Battle Honors — World War I

Champagne; Oise-Aisne;

Champagne-Maine; Lorraine;

Aisne-Marne; Meuse-Argonne

From time to time the unguarded affairs of the troubled 20th century world have been allowed to boil over. At such times it became the inalienable duty of the citizens to forego their rights and take arms in defense of their country.

Regardless of how wars have been brought on, there was only one thing to do — fight and win them. That is what the men of the 109th Infantry helped to do during their four wars.

The first call to arms came in 1896 when the Regiment, then known as the 13th Infantry, served its first tour of duty in the Spanish-American War. The second call for the 13th came in 1916 when the unit was sent to El Paso, Texas, to quell border raids during a political uprising known as the Mexican Border Campaign. It was after this campaign that the 13th became part of the 28th Infantry Division and in turn, the 109th Infantry.

The Two World Wars

On May 2, 1917, the Regiment sailed from New York harbor to land at Calais, France, seventeen days later. Here they faced a war which, up to that time, was the greatest conflict in the history of civilization; and here were recorded some of the greatest achievements of the Regiment. After a brief training period with French and English forces the 109th troops were flung into the battle of the First Maine. They fought from the Maine to the final push at Bois de Dampvitoux, making an indelible record for themselves while winning battle honors. at Champagne, Champagne-Maine, Aisne-Marne, Oise-Aisne, Lorraine and Meuse Argonne. Price for their glory was costly as over one hundred per cent of the Regiment was wounded from the time it began at full strength to the day of the Armistice on November 11, 1918. This grim evidence left no doubt in the ranks of the 109th Infantry that they had participated in one of mankinds most terrible wars. There was, however, a greater conflict to come.

We can well be proud, as members of the 28th Infantry Division, to be part of an organization whose record stands so high in the military history of our country.

[“Proudly Served”, right:] The famous photograph of American troops before the Arc de Triomphe, marching in battle parade down the Champs Elysees, shows the men of 1st Battalion, 110th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division in late August 1944. With no time to rest, the Division moved on to fight some of the most bloody battles of the War the day following the parade. (The song that was playing was “Khaki Bill”.)

Battle Honors — World War II

Normandy; Rhineland;

Northern France; Central Europe;

Ardennes; Alsace

The regiment was again federalized in 1941, at which time it became a Regimental Combat Team. Again it was sent to France to be tested on the bloody battlefields of World War II. The men of the 109th battled across France and through the Hurtgen Forest of Germany; elements of the Regiment led the Division into the Rhineland to become the first troops to invade German soil since Napoleon. The 109th Infantry paid with human life and blood as they won battle honors at Normandy, Northern France, Ardennes-Alsace, the Rhineland and Central Europe and they were honored with the Luxemburg Croix de Guerre and the French Croix de Guerre for action at Colmar. The most noteworthy of the 109th Infantry’s achievements during World War II came while the Regiment was resting in the Ardennes sector — considered a quiet sector early in December, 1944. It was then that von Rundstedt launched his vicious, well planned Battle of the Bulge. The unsuspecting 109th Infantry was hit by an entire Yolks Grenadier Guard Division as well as elements of a panzer division, parachute division and other crack German units. Although suffering great losses, (so great were the losses that the Division became known as the “Bloody Bucket Division” by the Germans who saw so many of our wounded troops wearing the red Keystone patch) in three days of bitter fighting, the 109th Infantry completely destroyed the 352d Yolks Grenadiers, at the same time holding its own tactical unity. The 109th had blocked von Rundstedt in the North and doomed the German offensive in the Ardennes. When the tide of battle turned on Christmas Eve, the battle-weary 109th soldiers attacked, threw the enemy across the Sure River, and retook several towns on the original front. Then started the drive into Germany and the final Allied push of World War II.

The Interims

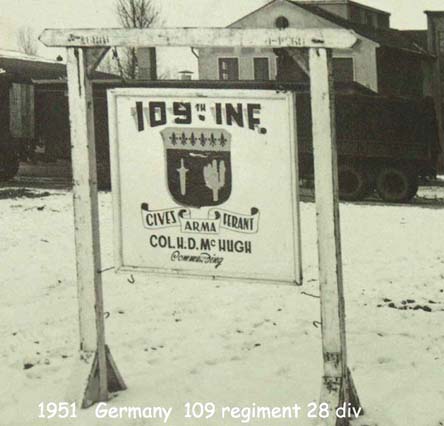

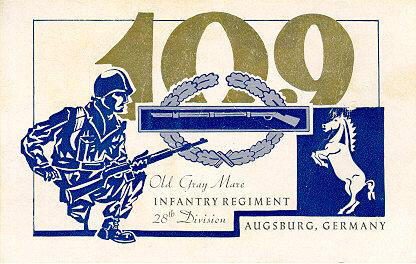

Using arms was not the only job of the citizens of the 109th Infantry. Between the wars theirs was the job of maintaining and training a regiment for future service. To the 109th National Guard Headquarters at Scranton, Pennsylvania, came men of the Regiment from Milton, Carbondale, East Strondsburg, Honesdale, Berwick and Williamsport, Pennsylvania. This function as a National Guard Unit was practiced throughout the interims from the Spanish American War to the present time of the Regiment’s fifth call to duty; this time as an element of the NATO forces in Western Europe. And so from the people of Pennsylvania who kept the military readiness entrusted them comes the Regiment’s motto CIVES ARMA FERANT: “Let the Citizens Bear Arms.”

[CIVES ARMA FERANT: “Let the Citizens Bear Arms.]”

Edward Donald Slovik

February 18, 1920 – January 31, 1945

Company G, 109th Inf. Regt., U.S. 28th Inf. Div.

Edward Donald Slovik (February 18, 1920 — January 31, 1945) was a private in the United States Army during World War II and the only American soldier to be executed for cowardice since the American Civil War. Although over 21,000 soldiers were given varying sentences for desertion during World War II, including 49 death sentences, Slovik’s was the only death sentence carried out!

Early life and draft

Slovik was born to a Polish-American family in Detroit, Michigan. As a minor, he was arrested frequently. The first time, when he was 12 years old, occurred when he and some friends broke into a foundry to steal some brass. Between 1932 and 1937, he was caught for several incidents of petty theft, breaking and entering, and disturbing the peace. In October 1937, he was sent to jail, but was paroled in September 1938. After stealing and crashing a car with two friends while drunk, he was sent back to jail in January 1939.

In April 1942, Slovik was paroled once more, and he obtained a job at MonteIla Plumbing and Heating in Dearborn, Michigan. There he met the woman who would become his wife, Antoinette Wisniewski while she was working as a bookkeeper for James MonteIla. They married on November 7, 1942, and lived with her parents. Slovik’s criminal record made him classified as unfit for duty in the U.S. military (4-F), but shortly after the couple’s first wedding anniversary, Slovik was reclassified as fit for duty (1-A) and subsequently drafted by the Army.

Slovik arrived at Camp Wolters in Texas for basic military training on January 24, 1944. In August, he was dispatched to join the fighting in France. Arriving on August 20, he was one of 12 reinforcements assigned to Company G of the 109th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 28th Infantry Division.

Desertion

While enroute to his assigned unit, Slovik and a friend, Private John Tankey, took cover during an artillery attack and became separated from their detachment. The next morning, they found a Canadian military police unit and remained with them for the next six weeks. Tankey wrote to their regiment to explain their absence before he and Slovik reported for duty on October 7, 1944. No charges against them were filed.

The following day, on October 8, Slovik informed his company commander, Captain Ralph Grotte, that he was “too scared” to serve in a rifle company and asked to be reassigned to a rear area unit. He told Grotte that he would run away if he were assigned to a rifle unit, and asked his captain if that would constitute desertion. Grotte confirmed that it would. He refused Slovik’s request for reassignment and sent him to a rifle platoon.

The next day, October 9, Slovik approached an MP and gave him a note in which he stated his intention to “run away” if he were sent into combat. He was brought before Lieutenant Colonel Ross Henbest, who offered him the opportunity to tear up the note and face no further charges. Slovik refused and wrote another note, stating he understood what he was doing and the consequences of his act.

Slovik was taken into custody and confined to the division stockade. The divisional judge advocate, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Summer, again offered Slovik an opportunity to rejoin his unit and have the charges against him suspended. He also offered Slovik a transfer to another infantry regiment. Slovik declined these offers, saying, “I’ve made up my mind. I’ll take my court martial.”

Court martial

The 28th Division was scheduled to begin an attack in the Hurtgen Forest. The coming attack was common knowledge in the unit, and casualty rates were expected to be very high, as the prolonged combat in the area had been unusually grueling. The Germans were determined to hold, and terrain and weather reduced the usual American advantages in armor and air support to almost nothing. Soldiers indicated they preferred to be imprisoned rather than remain in combat, and the rates for desertion and other crimes had begun to rise.

Slovik was charged with desertion to avoid hazardous duty and court martialed on November 11, 1944. The prosecutor, Captain John Green, presented witnesses to whom Slovik had stated his intention to “run away.” The defense counsel, Captain Edward Woods, announced that Slovik had elected not to testify. The nine officers of the court found Slovik guilty and sentenced him to death. The sentence was reviewed and approved by the division commander, Major General Norman Cota.

On December 9, Slovik wrote a letter to the Supreme Allied commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, pleading for clemency. However, desertion had become a problem, and Eisenhower confirmed the execution order on December 23. The execution by firing squad was carried out at 10:04 a.m. on January 31, 1945, near the village of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines. Slovik was 24 years old.

Slovik was buried in Plot E of Oise-Aisne American Cemetery and Memorial in Fere-en-Tardenois, alongside 96 other American soldiers executed for crimes such as murder and rape. Their black headstones bear numbers instead of names, so it is impossible to identify them individually without knowing the key. In 1987, 42 years after his execution, Slovik’s remains were returned to Michigan and reburied in Woodmere Cemetery, Detroit, next to those of his wife Antoinette Slovik, who had died in 1979. Although Slovik’s wife and others have petitioned seven U.S. presidents for his pardon, Slovik has not been pardoned.

Legacy

In 1960, Frank Sinatra announced his plan to produce a movie entitled The Execution of Private Slovik, to be written by blacklisted Hollywood 10 screenwriter Albert Maltz. This announcement provoked great outrage, and Sinatra was accused of being a Communist sympathizer. As Sinatra was campaigning for John F. Kennedy for President, the Kennedy camp was naturally concerned, and ultimately persuaded Sinatra to cancel the project.

However, Slovik’s execution had been the basis for a 1954 book by William Bradford Huie. In 1974, the book was adapted for a TV movie starring Martin Sheen and also called The Execution of Private Slovik. In addition, Eisenhower’s execution orders and Slovik’s death by firing squad are included in a scene in the 1963 film The Victors.

Kurt Vonnegut mentions Slovik’s execution in his novel Slaughterhouse Five. Vonnegut also wrote a companion libretto to Igor Stravinsky’s Histoire du soldat, or A Soldier’s Tale, which tells Slovik’s story. Slovik also appears in Nick Arvin’s 2005 novel Articles of War, in which the fictional protagonist, Private George (Heck) Tilson, is one of the members of Slovik’s firing squad.