By Paul Estaver

New Hampshire Profiles magazine, November 1964

If anyone tells you he has the solution to the Hampton Beach riots, beware, just as you would be wary of the man who claims to have the secrets of life or success or happiness. There is no single cause for the riots. There will probably be no single solution.

We arrived at this conclusion after a good many evenings at the Beach – not only July 4th and September 5th and 6th but intermittent evenings, busy ones and quiet ones. We read scores of news stories and analyses, corresponded with other resorts who have had similar problems, talked and listened endlessly to police, newsmen, businessmen, town officials, the youngsters themselves, clergymen, social scientists and anyone else who had an opinion.

In the past decade, increased accommodations at Beach and postwar “baby boom” have swelled summer youth population.

For a while as you go through this process you think you are getting a pretty clear picture, but as you learn you discover that what you know with any certainty is less. And as you try to sum it up you find yourself groping badly.

Finally you realize that you have gone through the whole process of education: at twenty you knew everything; at twice twenty nothing could be known. But then comes the period of calm when you realize that a few facts can be reported with some certainty, that some analyses are more thoughtful than others, that if the truth cannot be pinpointed, it can at least circumscsribed.

You read that there were 1,500-2,000, 5,000, 7,000, 10,000, and 15,000 people involved in the riot. Somewhere within that range is a probable answer. The first figure is that of the Portsmouth Herald. The three middle figures were variously used by the wire services and the metropolitan newspapers. Among others, The New York Times quoted 10,000 as a police estimate. The 15,000 figure was casually dropped in a Sept. 8 editorial by William Loeb, publisher of the Manchester Union Leader, who either did not read or did not believe the 5,000 figure quoted by his own newspaper the previous day.

What did the police actually say? Lt. Paul C. Leavitt of the Hampton Police, Col. Joseph Regan, superintendent of the N.H. State Police, and Capt. John J. Marchand, in charge of the Exeter division of the State Police, all agree that it is not possible to estimate a moving crowd with any accuracy. Lt. Leavitt and Col. Regan would make no closer guess than 2,000 to 5,000. Capt. Marchand ventured 2,500-2,800, with a maximum of 3,500. Many others who were at the scene verify these rough estimates.

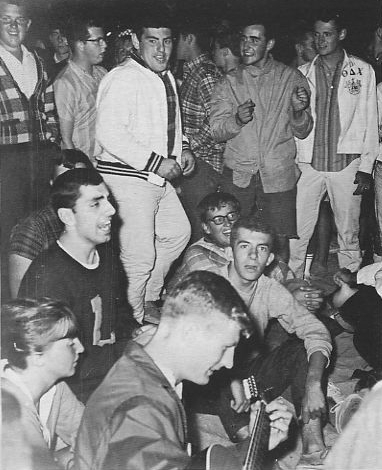

Youngsters ranging in age from very early teens to early twenties strum guitars, sing, or just hang around waiting.

But of course Time magazine used the 10,000 figure. They qualified it by saying “as many as,” but the result is that a number probably two to four times the actual count is firmly fixed in the minds of the public. If we have no clear idea even of the crowd’s size, we will have difficulty in establishing effective preventive measures in future years.

The reporting of the property damage has been many times more inaccurate. A figure used by Linnea Staples in the Sept. 13 N.H. Sunday News was “at least $300,000.” On September 16, Ralph McGill quoted $500,000 in the Boston Globe. The fact that his was an otherwise thoughtful article makes his error all the more lamentable, for his figure was between 25 and 60 times the actual amount.

At this writing, insurance company estimates show the damages will total something more than $8,000 and less than $20,000.

If it is this difficult to establish the physical facts of the Labor Day weekend at Hampton, how much more difficult is it to analyze the motives of the crowd itself. How easy it is to cry out, “Moral decay,” “The Beatniks,” “The scum of youth,” or to throw the blame on the parents – and to look no further.

Perhaps even more unfortunate have been the political repercussions of the riots, as charges and counter-charges appear in an election year over the question of who called for the National Guard, and when. A close scrutiny of this situation suggests three conclusions: First, more of the responsible authorities felt, with apparent justification, that adequate measures had been taken for Labor Day eve; Second, the subsequent charges of negligence have been a matter of closing the barn door after the horse was gone; Third, no clarification of the problem can come from placing the blame wholly upon any single individual. Finding a scapegoat solves nothing.

Most regrettable of all, we feel, are the charges that the riot this year was communist-inspired – regrettable, again because this is seeking the easy answer. The fact is that no one yet has brought forth evidence to substantiate the charge.

The first person we heard to suggest that communism was behind the scenes was a policeman at the scene. He based his belief on the fact that the rioters looked “older than just kids” and that they looked intelligent. Subsequent allegations of communism have had little more basis.

Perhaps the most misleading of the communist cries were those of the N.H. Sunday News of Sept. 13. The front-page banner headline for that day reads: “‘Red’ Leaders Plotted Hampton Riot,” which is about as specific as you can get. The statement is modified slightly in the three-column headline over the story itself: “Hampton ‘Pinks’ Took Page from Red Manual.” The actual story, by Maurice McQuillan, further qualifies the headline by stating: “Consciously or not, they followed Red rioting and terrorist techniques to the letter,” which is quite a come-down from the banner-head quoted above. Examination of McQuillan’s article reveals that the Hampton rioters did not at all follow Red rioting and terrorist techniques to the letter, but that the communist blue-print and the occurrences at Hampton are only superficially similar; they have in common only what all civil disorders have in common – masses of people, confusion, and disruption of transportation.

The only other substance to the article is the “hunch” of various state, county, and local officials that communism was in the background. An editorial in the same issue of the Sunday News restates McQuillan’s thesis as though it were based on solid fact.

Much has been said about the organization of the Hampton riot this year. The aforementioned Sunday News article takes much of its assumption from the fact that the riot was planned. But how planned, by whom, and for what purpose?

At this point we enter upon an evaluation of the riot crowd with fragmentary evidence which must be examined and interpreted with great care. To a considerable extent we are dependent upon the observations of those at the scene, and we must be careful to weigh one observation against another to come as close as possible to the truth.

It seems indisputable that the first and relatively spontaneous disturbance of four years ago, when a horde of youngsters staged an impromptu snake-dance and blocked traffic on Ocean Boulevard, has now grown to a Labor Day ritual whose reputation is sufficiently widespread to draw crowds of both undesirables and spectators specifically for the event.

A year ago the youngsters were talking in terms of the “3rd annual riot,” and by 1964 the tradition was firmly established. News reports have mentioned “Hampton Beach or Bust” signs as far away as New Jersey, and there have been widespread stories of printed leaflets which said “Come to the 4th Annual Hampton Beach Riot and See the Casino Burn,” or words to that effect. Newspapers indicated variously that these were distributed through Massachusetts, New England, and down the Eastern Seaboard, and one story quoted the Maine State Police as having one such leaflet in their possession.

However, Trooper Robert Nichols, of the Kittery, Maine, barracks, says the story is untrue. Nor have either the New Hampshire State Police or the Hampton Police ever seen the leaflet. We have tried in vain to find one – or even to find a witness who will swear he saw one – and have about concluded at this point that the story is simply a well circulated rumor.

If such a flier were actually distributed, it seems likely that at least a few would have found their way into the hands of the authorities. If no such distribution was made, it may be rather important to establish the fact, since the concept of distribution indicated some sort of distributing agency or organization.

It seems more likely that previous years’ news stories and the grapevine were sufficient to draw the Labor Day crowd, and that its makeup was not recruited but spontaneous.

In effort to analyze the crowd, we obtained from the Hampton Police Department a list of those arrested from Friday through Monday. The list did not contain names but was arranged by age, type of charge, and home town. Of the 155 listed, 121 were from Massachusetts, 17 from New Hampshire, six from Rhode Island, four from Connecticut, two from Vermont, one from New York City, and four were servicemen whose home addresses were not given.

The greatest number of arrests – 93 – was on the charge of participating in a riot. On the lesser charges, there were 16 for disorderly conduct, 3 for disobeying an officer, and one for possession of fireworks. In addition, 28 minors were taken in for illegal possession of alcoholic beverages, and 14 persons were arrested on a drunkenness charge. Police note that most of the arrests in these two categories were prior to the Sunday night riot and that drinking played little part in the riot itself.

Ages of those arrested were as follows: 15 (four); 16 (five); 17 (26); 18 (39); 19 (38); 20 (27); 21 (nine); 22 (two); 23 (two); 26 (one); 27 (one); 33 (one).

Here we do have some fairly substantial evidence – enough to give at least an indication of the make-up of the crowd at large. It is of course, a list of arrests, not convictions, specifically it is a list of those whose behavior was conspicuous enough to warrant arrest. When all the cases have been tried, it would be most worthwhile to examine the list more closely and the court evidence as well for an even more exact crowd analysis.

For the present, we can observe that the great bulk came from Massachusetts, not from distant points. The Massachusetts figures can be further broken down as follows: Greater Boston and North Shore – 62; Springfield Area – 22; Merrimack Valley – 17, Central Massachusetts – eight. From Holyoke alone, 13 were arrested, and there were 11 from Somerville, eight from Worcester, and five each from Stoneham, Arlington, Lawrence, and Lowell.

Further city-by-city analysis suggests that the Labor Day crowd was infiltrated with many small groups of undesirables numbering from two or three to a dozen or more.

A consensus of reporters, police, and other observers indicates that the total number of disorderly young people at Hampton Beach in 1964 was approximately the same as in 1963, despite the fact that police set up vehicular road blocks at all entrances to the beach shortly after 3:00 p.m. on Sunday afternoon. How big the 1964 crowd would have been without the road blocks is a matter of speculation, but obviously it would have been considerably larger.

There are other significant differences between 1963 and 1964. A year ago the Hampton Police and their auxiliary forces hired for the Labor Day weekend had to cope with the crowds unassisted until approximately 11:00 p.m. when a body of State Police came to their assistance. This year there were 85 State Police at the beach from 2:00 p.m. Sunday and slightly smaller numbers Saturday and on July 4th.

Last year the Hampton Police had not undergone the riot drill which they have had this year. In 1964 the Hampton Police auxiliaries were all professional from various other New Hampshire cities, not the semi-professional, part-time policemen of previous years.

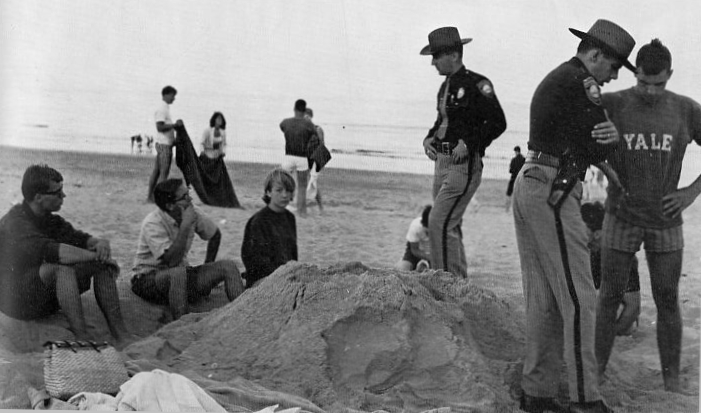

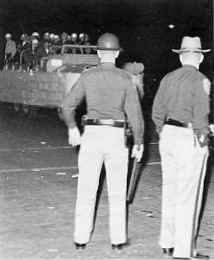

Before it started — troopers chat casually with young people on sand.

Even more important, the Hampton Police had, through the summer, adopted the “tolerant but firm” policy advised by Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, authorities. Minor infractions of petty regulations and harmless horseplay were over looked. More serious offences were dealt with quietly, but quickly and firmly. The State Police followed this same policy until the riot had actually begun Sunday evening.

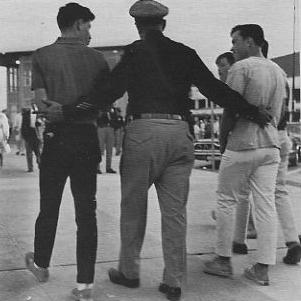

Trooper’s friendly gesture in effort to keep peace without force.

On July 4th the “tolerant but firm” method paid off. The situation was very similar to that of Labor Day 1963, Gangs of young people congregated on the Boardwalk (actually, it’s cement now) and on the beach, singing and chanting – some in good humor, some with vulgar hostility. Firecrackers were hurled indiscriminately. Trash baskets were set afire. A lifeguards’ stand was rolled up fromthe sand and eventually partly destroyed. The tension was tremendous.

But no riot ensued. Police moved in quietly, grabbed the worst offenders and proceeded firmly but politely to break up the crowd and keep it moving until it dwindled away some hours later.

“What a difference!” said one businessman who had previously been critical of police methods. “This year – no dogs, no whistles, no running, no shouting. This is wonderful!”

September 5th, Saturday night, was essentially a repeat performance of July 4th, except that now all tempting combustibles had been removed, including wooden seats, trash baskets, and lifeguard equipment.

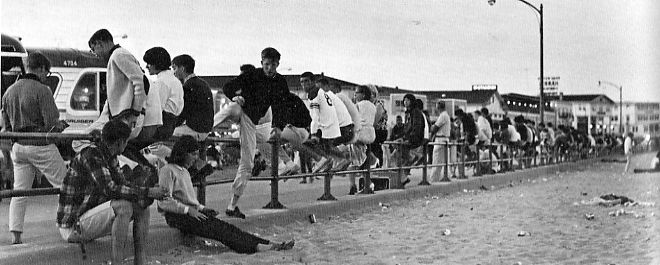

Saturday night, Sept. 5, songs — and tension — increase pace.

Again crowds assembled, chanting, threatening openly to riot, building tension, but again they were dispersed, albeit with slightly more difficulty.

Thus is was that the police faced Labor Day eve with some confidence that the beach crowd was controllable – and with a carefully prearranged plan of action in the event of more serious trouble.

But Labor Day eve was different. This time there was no particular build-up of tension. The crowd simply hung around and waited until 7:45 – then went into action as a body.

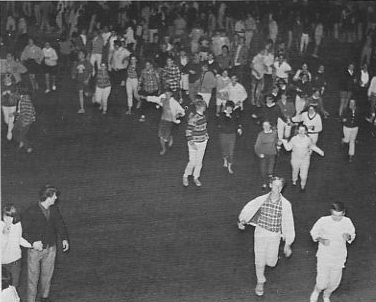

Once dark settled, hundreds of boys — and girls — raced

from beach to boulevard, some nervous, some exuberant.

They assembled on the beach; then one horde raced toward the Casino while others charged the police and fire stations a block inland from Ocean Boulevard. Only then did Police don steel helmets and bring out night sticks and the two dogs of the Hampton riot squad. With these, and ultimately with tear gas, police were able within about an hour to clear the central position of Ocean Boulevard and the beach, splitting the crowd and immobilizing small segments of it in the side streets. Thereafter for several more hours it was slow going as police pushed the divided crowd bit by bit to north and south. During this period the greatest damage was done – broken windows, and three small wooden beach buildings set afire. Ultimately when Maine State Police were brought in, the crowd was dispersed and/or driven across the bridge to Seabrook and ultimately into Massachusetts. Thereafter order was maintained with additional assistance from the New Hampshire National Guard.

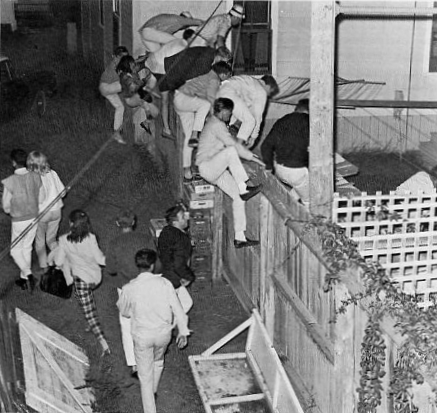

10:30 p.m. — trapped between side streets, youngsters

dodge through back yards.

Particularly in view of The Boston Globe and Boston Record American charges of police brutality, we feel obliged to note that Police discipline was on the whole above reproach. Particularly outstanding were the N.H. State Police. We saw them walk through a fusillade of rocks and sand-filled soft-drink cans without even looking in the direction of the crowds. One trooper walked through a bunch of exploding fire-crackers without breaking stride. The Hampton riot squad was equally effective.

We saw troopers and officers use dogs and night sticks and fists – and finally tear gas – to dispense an advancing wall of young people. Subsequently bird shot and rock salt were also employed.

Later in the night there were undoubtedly isolated cases of unnecessary force employed by police. But it should be considered that the rioters were also using force and plenty of it. There was scarcely an officer on duty that night who wasn’t struck by a flying missile. Several were badly injured. They were angry and tired (some State Police were on duty from 2:00 p.m. Saturday to 2:30 a.m. Sunday; then from 2:00 p.m. Sunday to 7:00 a.m. Monday). A persistent rumor of two dead police didn’t improve their frame of mind.

1:00 a.m. — Amphibious “Duck” with

Hampton police aboard patrons Beach.

It should also be considered that once the riot was proclaimed at 8:15 p.m. no unauthorized person was legally allowed on the street. The riot act is little different from martial law, and if the crowd didn’t know it, they learned it the hard way.

It was an ugly night, but it wasn’t as ugly as some of the newspapers painted it. Strangely, the worst offender was The Boston Globe, which subsequently carried several of the most penetrating analyses of the riots. But on September 8th a Globe story by Louis Kaufman read in part:

“No one who experienced the Labor Day weekend at Hampton Beach will ever forget it. It was ‘their’ sinking of The Titanic and ‘their’ London blitz all rolled into one . . . . Police clubs found skulls, and youth found and dropped police. Rocks sailed through windows and more wounded fell. The looters went to work . . . . Tear gas filled the air. Few in Hampton kept hands from burning eyes . . . . Hospitals were filled . . . .”

Further on Kaufman gave a melodramatic account of the drive to push the remaining rioters out of town. Several other Globe stories in the same issue wrung every drop of emotion possible from the Hampton scene, with much emphasis on police brutality and the boy who was shot in the eye.

Such overstatement by the press does little to help the town of Hampton understand its own problem, and – even worse – it serves as an open invitation to trouble makers for future years.

It is most important to note that Kaufman erred in one particular respect: there was virtually no looting associated with the Hampton Beach riot.

‘There were also no instances of assault by the rioters upon casual persons, nor rape.’

This is not to minimize the damage or disorder which ere certainly the worst in Hampton’s history. But if our goal is to analyze this particular riot, it is worth recording that no rape occurred, since this crime may be a part of more serious riots. On this same Labor Day weekend, for instance, when motorcycle gangs invaded Monterey, California, four men were arrested on rape charges and there were several robberies. When we have such a basis for comparison, we see that there was an ethic of sorts in the Hampton situation.

Hampton Police recognize this ethical limitation. “They could have ruined the Beach,” Lt. Paul Leavitt told us. “If they’d really wanted to, they could have burned the town. So far as I know, no attempt was actually made to set fire to the Casino. Most of the actual loss was in broken windows and other damage incidental to throwing rocks.”

It has been reported from several other sources that there was a restraining element which worked (with greater or lesser effectiveness) within the crowd itself when the damage became too vicious. Managing Editor Ray Brighton of The Portsmouth Herald recalls that when some youngsters were stoning a fire engine at work, others in the crowd were trying to restrain them, shouting, “Hey, knock it off! Not at the fire engine!”

One boy told us of an incident which occurred when a gang had begun to stone an Ocean Boulevard hotel. A boy from the hotel emerged and begged the rioters to stop which most of them were willing to do. Then when couple of toughs began to pummel the hotel boy, others from the crowd came to his rescue and released him.

The single most savage act of record was the throwing of “Molotov Cocktails” (gasoline bombs) at the amphibious vehicle in which Hampton Police were riding. Had one actually gone inside the vehicle and exploded, men might well have been killed. Obviously the restraining element of which we speak was not in force at this point. Fortunately for Hampton, this act was not wholly typical of the crowd.

Who, then, were these rioters? Where did they come from? Why did they behave as they did?

If we can accept the rough figure of 3,500 for the total number on the loose that night, it seems fairly safe to say that 2,500-3,000 of them were passive. They wanted to be on hand to enjoy the excitement, perhaps to flaunt authority, but either through timidity or conscience they refrained from direct action. Police and other observers generally agree to this analysis. These were the youngsters who made up the mass of the herd and who galloped about as they were exhorted by the leaders or pursued by police.

Look at the crowd from another aspect: How many were girls? Estimates vary from 40% to 50%. No girls were arrested, although some were observed to take part in the rock throwing. In general it can probably be assumed that the girls were not primarily the aggressors.

Still another breakdown of the crowd was attempted for us by several of the boys with whom se spoke. They felt that half to 75% of the total mob were the “regulars” at the beach – either summer residents, employees, or regular weekend visitors. They don’t deny that some of these regulars could have been crowd leaders, but they do draw a sharp distinction between regulars and the “hoody types from Massachusetts” who came specifically for the Labor Day weekend and specifically to make trouble. “You could spot them as soon as they turned up.” One boy told us. “They were no one we knew. All you had to do was look at them to tell they weren’t college types. Mostly they kept to themselves.”

To draw an exact line between the ‘hoody types’ and the followers is a dangerous and unnecessary exercise. Suffice to say that the toughs were a significant minority. Estimates vary from one boy’s guess of 75 to one policeman’s guess of over 300.

Between these activists and the passive mass, there was probably another group who were in and out of the forefront – not habitual troublemakers, but tough or aggressive enough to get into the fighting and rock throwing. “You get up front because you want to see,” said a boy, “and then you get involved yourself. The only time I threw anything was after my third dose of tear gas. I got so mad I finally picked up one of the tear gas bombs and heaved it back at the cops. I couldn’t even see. I had to get another guy to tell me which way to throw.”

Another boy would have been perfectly willing to storm the police station but wouldn’t have considered throwing rocks at private property.

It seems almost academic to point out that in trying to cope with attempted riots in the future we should consider that we must contend with two groups: a relatively small number of troublemakers and a relatively large number of followers.

Consider first the troublemakers. There is a division of opinion as to the thoroughness and effectiveness of their organization. One veteran observer feels sure that there was a massive plan of attack and the rehearsals for that plan were acted out in “dry runs” Sunday afternoon. The fact that the police captured three cheap citizens’ band radios and that “Molotov cocktails” were in evidence supports the theory that the planning was detailed.

The youngsters take the view that the planning was mostly haphazard. “One guy would jump up and say, “Let’s go,” and maybe some of us would start after him, but then if nothing happened we’d all come back to see what the next guy was going to do . . . . Nobody could have really led us. We were too disorganized.”

To remove the leaders from the crowd was obviously the primary aim of the police. Obviously also, it was a difficult task. The question remaining is whether it is possible to do the other way around — to divert the mass of the crowd from the leaders.

There are indications which suggest that this might work or that it might backfire. On the hopeful side, it now appears that a number of the regulars resented the intrusion of the hoody types. “This year there wasn’t the same feeling of kinship among he kids,” one boy told us. Several others felt that things were carried too far this year — but they’re still planning to come back next year to see what happens.

Another boy said, “We thought it was funny when the newspapers told about thousands of angry youths. We weren’t angry — we were having a ball!”

Thus it appears that if diversion is to be any part of the solution, it will have to be pretty absorbing. Even before we think of diversionary methods, we need to have more insight into the relatively passive youngsters’ motivation.

Their own answers shed some light: “Status symbol! What more exciting thing to talk about when you get back to school . . . . We go to tell the cops off. They push us around all the rest of the year. This is one night when we get to shove back.”

In part this seems to be continued resentment against the Hampton Police, but further questioning showed that it applied to police in general, to authority in general, and to the adult world. There also seems to be the feeling that Labor Day at Hampton Beach is the one night when it is not only possible to raise hell — despite riot laws, added police, and increased punishment — also a night when it can be done with a sort of sanction. To many of them it’s still a game.

In a further search for crowd motivation we took our questions to Dr. Stuart Palmer, criminologist, professor of sociology at UNH, author of such books as a Study of Murder and Understanding Other People.

He too stressed that the problem is complex and deep rooted and that the solution will come only after much close study.

“I think to blame the automobile is a superficial answer,” he told us. Sure – the automobile age has had something to do with splintering the family. But I doubt that it’s directly related to the riots. If the kids want a riot, they’ll get there, whatever the transportation.

“I think a more important physical factor is that there are simply more people. Hampton Beach has far more accommodations and much larger crowds than it did even ten years ago.

“I think there is truth in the statement that parents have abdicated their responsibility, but again this is only part of the problem. The parents themselves are ambivalent and frustrated. Our culture has become confused. There seem to be no firm guidelines. Adults are torn in two directions by such problems as human equality vs. human inequality, competition vs. cooperation. As more of our adults have risen in recent years from the laboring to the business classes, we have found ourselves caught in the conflict between the Puritan Christian ethic, especially here in New England, and the business ethic, which is much more predatory.

“Thus in our frustration we find it difficult to give clear guide lines to the young.

“Considering the political stability of the United States, we have a fairly violent society in terms of murder, assault, and other similar crimes. Here’s another ambivalence: we abhor violence, but we are fascinated by it.

“As an analogy, the French see no sense in American fascination with pin-ups — pictures of girls. Similarly, the Icelanders, for instance, fail to share our absorption with violence, murder stories, or automobile accidents.

“The young act out this violence in a kind of ritualism. Adolescence is a conflicted period. The adolescent doesn’t know whether he’s fish or fowl. This is frustrating. Frustration leads to aggression.

“Hampton is a kind of specific symbol for what the young people unconsciously feel is the cause of their frustration. Hampton has a reputation for wanting its clientele to come from the better elements of society. Here is something to rebel against — middle-class morality. Salisbury Beach doesn’t have the same image, nor Revere, nor Coney Island. It’s the nice beaches that are assailed — Ocean City, Ft. Lauderdale, Seaside, Oregon — and Hampton, New Hampshire.

“Parenthetically, I also think Hampton has unconsciously set up a self-fulfilling prophecy about its riots. People there say “when,” not “if.”

“I don’t think stricter punishment will be the answer, and it might increase the motivation for the young. The threat or fact of greater punishment increases the frustration. More frustration leads to greater violence. Eventually you reach the point where you have to club them over the head, which is possible but obviously not desirable.

“Considering the degree of violence that occurred at Hampton this year, I think that imported entertainment simply for Labor Day weekend might have failed. It’s probably too late now for that.

“I think there will be no clearcut, simple solution. The answers will have to come from study and experimentation by Hampton citizens to comprehend the problem in whatever way they can. The more citizens who participate, the better. When it’s a community problem, the solutions must come from the community. If the citizens don’t have a hand in formulating the solutions, they won’t believe in them themselves. Frequently such ventures fail because they are set up from the top. The leaders have preconceptions and go through the motions of discussion to arrive at these same preconceptions.

“Despite the fact that the deeper motivations for the riots are rooted in our culture, Hampton would make a mistake to shrug off the problem as an external one. There is, of course, a need to segregate the troublemakers, which can be a tough problem. Maybe youth civic groups would be effective. Possibly some sort of entertainment would make the troublemakers more visible. But it might be wise to experiment through the summer, to build a tradition of genuine concern for the young.”

And there, we would add, may be the germ of the answer — genuine concern for the young. So long as Hampton regards them as enemies, they remain so. If there can be genuine concern, solutions may follow.

We asked one boy who was in this year’s fracas if he felt that a youth civic group might help — if entertainment for young people would be effective.

“Maybe,” he said. “If it could be informal somehow, not just an excuse to contain us.”