Hampton 350

1638 — 1988

Rockingham County Newspaper — July 8, 1988

Hampton Union and Seacoast Online.]

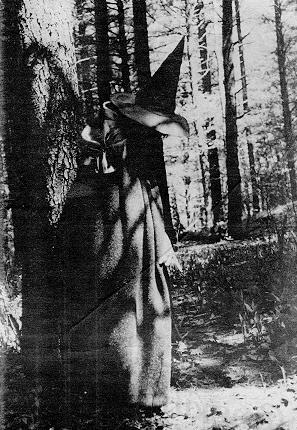

Cole Remembered As Hampton’s Witch

By Bruce E. Ingmire, Contributing Writer

The history of 17th century New Hampshire is incomplete without mention of Eunice Cole of Hampton who, like many English women of the time, was accused of witchcraft.

Widowed in mid life, she became entangled in a series of accusations which eventually led to the loss of her property. Given the 20th century population in the New Hampshire Seacoast, it is hard to imagine that the& 2,000-3,000 residents of that time were also in a feverish competition for Seacoast real estate.

Eunice Cole, better known as “Goody” Cole, was a victim of this fever. Sketchy though the facts are, hunger for land inspired most New England witch accusations. Once Cole’s land — her only source of income — was gone, she was virtually a ward of Hampton and fell into a spiral of begging and resentful charity.

Many New England settlers like William and Eunice Cole first arrived in the Boston area. As servants to Matthew Craddock, the Coles settled at Mount Wollaston, later Braintree. Their minister was John Wheelwright, a brother-in-law of the persecuted Anne Hutchinson and minister of the town. Wheelwright and his followers — including the Coles — came under fire for “antinomianism.” These antinomians, like Anne Hutchinson, preached that God could speak directly to individuals, while Puritans believed God’s only message was the Bible. Puritans dismissed inspiration as delusion or worse, the work of the devil.

Early Accusations

Wheelwright and his followers, who then were in Boston, were banished from the Bay Colony in 1637. Traveling north to Winnacunnet, they established the town of Exeter. The document of incorporation, the Exeter Combination, contains William Cole’s signature. Whether because the Coles were located on land that later became Hampton, or because they moved closer to the coast, they became residents of Hampton.

By the 1640s, when William Cole was in his 50s and his wife was likely in her 30s, the Coles were in court in Salisbury a number of times. The childless Eunice was accused of slanderous speeches. She had insulted her neighbors and had been accused in court.

Starting in 1649, Massachusetts Puritans began to take control of government in all the towns of future New Hampshire. As a result, neighborhood tension in Hampton and Portsmouth took the form of witch accusations. Among the accused was Jane Walford in Portsmouth. Later that same year in Hampton, Goody Cole, long-associated with suspicions of witchcraft, was charged as a witch. Now firmly part of Massachusetts, the newly revised laws of the colony listed witchcraft as a capital crime. Conviction meant death. And death meant the dispersal of one’s land.

Both communities had many members who deeply distrusted the Puritans. in control of their government. There was enough skepticism in the two communities to prevent the women from being transported out of the jurisdiction for trial. Defendants in witchcraft cases, like those of Walford and Cole, were routinely sent to Boston, the capital of the colony of Massachusetts. Conviction assured the confiscation of property. Cole was arraigned in Norfolk County Court in nearby Salisbury and Walford was arraigned in Norfolk County Court in her neighboring town of Dover. In each case, the husband of the accused was alive so no land was confiscated.

In Walford’s case, depositions were taken but no trial was convened. A year later, Walford was exonerated by “a three times declaration.” The justices allowed Jane Walford to continue her independent ways. There was no proof she had intended to or had actually done any harm.

Cole, on the other hand, had lunged at her neighbors and been charged with slanderous speeches. Childless, Eunice may have also suffered silently in Hampton where family and children meant so much. Her actions marked her as mean- spirited.

Hampton and Salisbury, more severe in their beliefs than Portsmouth, had no tolerance for witchcraft. The inhabitants were from eastern and southern counties in England like Essex County, where witch trials had proliferated. (In fact when old Norfolk County was broken up, the inhabitants chose to call the new smaller county, Essex County, Massachusetts.)

No record of Cole’s trial survives; she was obviously convicted of some charge as records show she was incarcerated in Boston. Since there is no early provision for lessening the sentence of death, Cole probably was not convicted of witchcraft. In her first trial, unlike Jane’s case, some harm to domestic animals or malficium was demonstrated in depositions.

Whipped And Jailed

Joseph Dow in his “History of the Town of Hampton, New Hampshire,” says that Cole was whipped, and imprisoned for life. Whipping was often a punishment for outbreaks and uncivil language, and it is likely that, true, to her habit, Cole had been reduced to slanderous threats as she pleaded for her life.

Whatever the reason for the judgment, Cole was incarcerated in Boston. Shortly after her incarceration, Cole’s “ancient” husband lay near death. Eunice petitioned Boston authorities to allow her to go to her husband. In 1662, she returned to his bedside, but he died. He left his estate, except for his wife’s share, to Thomas Webster.

There is no record as to why Cole left the land to Webster, but Cole may have felt that the land was safer in a man’s hands and Eunice could be helped by Webster. Having already fallen under witch accusations, Cole may very well have suspected unscrupulous men would try to accuse Eunice in the pursuit of her land known as the widow’s dower. Little could William Cole have imagined that the prime accusers in Goody’s 1672 trial would be the extended Webster family.

The rest of the land, Eunice’s dower of one-third of the original grant of 1640, fell into the hands of selectmen, who agreed to sell the land to cover the cost of her imprisonment. This short-sighted move would leave the unfortunate woman their ward.

In the stricter standards of the Puritan moral code, she was seen as being foreordained to her shiftless position. Eunice Cole seems not to have developed friends in Hampton. For whatever reasons, she remained a remote harridan. When she came to trial, no one was willing to come forth in her defense.

In fact, unlike many cases here, one segment of the community attacks a woman from another class, Eunice’s accusers included the entire spectrum of rich to poor in Hampton.

Returned In 1671

It is difficult to imagine the lonely desperation this childless outcast must have felt. The blow was the loss of her land.

By 1671, Goody Eunice Cole returned to Hampton and many families agreed to take turns caring for the lonely woman who took up residence near Rand’s Hill The townspeople showed obvious resentment toward her continued pleas for food and wood. In less than a year, in October 1672, charges of witchcraft were leveled against Eunice again.

As life proceeded in 1671, individual families took turns bringing food to Goody Cole. One family that provided food was that of John and Bridget Clifford. There were thirteen members of the Clifford household. Eleven were children with four different surnames. Among the children was the young Ann Smith whose mother had died when the girl was an infant. Her father had abandoned her to the Godfrey family. Eunice may have found in little Ann Smith a lonely soul and reached out to her. Ann certainly had reason to have felt abandonment.

The town wags, however, saw only the evil possibilities. Imagine the cry, “The witch is after my children.” Imagine the frightened children. Of the women who gave testimony, most of them were in the Clifford household. The list included Ann Smith herself, Bridget Huggins and Sarah Godfrey Clifford and Anna Huggins (Bridget’s daughter).

Webster’s ‘Right’

Anna Huggin’s father, who was dead, had been the constable that had earlier whipped Goody Cole. Another witness in the trial was John Godfrey. Godfrey’s mother, Margery, had been Ann Smith’s stepmother at one time. Margery Webster Godfrey was also the mother of Thomas Webster, who had gained the Cole estate at the death of the old man. Alive, Goody Cole was a continuous threat to Webster’s right to the land. It is no coincidence that his family whipped up the furor in 1672.

Jailed in Boston once again, Eunice was tried in Essex County Court but exonerated. We will never know if Webster hatched a plot. The fact is that no matter what the cause, a woman had less political power to fight for her rights in colonial days. When a woman did assert herself, she was seen as overstepping her bounds and ran the risk of accusations. It is a mark of the tolerant justices that her life was spared.

In the fall of 1680, during the tension surrounding King Charles II’s separation of New Hampshire and Massachusetts, Goody Cole was again hauled off to prison. The next summer in Portsmouth, Jane Walford had died but her daughter, Hannah Walford Jones, was accused of witchcraft in Portsmouth. Neither woman was convicted.

Exonerated In 1938

Today, ‘Goody Cole is remembered as the witch of Hampton. Succeeding generations have come to believe she was a witch. In 1938, the town restored Goody Cole to full citizenship, but could not restore her right to the land that was taken from her.

In some cases, the story of Goody Cole has been used to discredit the early Puritans by demonstrating early intolerance. In fact, despite a belief in witches, those early settlers did not panic and let things get out of hand as Massachusetts Puritans did in Salem a few years later.

The irony of the Goody Cole story is that the women who tried to defend themselves appear in the early records. In most cases, the good-wives remain unknown. Few remember, know or can name the wife of Stephen Bachiler, but even the young children of Hampton still remember Goody Cole, the witch of Hampton.

[Bruce Ingmire of Portsmouth has researched Seacoast history since 1970. His annual walking tour of Portsmouth has become one of the highlights of the city’s Market Square Days. The subject of his walk this year was Seacoast witchcraft. His book, “Visual History of the Seacoast,” will be published by Downing Company of Virginia.]