History Matters

By Cheryl Lassiter

Hampton Union , June 30, 2015

[The following article is courtesy of the Hampton Union and Seacoast Online.]

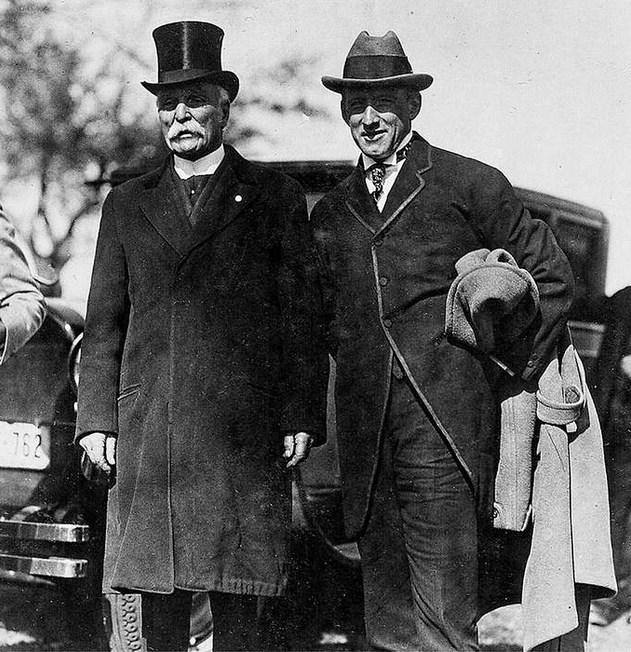

Ira Jones (left) and New Hampshire Secretary of State Hobart Pillsbury at the dedication of Memorial (Founders’) Park,

October 14, 1925. [Hampton Historical Society photo]

It was the 1920s, the war to end all wars had been fought and won, prosperity was rising, morals were relaxing, and a rush of innovations was creating a new mass consumer culture in America. Amid all the “roaring” going on in the country, significant changes were taking place in Hampton, too. The population was increasing as never before, farming and fishing were steadily abandoned in favor of business and manufacturing, and the town, embracing its reputation as a summer tourist destination, boldly touted Hampton Beach as the “Atlantic City of New England.”

A good time to gather up the past

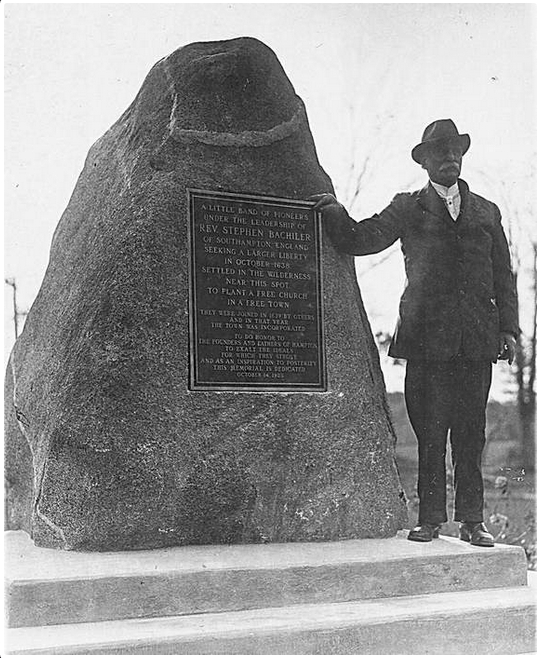

Some felt that now was the time to gather up the past before it slipped away forever. To that end, a group of civic-minded citizens formed the Meeting House Green Memorial and Historical Association, with a mission to preserve the town’s history. They built Memorial Park on the Meeting House Green and dedicated it on the occasion of the town’s 287th birthday, October 14, 1925. Attended by representatives of Hampton’s nine “daughter” towns, the event was capped by the unveiling of a 12-ton granite monument honoring Hampton’s Puritan founders.

The Tuck Museum in 1931

Across the road from the park, in an 1890 farmhouse purchased for the purpose, association members created Tuck Memorial Hall as a place to collect and preserve the town’s historical relics. Nearby they erected a log cabin, their version of the town’s first meeting house. They later acquired the funds to construct the Tuck Athletic Fields to benefit Hampton’s present and future crop of youngsters. Not exactly a conventional historical society function, but they did it anyway.

Ira Jones of Hampton and Edward Tuck of Paris, France were largely responsible for creating the memorial park, hall, and playing fields. The original idea belonged to Ira, who applied the sweat equity in liberal doses and drummed up enthusiasm for the project while Edward supplied the funds and goodwill. Neither were spring chickens, but both would have scoffed at any suggestion that they were far too old to be running around starting new adventures at their time of life. Ira, a retired Baptist minister and funeral director, was 89 years old. Edward, a retired ex-pat banker, was 83.

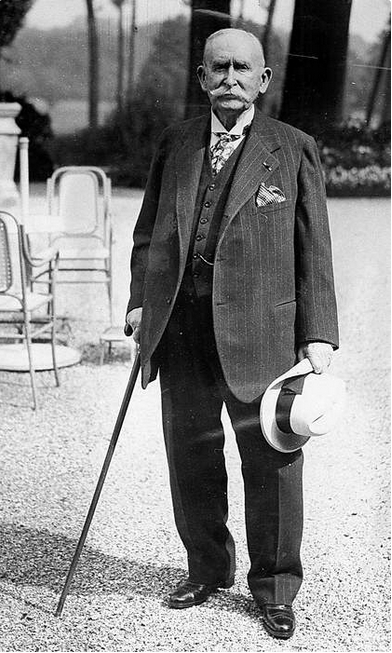

Edward Tuck, the millionaire philanthropist

Edward “Ned” Tuck was born in Exeter in 1842. His mother was Sarah Nudd of Hampton, whose ancestors had settled here in the early 1640s. She married Mainer Amos Tuck, himself of Hampton first-settler stock, his fourth great-grandparents being the town’s first tavern keepers Robert and Joanna Tuck. A graduate of Hampton Academy and Dartmouth College, he became a lawyer, abolitionist, and congressman. His son Edward was educated at Phillips Exeter Academy and Dartmouth College.

Edward “Ned” Tuck was born in Exeter in 1842. His mother was Sarah Nudd of Hampton, whose ancestors had settled here in the early 1640s. She married Mainer Amos Tuck, himself of Hampton first-settler stock, his fourth great-grandparents being the town’s first tavern keepers Robert and Joanna Tuck. A graduate of Hampton Academy and Dartmouth College, he became a lawyer, abolitionist, and congressman. His son Edward was educated at Phillips Exeter Academy and Dartmouth College.

In view of his father’s ardent abolitionist stance, it remains a curious fact that Edward missed out on the Civil War. After graduating in 1862, he was appointed to a diplomatic post in Paris, France by his father’s friend, President Abraham Lincoln. Edward remained in Paris, joined an international banking firm, and married heiress Julia Stell. By the 1880s Mr. and Mrs. Edward Tuck had wealth enough to claim membership in the new Gilded Age millionaire class.

In some measure, they were adherents of Andrew Carnegie’s “gospel of wealth,” and when Edward retired from banking he and Julia devoted their lives to giving away their fortune to worthy causes, with much of their philanthropy aimed at New Hampshire. Long before Edward became the benefactor of the Hampton museum that bears his name, he had given generously to his alma maters and had financed such projects as the New Hampshire Historical Society building in Concord, the Reverend John Tucke obelisk on Star Island, Stratham Hill Park, and the Exeter Cottage Hospital. He was also in the habit of donating $300 a year to his father’s old prep school, Hampton Academy.

Ira Jones, the minister with an idea

From the founding of the town in 1638 until 1810, the Meeting House Green had been the site of a succession of meeting houses. From then until 1883 it was home to Hampton Academy. When plans were being made to move the school building to a new location, there were calls to “put in its place something as a memento of the past.” For centuries this part of the common had been the beating heart of the town, and for some it was a wrenching experience to see it abandoned. But the calls went unheard, and for forty years the Green was a “desolate” place, “growing only weeds and brambles.”

Ira Jones at the Founders’ Monument in Memorial Park, October 1925. [Hampton Historical Society photo]

“Then,” in the words of Caroline Lamprey Shea, the association’s first secretary, “came a man with an idea.”

Ira Jones was born into a Quaker family in Maine in 1836. Rejecting that creed, he studied at New Hampton for the Free Baptist ministry. When war came, he served with the 15th Maine Infantry Co. D until June 1862, when he was discharged as disabled at Camp Parapet, Louisiana. Over the years, he preached in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and every New England state. In 1901 he came to Hampton, bought a furniture and casket store, and hung out his sign as a funeral director. His wife Aurelia Lawrence Jones bought some nice flower gardens attached to an unspectacular Victorian on Winnacunnet Road, not far from the bramble-choked town green. The name of their new home was Roselawn, which Ira emblazoned in raised golden letters on his personal stationery.

Aurelia died in 1913 at age 83, and the following year Ira, now 77 years old, married a 38-year-old nurse named Vina Morgan, who was likely the old lady’s caretaker in her last illness.

Caroline Shea tells us in her elegant little sketch that Ira “came to town a stranger, learned to love its beauties and know its history,” and he “determined to do something to preserve the Green and honor the founders of Hampton.” Aware that wealthy philanthropist Edward Tuck was a regular contributor to Hampton Academy, Ira solicited and received his financial backing. Ned’s first gift of $7,000 in 1925 paled in comparison to the nearly $850,000 he gave to Dartmouth College that year, but it enabled the association to buy the farmhouse and build Memorial Park.

The Jones-Tuck mutual admiration society

Ira and Edward corresponded across the Atlantic as the projects progressed, even swapping photographs of themselves like a couple of giddy school boys.

“I cannot refrain from expressing my admiration of your picture, showing your fine and impressive appearance at your advanced age,” Edward, the young pup, gushed upon receiving the senior Ira’s likeness. “I make a very good showing myself, but I take my hat off to you.”

“I am quite convinced,” Ira replied benevolently, “that you need not take your hat off to anyone as showing a better physical or mental condition for the age you represent. I do most sincerely compliment you.” With his letter he included yet another photo of himself, which he pointed out that “in posture I have followed Paris Style.”

No one talks like that anymore, which makes their exchange all the more charming.

Ira had another admirer in James Tucker, the editor of the Hampton Beach News-Guide. Commenting on Ira’s recent appearance as King James II in a local play, he heaped praise on “that splendid gentleman and rare citizen,” who, “unbowed by his more than four score years, straight as the proverbial arrow and with real majesty in his bearing, moved across the pageant stage, a living symbol of everything that was and is good and worthwhile in the life of historic Hampton.”

Seven months later, in April 1927, just as his plans to build the Tuck Athletic Fields were being finalized, Ira died in his sleep. When Edward heard the news he lamented that it was “a pity that Mr. Jones could not have lived to see [his work] fully completed.” He donated another $10,000, others took up Ira’s work, and the playing fields were completed and dedicated in 1930. Edward would live to see 96 years and no more, all the while continuing his financial support of the Meeting House Green Memorial and Historical Association.

The museum turns 90

If the millionaire or the minister had any serious doubts about the future of their Hampton endeavors, they never expressed it. The association was a legal corporation, and other members stepped in where they left off. Over the years the farmhouse that we know as the Tuck Museum has been joined by a fire-fighting museum, an eighteenth-century barn, and a twentieth-century tourist cabin. The old log cabin meeting house finally disintegrated, its place taken by a nineteenth-century one-room schoolhouse.

The museum and the association, now known as the Hampton Historical Society, together turn ninety years old this year. To mark the milestone, the society has opened a new exhibit, “Gathering on the Green: A History of the Hampton Historical Society and Tuck Museum, 1925 to the Present, with highlights of town, beach, and national events.” On Saturday, July 18 they’re hosting a birthday bash on the museum grounds, with appearances by Vikings at Thorvald’s Rock, the witch Goody Cole, and other things of equally special magnificence. I hope to see you there.

History Matters is a monthly column devoted to the history of Hampton and Hampton Beach. Cheryl Lassiter is the author of “The Mark of Goody Cole: a tragic and true tale of witchcraft persecution from the history of early America” (2014). Her website is www.lassitergang.com .