charge of only part of a company. “The specialist will never tell who’s function it is to be master scheduler,” he states.

Too many bosses are shirking their responsibility. Lilly cites Japanese manufacturers, who he claims never had any use for MRP because they always communicated directly with suppliers.

‘”Kan Ban,’ they call it. Do what is needed today. Every morning the main manufacturer sits down with the presidents of his supply companies. Their plants are just down the street, or across town. He says, “This is what I need today, so many parts here, so many parts there. Can I get them now?’ If he can’t get everything he wants now, he adjusts accordingly. But everyone knows what’s going on. Everyday.”

Used properly, Lilly believes Visual Manufacturing is a worthy American adaptation of “Kan Ban.” With workers tied into his software (in fact many different suppliers can be tied in together) and seeing the whole process in action, not just their specialty, Lilly believes American manufacturing will begin to really be competitive. “Let everybody in the shop see what’s actually going on. Once you do that, they are going to find a better way of doing the entire job.”

To Dick Lilly, Visual Manufacturing is the tool manufacturers need to achieve the next level of efficiency.

“American Industry is not behind Japan. We’re behind our own 8-ball.”

Based on the rapid climb in Visual Manufacturing sales, it’s an 8-ball more and more companies are putting in the side pocket — for good.