By Ruth G. Stimson

From “Forest Notes” — No. 75 — Fall 1962

New Hampshire’s Conservation Magazine

Official Publication of the

Society For The Protection of New Hampshire Forests

If you had been a colonist in the 1600’s, what would you have looked for before settling along New Hampshire’s coast? Tree lovers would have admired the fine white pines, hemlock, cedar, elm, ash, hickory and beech. Coopers would have visualized the staves from the massive oaks. Fishermen would have tried their luck. Farmers were attracted by the salt marshes, according to Joseph Dow’s History of Hampton. It was this feather of the area, later to become Hampton — the vast salt marshes, covered in summer with grass, level as a prairie, that attracted notice of the government of Massachusetts. They gave permission to a group of farmers to explore the Winnacunnet [Hampton] River. Men and women, under seventy-seven year old Rev. Stephen Bachiler, sailed up the river in a shallop in the fall of 1638. The Indians called the place where they landed “Winnacunnet, a beautiful place of the pines.”

At the commencement of the settlement, house lots were granted to the people by a committee appointed by the General Court for that purpose. The right of disposing of the land was vested in the town. Individuals weren’t allowed to select land for themselves where, when, and in what quantities they pleased, nor did the town by vote grant to each freeman the same number of acres. Some had worked harder than others in making the settlement.

Rev. Bachiler received, besides his house lot, 300 acres and fourteen other people had lesser grants down to 80 acres. The largest acreages went to the farmers. In 1640 the town determined that one-half of the ground was to be upland if possible, and of the other half one-third was to be in fresh meadow and the rest in salt marsh. Later the town gave grants to 55 more, including three widows. Only five or six of the grants were called farms.

The town appointed a Board of Woodwards to assign to individuals what trees they might take from the common land. This was evidence of great foresight and regard for the welfare of succeeding generations.

The people built their log houses around the Meeting House Green just north of the marsh, on lots up to ten acres. Under the school law of 1647, since there were fifty householders, the people had to maintain a free public school for both boys and girls. John Legat, the first teacher, was paid twenty pounds in “corne, cattle and butter at the current price” on a quarterly basis.

In that early period people raised cattle and were indebted to the extensive salt marshes. Pastures were unfenced, although there was a fence and three gates to separate upland and marsh. The people drove their cattle to the Common, and town-appointed herdsmen and shepherds took care of them all day. Wolves were a constant threat, and a bounty was paid in corn.

The Great Ox-Common from just north of Great Boar’s Head, south to the Hampton River, westerly to the junction of the Brown River and back to the starting point, contained upland, marsh and thatchland. In 1641 it was set aside as an ox-common “to the world’s end.” Pasturing horses were forbidden because of the hay and sweepage. The Common was surveyed and belonged to the inhabitants in equal proportion in common with no actual land subdivisions. Later in 1714 shares were distributed to private lot owners by town vote. Any income was to be divided among shareholders according to their share, but in conveying shares, there was no transfer of land, but of so many shares of the whole in the Common.

The entire marsh was well ditched at right angles to some creek or the river. This kept the water from killing out the hay. There were trespassers on the common lands even in 1706, so the townspeople ordered prosecutions. About the same time the selectmen assessed share in the Town’s common land, to raise part of the province tax. It was ordered that sweepage of the common thatchland should be given to the poor of the town. None of the thatch could be mowed until late in August.

In 1655 there was a culler of staves, as great quantities were taken by the town in payment of taxes assessed upon the inhabitants. All had to pass through the hands of the culler. People were licensed by the selectmen to fell trees on the common land to make up to 500 staves for each share of the common owned.

When public convenience necessitated a road across the marsh to Hampton Falls, two ditches were dug and a road made in between. Settlers were designated to maintain the road where it crossed their marsh land or be fined.

Boats were built in Hampton along the river, and schooners were owned by Hampton men for fishing and freighting along the coast. Shipping commenced soon after the settlement began, because Hampton River was of sufficient depth to admit vessels of 70-80 tons even though its entrance was difficult because of sand bars and sunken rocks. Probably most of the boats were for the fishing business, even though the local people were primarily farmers. A 40 ton brigantine, Increase, was built in 1699.

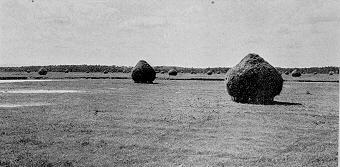

With the boats came the need to save distance. David Nudd, a boat builder, for a hogshead of rum, had a canal dug which was wide enough to float any vessel that could come up the river to the Hampton Landing. The Nudd Canal saved time and two miles of travel for the gundalows. These boats were used to bring hay to the Hampton Landing on the river. One man towed while another stood on the boat with a long oar or pole to push it from the river bank. Other men rowed. A load was made up of five tons or 150 haycocks. The hay was placed on staddles or wooden posts for drainage on the salt marsh. It was necessary to leave the landing on a full tide, load up, and float back on the next full tide. Gundalows were used also for pleasure along the Hampton River to the Clam Flats, and the Willows section. People had chowder parties, went clamming, lobstering, and fishing as well as swimming and shooting Yellowlegs and Ringnecks.

In the winter when the marshes were covered with snow-ice, ox or horse teams were driven to the stacks before the warm spell, when the marshes softened. Of course some horses and cattle got out and made their way across the frozen marsh to the haystacks. The salt marsh hay was a great asset to the first settlers. Year after year it was God’s gift. All they had to do was go out and cut the grass. The farmers mixed the salt hay with coarse meadow hay.

A great storm and uncommon tide twenty inches higher than usual on Feb. 24, 1723 inundated the Hampton dunes and marshes to form Meadow Pond. Eels were caught in traps without bait in the fall when they were coming from the sea to winter.

History records a 40′-50′ whale being cast up in 1756 and shipwrecks off Hampton. The first stagecoach was a memorable event for th early people, when it went through Hampton on April 20, 1761 on its way across the marsh from Portsmouth to Boston. The round trip was six dollars.

The same year the town voted to “rate” or tax pasture and woodland for the first time. The best pines were marked with a “broad arrow”, and claimed as the exclusive property of the English crown for masts for the Royal Navy. The brand was a warning so that no man might dare to cut down such a tree even on his own land because of the heavy penalty. Mast chips brought goods the colonists were forbidden to provide themselves, and carried away the best pines. It was little wonder that most ships were hated objects. When one went ashore in Hampton there was a riot with clubs and staves over the loot.

Seaweed laws had to be passed with a 40 shilling penalty for people removing it or rockweed. Laws were even passed to protect the trees on the Ox-Common. There were fines for cutting beach grass and peas. The settlers realized these plants prevented the sand from being blown away and exposing the inland to inundation. When private citizens found squatters on public lands at Hampton Beach, they resolved that “Hampton Beach was and should be preserved for public good.”

Fishermen used Sargent Island or Island Pa;th for building stages and curing fish. They also had fish houses at North Beach. In the 1800’s shore fishery was carried on by forty men all year. They used wherries in winter and whale boats made of oak and pine in the summer and fall. The boats had sails and oars, and were highly regarded for weathering storms. The men caught hake soon after dark, cod of 30 to 36 pounds about midnight, haddock and an occasional halibut until daybreak. One or two tons was a typical catch.

Fishmongers came from Vermont with horse-teams in the winter to get the catch to seel in Canada. In summer the fish were salted. David Nudd of canal fame had a salt works in 1827 near the landing for his boats. He produced 1200 bushels per yer, but gave up the works by 1840 as salt prices fell. Winter fishermen had another canal that was made between Blackwater River in Seabrook to Salisbury and the Merrimack River. It was an inland waterway for forty years, until it began to fill in. The fishermen went down to Plum Island and Ipswich River to dig clams during low tides. A good digger often secured ten bushels in a tide. The men would fill their boats with from 70 to 100 bushels and return.

Rarely did the fishermen risk frightening the fish by throwing out an anchor. One man used the oars to keep the boat from drifting from the fishing ground, while the other managed the hand lines. He turned from one to another as fast as he could haul and take off the fish and rebait the hook.

Later centerboard wherries used sails, and trawls were substituted for hand lines. These had hooks placed 6′ apart on the whole length. They were carried in tubs with a half mile of line in each. The hooks were baited with clams to attract cod and haddock in winter, and with herring and porgy in summer for all kinds of fish. Each boat carried four trawls, which were set in the afternoon and hauled at daylight the next morning. An average catch was bout 500 lbs. The winter of 1889081 saw a record with 30,000 pounds taken in one day. Later pirate seiners drove off the porgies by catching them for oil. The hake that fed on them then disappeared, and then the haddock. Daily catches went down to 100 lbs. The mackerel fishery was ruined by 150 vessels seining daily all summer. Lobster fishing held its own better than sea fishery, but law had to be passed on seining, or all fishing would have stopped.

While fishing was an industry, so were the mills. The first grist mill was built and run by Richard Knight in 1640 at the Hampton Landing. There were others in town plus sawmills. These became a necessity when the log houses gave way to framed buildings. Every river and large brook had a mill of some type. Altogether there were twenty-eight: grist, saw, and fulling mills. There was even a Tide-mill on the Hampton River for grinding the town’s corn, with the sixteenth part thereof for the miller. The millers had responsibilities not to flood any man’s hayfields in summer. The tide-mill was demolished in 1879 by the town for the supposed benefit of the marshes, on which the water had been kept back, till they had become of little value.

There were two tanneries at Bride Hill and back of the Garland homestead. When the town found that oak trees on the commons were being cut to strip their bark for use in tanning hides, it voted that all such bark would be forfeited, and the offender fined five shillings for each tree so stripped. Through the years great storms were recorded. In the middle and late 1800’s gales ripped through the Hampton marshes. They lifted hay from the staddles and swept the cocks away. Salt spray came into town. Fish and bath houses were badly damaged and part of a railroad was swept away. In February and March of 1962 when the Atlantic Coast was severely damaged by very heavy seas, the Hampton marshes served then, as in the past centuries, as a buffer to the storm tides. Hampton River both drains and waters the salt marshes as the tide ebbs and flows, thus rendering them productive.

Among New Hampshire’s people today there are some who ask what good are these marshes. They would like to dredge and fill them, to create houselots to attract more people to New Hampshire’s coastline. With more new land and residences, they hope to alleviate the tax burden. This line of reasoning regards the Hampton marshes as wasteland.

Marshes are wetlands, not wastelands, in land use classification. In their natural state wetlands have the following economic values according to the U. S. Dept. of Interior Fish & Wildlife Service:

1. Reduction and prevention of erosion.

2. Stabilization of runoff of excess water from inland.

3. Home for waterfowl and shore bird population, with resulting recreational appeal, and source of the nutrients for shellfish harvest.

4. Forage fish habitat. Our tidal waters are among the most fertile of the sea with large fish cruising within striking distance of the tidal food supply.

5. Tidal marshes are very valuable as a buffer for storm tides that damage man’s possessions. Look to the south of New Hampshire for evidence of destruction of property in New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and even to Florida in 1962.

Salt marshes are unrivaled in their natural state for seacoast protection, as the vegetation is resilient and emerges undamaged from storms that will sweep away houses and stones in breakwaters. For these reasons, recreational, scientific, and economic, conservation-minded citizens and organizations are concerned and hope to take measures to preserve the Hampton marshes.

See also Saving The Salt Marshes By Ashlee Palmer & Nancy Devine.