Story & Photography by Stephen T. Whitney

New Hampshire Profiles, June 1971, Vol. XX, No. 6, 75¢

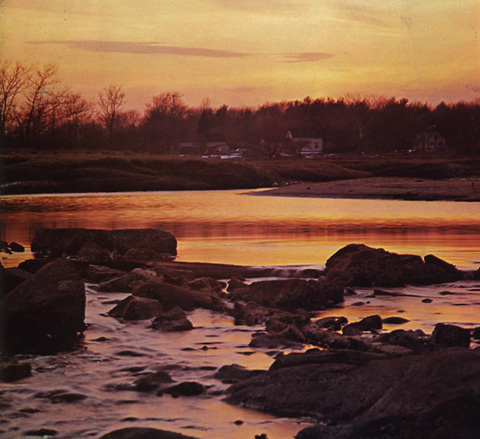

Between the bulwark of beaches and headlands that form New Hampshire's shoreline and the uplands of its coastal plain, one finds an extensive maze of tide lands. Sheltered from the ocean's constant fury, it is coursed by tidal rivers and creeks that meander lazily through a random sweep of salt marsh. These are fragile lands, easily altered by both nature and man.

Nature's wounds heal readily, often in ways that compensate for the damage that has been done.

Not man's. In his haste to turn matters to his own advantage, he leaves wounds that he himself can not make well and which nature can mend only by change.

Man has not always been careless with the tidelands. When he first settled along their edge, he guarded their sanctity prudently for they provided fodder for his cattle. Yet two years after he had first settled in Hampton, he made his first move against the marshes.

Hampton's first families favored two sites for their new homes. One was around the village green that was laid out north of Taylor River. The other was about the Falls, south of the river in what a hundred years hence would be the town of Hampton Falls.

Man's initial intrusion upon the salt marsh was prompted by his desire to forge a passable way between the two settlements. It was an ambitious undertaking for it is along the banks of the Taylor River that the tidelands make their deepest inland penetration. After six years' effort and considerable controversy, a roadway of sorts crossed the marshlands on a rudimentary causeway just west of the present location of US 1.

The burden of its maintenance continued to plague the inhabitants of Hampton for another century and a half. Relief came only when the Legislature authorized the formation of the Hampton Causeway Turnpike Corporation in 1808. Although the corporation succeeded where the town had faltered, its tolls - from which the Hampton citizenry were exempted - were never popular. Less than twenty years after it came to the rescue of the causeway, the corporation sold the improved highway back to the towns and the road across the marshes became a freeway.

It is not reasonable to expect that Hampton's early inhabitants were aware of any change that their causeway worked on the salt marshes of the Taylor River. They were occupied with more immediate problems, not the least of which was the continual struggle to keep the river's tides from washing away their causeway. Nor can it be expected that they recognized that the vitality of the marsh depended on the freedom of the flood and ebb of the tide to follow their own courses across the tidelands.

In the early years of Hampton, it was the great salt marsh near the beach that was held in favor. Set off in 1641 as the Great Ox-Common, it lay between the outer beach and John Brown's River from a point north of Great Boar's Head to the mouth of Hampton River. It included salt marsh and thatch ground, sand dunes and the uplands of Great Boar's Head. Access to the common land was provided by another early undertaking - the beach causeway.

Unlike the Taylor River causeway, the passage to the beach did not threaten the salt marshes. It crossed the lower reaches of a fresh meadow above the run of the tide.

In the early decades of the coastal settlements, the great changes came not from the hand of man, but from nature. Dramatic changes occurred in the coastal wetlands between Great Boar's Head and Little Boars Head. When Hampton was first settled, there was a large fresh meadow under Little Boar's Head drained by the Little River which emptied into the sea at Plaice Cove. South of the outlet, in the direction of Great Boar's Head, Nilus Brook flowed through an extensive bog area known as Huckleberry Flats. Below the Flats, the brook flowed through Great Pond (later known as Beach Pond) just a few yards north of Great Boar's Head before it turned abruptly westward to join John Brown's River.

A late winter storm of unusual severity altered the topography of the area in 1723. Driven by the storm, the ocean broke through what was known commonly as 'sea-wall beach' at a point now marked by the Hampton-North Hampton line, permitting the Little River to empty into the sea at this point. As a result of the breach, the tide now could flow into the meadows behind it, converting the fresh meadows to salt marsh.

Inland flooding by the tides of the same storm tore up a large portion of Huckleberry Flats, creating Meadow Pond. The debris torn from the bog choked the downstream course of Nilus Brook. To release the water impounded in the new pond and relieve the threat of flooding, a ditch was dug on a direct course from the lower end of the pond to John Brown's River.

Having provided Little River with new egress to the sea and created salt marsh where there had been fresh, nature seemed to repent. Scarcely half a century had passed before the Legislature was asked to grant relief to those with an interest in the 120 acres of salt marsh along the Little River. Although the act of 1780 permitted the men to remove the stone and gravel that choked the mouth of the river and damnified the meadows and marsh behind the beach, it did not provide permanent relief. Today the outlet is high and dry, filled with beach sand and grasses. At the far end of the beach, a culvert has been carried under the road, releasing the waters of Little River and admitting seawater at the peak of each tide.

The most prominent single incursion of man occurred on the salt marshes in 1840. Beginning at Brown's River on the Hampton Falls-Seabrook line (not to be confused with John Brown's River across the marshes in Hampton) and cutting across the marshes of Falls River and Taylor River, the Eastern Railroad put down its roadbed. The impact of one causeway stretching across two miles of salt marsh with only four bridges through which the tides could run, threatened much of the coastal marshland.

For some years, the damage was minimized by the efforts of the farmers who wished to preserve the salt meadows for hay. Long ditches were cut so that the tide would not stand slack on the marshes and a balance between man and nature appeared to have been struck.

Change had only been deferred. Farmers stopped taking hay from the marshes and the ditches were neglected. Today where tides no longer sweep the marshes freely, stagnant pools of brackish water now stand, refreshed only by the spring tides. Where the water stands, the grass dies and a salt marsh becomes a mud flat.

Unfortunately, nobody asks about trains anymore. The roadbed will remain long after the last train has crossed the marsh. But the noose that was dropped so loosely on the shoulders of the tidelands has been gradually tightened.

Man continues to encroach upon the marsh. When the New Hampshire Turnpike was built less than two decades ago, the upper salt marshes of the Taylor River were cut off from tidewater by the highway and converted to fresh meadows. More recently, the Hampton Beach Expressway crossed salt marshes that the town of Hampton had moved to save in 1879. The highway crosses by the site of a tidemill that was granted in 1681. The town bought the mill nearly one hundred years ago to preserve the marshes that were being destroyed by the flooding of the mill's tide pond.

Man grows careless gradually. As the farmers' interest in the marshes waned, a new phenomenon was developing along the beach: It was becoming a summertime oasis. At first man hurried to claim the headlands and dunes that rose above the ocean. When they were gone, he turned the other way. Foot by precious foot, he is covering the marshland with a jungle of summer cottages.

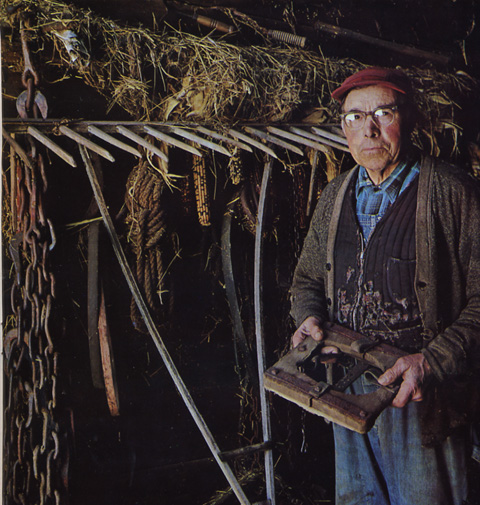

People excuse the incursions by reasoning that one has to grow up at the head of a fresh meadow that reaches out to the tidelands below or be born with a pinch of salt in one's blood to sense the beauty of the marshes. It can also be an acquired affection. In imagination as well as memory, one can view the weathered staddles that stand like stubble on the marshes and through the soft light of yesteryear, see golden haycocks standing above the tide.

The Salt Meadows Photo Gallery