Will Hampton bring down the gavel on town meeting, ending a 350-year tradition of participatory democracy in its purest form?

By Amy Miller

Seacoast Sunday, May 17, 1987

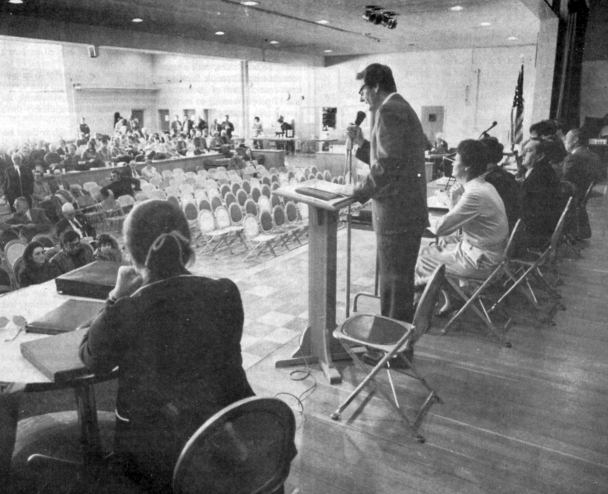

Hampton moderator Al Casassa speaks before rows of empty chairs at a 1980 town meeting.

Sparse attendance at town meetings in recent years is one reason the town is considering

new forms of government.

In the 1960s, the people of Hampton outlawed the sale of alcohol in the “seasonal business district,” and for years Lamie’s was the only place in town where liquor could be sold — and only to non-residents of Hampton. Former selectman Louisa K. Woodman recalls with amusement the town meeting when the vote was taken. “The issue of liquor came up on the floor after dinner and some of the people who were the most vociferous had the strongest odor of alcohol on their breath.”

While Woodman was sitting on a bench beside Route 1 one recent morning talking about past town meetings, cemetery trustee Roland W. Paige walked by. “That too became a big issue at town meeting,” she said, looking towards Paige — “the way the cemetery was being handled.”

In 1985, trustees of the cemetery decided it was too expensive to maintain the lawn around up-right gravestones and no more of these stones would be allowed. The townspeople, not happy with this ruling, voted to designate a particular section of the cemetery for stand-up gravestones.

“This is the kind of thing that, when the town goes to a non-town meeting form of government, if that happens, will be decided by the board of selectmen or council or whatever you want to call it,” Woodman said.

Since 1639, when settlers incorporated this blustery, coastal region, citizens of Hampton have been going to town meetings to make such decisions — some far bigger, some much smaller. For three and a half centuries, the residents of Hampton have been deciding what roads will be paved, which streets will be patrolled and how much they will pay to keep the town well run.

In 1888, voters approved $4.50 to Selectman Enoch P. Young for “three journeys to Exeter for advice.” In 1959 they voted to raise $500 to install a fire alarm box on Leavitt Island. And in 1987, voters agreed to add $115,000 to the budget for four additional patrolmen.

Now, though, as the town prepares to celebrate 350 years of history, there are those who think there could be no better birthday present for Hampton than to rid the town of the annual meeting. In short, they say, this historic form of government just doesn’t work anymore and it’s time for the town to hire some qualified decision makers.

Townspeople voted by a 3-1 margin this spring to establish a commission to review the town’s current system of government — a system many say shows obvious signs of failure.

This year, a few hundred people attended the March 14 town meeting — anywhere from 40 to 300-plus, depending on the time of day. A vote on a bond issue showed 260 people casting ballots, about 3 percent of some 8,000 registered voters. About 32 out of every 33 voters stayed home, watched TV, went shopping, went away for the weekend or did any of a million things other than participate in the way the town would run.

Many of the people attending the day-long meeting in the regional high school stayed only long enough to vote on the bill that drew their interest, leaving a handful of citizen of citizens to make all the decisions for 8,000 other voters — how much taxes they would pay and how much police protection, roadwork, and social services they’d get.

In the past few years, selectmen in Hampton have begun to talk about the deficiencies of town meetings. Apathy, growth, an influx of people not familiar with the town meeting system and a more complex government have been blamed for the demise of this New Hampshire tradition.

As a result, selectmen asked the town this year, with a winter population of 13,000 and a summer population of about 20,000, to vote on an article that would set up a charter commission to consider alternate types of government. The citizens apparently agreed that change should at least be considered. In a 942-369 vote, the people said “yes” to a charter commission and elected six of the members. The other three members were appointed by selectmen.

Members of the committee elected by the citizens are Ashton Norton, Peter Janetos, Mary Louise Woolsey, Melody Dahl Gabriel, Louisa Woodman and Robert Lessard. Selectmen appointed Glyn Eastman as selectmen’s representative and Jon Williams and Raymond Alie as citizen members. Of the group, four have been selectmen in the past and one is a current selectman.

Meetings are held at 7 p.m. on the second and fourth Thursday of the month, the second Thursday in the selectmen’s meeting room and the fourth Thursday at Lane Memorial Library.

By the 1988 town meeting, the commission will have a draft charter proposing what the commission believes would be the best form of government for Hampton. The commission may choose from any of five forms allowed by the state Legislature.

The Town Meeting, often called the purest form of democracy, is clearly far from perfect. A few people decide for the many — people who have not been elected and are not necessarily knowledgeable on the issues at hand.

Perfect or not, though, the New England town meeting is still probably the most direct access to government given to citizens in America, or probably anywhere else. It has a long history with deep ideological roots and is unlikely to die fast, in Hampton or anywhere else.

Only three of the 221 towns in the state have decided to end the town meeting since the legislature passed enabling legislation in 1979. Nonetheless, rapidly growing towns in the southern tier with increasingly complex government are beginning to look twice at the options.

This year, Durham voted to effectively eliminate the annual town meeting and switch to a town council form of government, keeping town meetings as purely informational affairs. Derry and Hudson eliminated town meetings several years ago, and Salem voters have twice turned down charters that would eliminate this citizens’ forum. Bedford is currently writing a charter to this effect that will be considered by voters next year.

While no other towns in the Seacoast are actively considering an end to town meetings, officials in Exeter say the idea has been turned down by voters twice before, and is likely to come up again. Questions about the town meeting form of government come down to questions of power. On one side are those who argue that people who care enough to come to town meetings deserve the power to make the decisions. On the other side is a feeling that a small number of people with special interests, citizens who are not chosen to represent the town, should not be holding the reins.

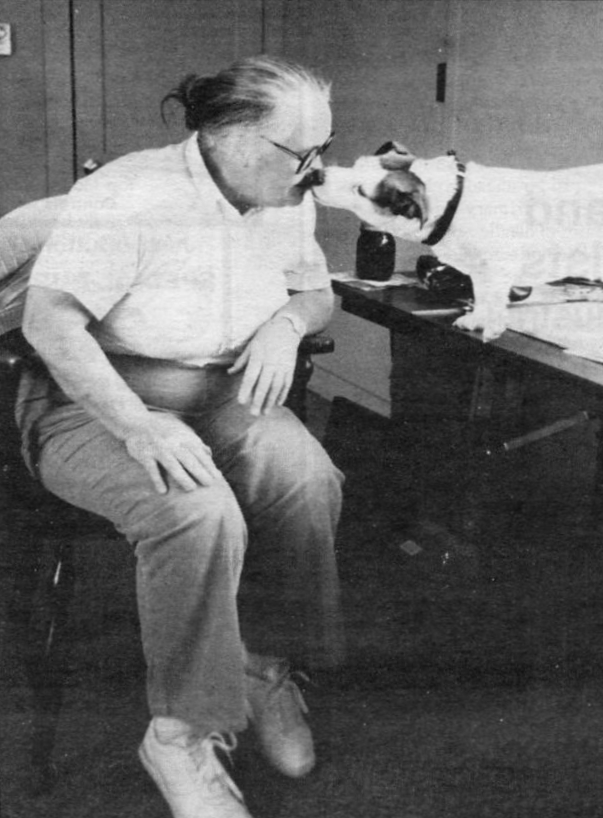

Hampton Town Clerk Jane Kelley, shown with her dog Busby, asks, “Why eliminate town

meetings, after all, they have worked well for three and a half centuries?” [Amy Miller photo]

“It’s worked fine for 350 years. Why fix it?” says Jane Kelly, town clerk, one of the most outspoken proponents of the town meeting. “It’s like they’re taking a wrecking ball to a wonderful piece of tradition and wrecking one of the few things in this town that’s really had consistency since 1638”.

“Once you start shaving off your democratic rights, they get peeled away bit by bit. You’re never going to get them back.”

As citizens in Hampton and town across the Southern New Hampshire begin to consider the failings of the town meeting system, they will be forced to consider their priorities. When they vote to eliminate the town meeting, they may be robbing themselves of the right to make any such vote again.

By getting rid of town meeting, the citizens are giving up the chance to say yes sor no on a myriad of questions that have always been asked of them in the past. Many of the people have been atending town meetings for decades, perhaps all of their lives. Deciding to give up that right is not something many take lightly.

“Does the town of Hampton still want to have people participating in government? Is the citizenry ready to turn over almost all control of local government to a very small group of people?”