In High-tech Age, Motor Skills Still Matter

By Debbie Kane

Hampton Union, Tuesday, October 7, 2008

[The following article is courtesy of the Hampton Union and Seacoast Online.]

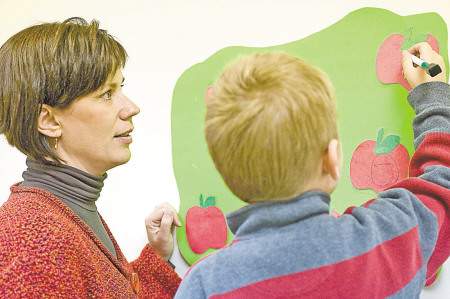

[John Carden photo]

In an era in which e-mail, instant messaging, and texting appear to be replacing pens and pencils as primary modes of communication, good handwriting seems unnecessary. Not so, say experts. The handwriting is on the wall — and it isn’t looking good.

Nearly 10 years ago, American Demographics magazine reported poor penmanship cost U.S. businesses nearly $200 million a year in lost time and revenue. In medicine, bad handwriting can have devastating consequences. According to the online Student Doctor Network, confusion over medications with similar-sounding names and spellings accounted for 15 percent of all errors reported to the United States Pharmacopeia Medication Errors Reporting Program from 1996 to 2001. Drug manufacturer Eli Lily even took out a full-page ad in a 2006 issue of The Journal of the American Medical Association asking physicians to write out prescriptions in capital letters.

“Lots of parents and teachers say that handwriting isn’t important anymore,” said Robin Ratigan, a licensed occupational therapist from Hampton Falls. “But the process of handwriting goes along with the development of ideas.”

Ratigan operates Capable Kids, LLC, a private practice in Hampton, providing therapy to children in preschool through second grade with a variety of learning and developmental difficulties.

“Research has shown that between 30 to 60 percent of a child’s day is spent doing tasks that require fine motor skills,” she said. “Imagine that you’re challenged and 30 to 60 percent of day is spent doing things hard for you. That’s a long time for teachers to say handwriting doesn’t matter.”

Children use their hands to interact with their environment and communicate what they know. They can have good motor skills but still struggle with handwriting basics. Young children progress through developmental phases and their activities — playing with blocks, dressing dolls, or cutting with scissors — support these phases and how they relate to their environment.

“Just as we go to the gym to get our muscles developed to get in better shape, children need to do certain activities so they can develop,” Ratigan said.

[John Carden photo]

If children miss those activities because they’re on a computer game, keyboard or watching television, they miss that “aware time.”

“If you’re sitting with a mouse in your hand or at a keyboard, your hands aren’t involved in the activities you need to move through these developmental phases because it takes time to develop,” she said.

Another cause for delays can be traced to toys and equipment marketed to make children “smarter.” Susan Gregory Thomas, author of “Buy, Buy Baby: How Consumer Culture Manipulates Parents and Harms Young Minds,” suggests there was never any real evidence to prove “educational” toys, shows and products provide actual benefits for young children.

“What might be called the baby genius phenomenon — the widely-held notion that infants and toddlers can be made smarter via exposure to the right products and programs — has spread throughout the toy industry,” she wrote.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has stated babies and toddlers need direct interactions with parents and caregivers for development of appropriate social, emotional and cognitive health. It also notes there is no current evidence to support that popular infant “educational” videos help infants and toddlers in an intellectual or developmental way.

Ratigan agrees. “The neurological research that was supposedly behind these products demonstrated that children up to age three who were deprived of stimulation would have problems unless they have more stimulation,” she said.

Products like Baby Einstein and Leap Frog play to parental fears that unless a child is listening to classical music or learning how to manipulate a keyboard, they’ll fall behind their peers in school.

“You learn about everything through touch — judgment, distance, force,” Ratigan said. “If you’re just clicking on a computer, you don’t understand near or far. You don’t develop that judgment.”

Baby equipment such as combined infant carriers/car seats and bouncy seats can also be problematic, Ratigan said. Because a child sits in these seats in a semi-reclined position, sometimes for long periods, this can actually interfere with his ability to develop strong core muscles. He doesn’t have the strength or energy to sit in a chair at school.

The implications can play out in preschool. Often, parents are referred to or seek out Ratigan’s services if their child is acting out at school or a teacher notices activities — such as buttoning clothing or coloring and cutting with scissors — may be difficult for the child to accomplish. Many of these children aren’t labeled learning disabled so they won’t receive occupational therapy from their schools.

“When I worked in the school system I saw kids who were struggling but didn’t have a specific disability, so they couldn’t get services in school,” Ratigan said. “I wanted to offer this service to that group of kids.”

Susan Schmettler of Hampton brought her 5½-year-old daughter Lauren to Ratigan when she was in preschool. Lauren had trouble holding utensils as well as a pencil; she had no interest in printing letters at school and was fidgety. Now in kindergarten, Lauren writes lowercase and uppercase letters and “knows what she needs to do to empty her engine” so that she can sit still in school, Schmettler said.

“Robin is a miracle worker,” she said. “She brings out the best in Lauren and really encourages her.”

Ratigan tailors therapy sessions to her clients’ needs. Generally, a child starts with gross motor activities like crawling and playing games that utilize her entire body. Children strengthen their hands using markers and pencils to write on paper tacked up on the wall; they also can use tweezers to pick up small beads or use training chopsticks as well as gluing and cutting with scissors. The session may end with a writing activity, including copying letters, and a parent consultation.

“One hour a week really does make a difference,” Ratigan said. “A lot of it is breaking that negativity of believing ‘I’m not a writer.'”

CAPABILITY

Capable Kids provides services individually as well as small group classes. For more information, call 926-0862, or visit www.capablekidsllc.com.