By Amanda Milkovits, Staff Writer

Foster’s Sunday Citizen

Sunday Morning, September 12, 1999

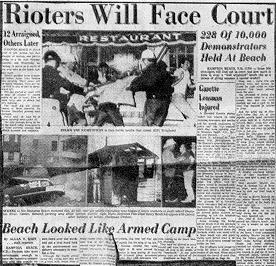

HAMPTON — On a night 35 years ago, Hampton Beach was a war zone.

Thousands of youths and young adults rioted in the streets, screaming “Kill the Pigs!” and “Burn the Casino!” as they tossed sand-filled bottles, smashed windows and burned down parking attendant booths. Steel-helmeted state troopers and police officers barreled through the horde with batons and firearms loaded with rock salt, as firefighters blasted fire hoses to push back the crowd. Local police narrowly missed being burned alive in their amphibious tank when a Molotov cocktail was launched at it. The National Guard set up machine-gun nests along Ocean Boulevard, and police hurled tear gas canisters at the mob bearing down on them. Dozens of people were injured; miraculously, no one was killed.

The backdrop was the nearly century-old resort beach, with its hotels, curiosity shops and seaside restaurants. But flames and fury ripped through the sky that Sunday night, Sept. 6, Labor Day weekend. Those who were there have never forgotten it. Nothing like it had ever occurred there before, and nothing like it has happened there since.

“At happy Hampton Beach, this seemed impossible,” Harold Fernald, a former Hampton special officer, said of that night.

There had been rumblings of trouble over the previous summers.

On Labor Day weekend in 1962, crowds of rowdy youths blocked traffic along the boulevard and formed a snake dance, causing police to call in reinforcements from all over the state.

Then came 1963. The Sunday of Labor Day weekend was again the scene of a fracas at Hampton Beach, when masses of people crowded the beach and boulevard, chanting slogans at police, setting trash baskets on fire and tossing firecrackers. When they surrounded a cruiser, police fought back with tear gas. After it ended by midnight, about 55 teen-agers had been arrested. Town officials cracked down on the beach by setting a summer ordinance that closed all restaurants from 1 to 6 a.m., and they asked for a state police barracks to be built at the beach.

Trouble was becoming a pattern at the beach on Labor Day weekend, and the town officials wanted it stopped. By April 1964, Selectmen Chairman Bob Danelson and the other selectmen drove to Concord to meet with Gov. John King to discuss controlling potential problems at the beach. They wanted the National Guard stationed there for the Labor Day weekend; he assured them that he’d dispatch those units.

But a week or so before Labor Day, King changed his mind. There wouldn’t be any National Guard. The town would have to take care of its problems. The selectmen wrote to Hampton’s state legislators, telling them of King’s decision and saying, “We want you to know if the riot gets bad or out of hand, we’ve done our part.”

They knew something was coming. There were rumors of flyers printed up all over the country, telling people to gather at Hampton Beach on Labor Day weekend and “Burn the Casino.” Beach business owners were skittish, and some beachgoers were becoming brazen.

But police learned much from the most unlikely sources – local troublemakers. The riot was being planned by “outsiders,” and these local kids didn’t appreciate outsiders stepping in on their turf, Fernald said.

That Sunday, all the town’s officers were called into work several hours early. They had already set up temporary structures near the police station to serve as makeshift jails, and they started blocking off roads into the beach. “We were ready for something,” Fernald said.

Most of the special police officers hired for the summer were like Fernald, teachers from the surrounding communities. Many were also military veterans, having served during World War II and the Korean conflict. Fernald believes that military training helped them keep their cool and stay organized during the riot.

Fernald and several other officers were posted outside the new police station on Ashworth Avenue; other groups of officers were stationed at various places all around the beach. They were armed with their batons, tear gas canisters, sidearms and rock salt. They knew, above all, that they had to stick together. If they were separated by the crowd, they could be killed.

The sun flickered from the sky, and dusk began to fall. On the beach, crowds were gathering. Peter Randall, author of “Hampton: A Century of Town and Beach,” wrote later that a teen-age boy rushed up to him, saying, “Be ready to go in 10 minutes.”

It was about 7:30 p.m. when Fernald heard them coming. “It sounded like a rolling crescendo of noise,” Fernald remembered. “I think they were shouting Riot! Riot! or Pigs! Pigs! – and they came running down. I can still see them when they came, jumping over the Casino fence.” There were thousands of them, flooding the Casino parking lot, side streets and racing toward the police station. But Fire Chief Perley George was ready for them. All the fire trucks were lined up outside the nearby fire station, and when the crowd came, firefighters blasted the fire hoses to keep them back – as police tossed canisters of tear gas. Meanwhile, Fernald’s wife was back at home in downtown Hampton, listening to radio broadcasts of the riot and hearing what sounded like gunshots.

That’s when Bob Danelson drove down from his Moulton Road home to the beach. He saw the mob being pushed back by the fire hoses and police. One of the officers yelled at him as he pulled his car over: “What’s the matter? Are you out of your mind? You could get killed!” Then he recognized Danelson and waved him on to the police station. That was the headquarters – and the scene of attack. All the selectmen gathered there and made their way over to the Casino as police battled the rioters toward the sand and water. The Route 1A bridge was blocked off and the drawbridge was raised. Seabrook police were on one side, keeping rioters away from the bridge and pushing the others toward the middle. On the other side were the troopers and local police, shoving the rioters off the bridge and into the Hampton River. Below, boatloads of rioters were trying to cross from Seabrook to Hampton to join the fray, Fernald said. And on the sidelines, particularly along the Casino, were some locals who’d come to gawk. “It was a mass of screaming humanity,” he said.

Out on the corner of Landing Road and the expressway, Hampton Officer John Donaldson was trying to direct traffic away from the beach. His was one of several blockades meant to keep people from the beach.

“You could see it building and building,” Donaldson said. “For the most part, it was a kind of hoorah sort of thing. There was an anonymity in crowd behavior. They would do things they wouldn’t do as an individual.” People were trying to get into the beach – to riot, to watch the scene, or to check on their beach property. And terrified people were trying to get out.

A car zoomed past Donaldson and he stepped back, into the path of a car driven by a frightened elderly man. “I kind of lost interest in the riot then,” Donaldson said wryly.

He was loaded onto a stretcher by young Officer Robie Beckman and sent to Exeter Hospital. Beckman would join Donaldson there later that night, after a rioter smashed his face with a rock, leaving the officer needing 29 stitches.

“Things were pretty bad,” Danelson said.

Dozens of rioters and police were injured by flying glass, rocks and bird shot. One boy was hurled through the plate-glass windows at the new Chamber of Commerce building. Another 16-year-old boy lost sight in one eye after he was hit by a spray of rock salt and bird shot.

Every one of the windows of the new McCoy’s Restaurant was smashed out and the inside was looted. The owners were huddled inside, terrified and devastated as they helplessly watched their restaurant being destroyed. Some of the troopers became separated by the crowd and were badly beaten, Fernald said. He and his group of officers were pelted with bottles and rocks. When police drove the town’s amphibious “duck” vehicle on Ashworth Avenue, someone tossed a Molotov cocktail at them.

“If they had been really armed with weapons, we would have bit the dust,” Fernald said.

Police were arresting rioters and tossing them by the hundreds into the temporary jails. Fires raged in the two parking attendant booths and broken glass littered the roadway. Even the firefighters were armed with shotguns.

“Anyone down there, their lives were threatened,” Danelson said.

The riot had been raging for nearly three hours when the selectmen headed back to the police station. Col. John Regan of the New Hampshire State Police called Danelson and begged him to get the National Guard on the scene. Danelson didn’t waste time. He got on the phone at the police station and called the governor’s office, reaching King’s right-hand man (the governor was at a Labor Day social function).

“I can still see him almost begging the governor to get the troops in here,” Fernald said. “I felt like talking to the governor myself. I was watching Bob’s face. I’d never seen Bob so mad.”

But the governor’s assistant told Danelson that he wanted to hear from State Police first. So, Regan called back. Danelson overheard him. “He said, ‘They’re tearing this beach apart, throwing bombs, breaking windows and almost killing people!'” Danelson said.

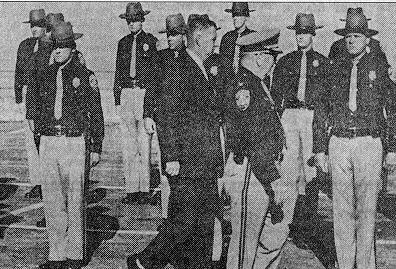

The governor called in the National Guard units, which arrived at the beach at around 2 a.m., hours after the riot had started. “They might as well have stayed home,” said an exasperated Danelson.

They stationed machine guns at various points along Ocean Boulevard and initiated martial law. Local police were ordered to turn in their ammunition. Fernald remembers the officers walking in the front of the station and turning over the ammunition – and walking out the back door, where a sergeant handed the equipment back to them.

“You can’t send men out into a situation like that without it,” Fernald said emphatically.

The governor arrived, still dressed in his tuxedo, to survey the damage and to swear the local officers into the National Guard. But Danelson couldn’t forget that King had reneged on his promise for help.

Fernald was assigned to drive around to the National Guard units to bring them food. All of the windows of his cruiser had been smashed out. He drove past burning buildings, broken glass and rubble and utter chaos.

“It was very difficult to comprehend that people would do things like that,” he said.

By dawn, the riot was over. The temporary jail was packed with youths and young adults, awaiting bail from their parents. Lawyers, too, circled outside the jail.

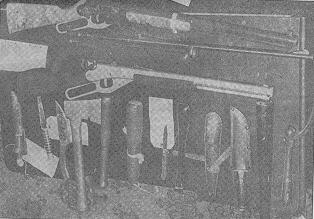

Hampton Beach wasn’t always the peaceful place it is now. This photo shows an assortment of weapons, including clubs weighted with lead, knives, hatchets and guns, that were collected during the summer of 1964. During the riot, a popular weapon was the beer can missile, consisting of an empty beer can filled with beach sand.

About 250 police from Maine, New Hampshire and Massachusetts had battled back the mob of an estimated 10,000. Out of the hundreds who were arrested, just 150 would face charges. Those who faced Hampton District Court Judge John Perkins found little mercy. He issued jail sentences of up to nine months and fines of up to $500. Most of the youths were from Massachusetts and New Hampshire cities far from the Seacoast; none were from Hampton.

Business owners were faced with rebuilding. For some, it took “weeks,” Danelson said. “And to rebuild things that were burned down and smashed, it took months.”

The riot of ’64 was not repeated in 1965. The weather was cold and rainy, Fernald remembered. The beach saw just 5 percent of its usual Labor Day weekend business that Sunday, although nearby Salisbury, Mass., had plenty of beachgoers, according to news reports.

And townspeople wanted to be sure it would never happen again at their beach. The Chamber of Commerce received a $40,000 federal grant from the Department of Heath, Education and Welfare to interview some of the rioters and try to define a cause for youth disturbances. Authorities from Tufts University, the University of New Hampshire and Harvard were called in. They found from interviews with more than 50 of the rioters that most were average youths from all class levels. Some were angry about high prices at the beach or the way they felt police and businesses treated them. Only a handful came to the beach ready to riot; others said they were there and they got caught up in it.

Fernald arrested one young woman that night who later became a teacher at Winnacunnet High School. “She said it was the thing to do, but once it got started, they got caught up in it and they couldn’t get out when it turned serious.” Fernald swears he saw people walking around the outskirts, carrying walkie-talkies and directing the riot. He suspected they were Communist organizers. However, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover later told the Associated Press that the riots in Hampton and other Northern cities had nothing to do with racial tensions or Communists. Instead, Hoover said, the riots were “a senseless attack on all constituted authority without purpose or object.”

But Fernald still believes that the 1964 riot was “a training ground” for others, including Watts. “We never caught the ringleaders,” he said. “They just faded into the crowd.”

Beach residents and youths also formed CAVE (Committee Against Violent Eruptions), a program meant to organize activities for youths.

These events were often poorly attended. Blame it on the struggles among the town leaders, including the chamber of commerce, which caused events to be canceled and rescheduled. Perhaps the programs weren’t particularly attractive to 1960s youths – with jug bands, and folk and minstrel music. No rock ‘n’ roll, said the town leaders, and Casino Ballroom owner John Dineen particularly didn’t want dancing because it would compete with his business. By the late ’60s, the CAVE program petered out. The shed where CAVE members met was eventually moved off the beach to Tuck Field, where it’s used for storage by the Hampton Youth Association.

After the riots, Hampton police underwent sensitivity training for handling youths and dealing with the public. Those policies hold true today, said Police Chief William Wrenn.

“I don’t think there’s the potential for (riots) today because our whole way of policing is much different than it was in the ’60s,” he said.

Back then, police were very reactive, waiting for a crime and then pouncing on the offenders quickly, he said. Now, police work within the community to learn of problems before they build.

“We understand people are here to enjoy themselves and have a good time, and we are here to help them to do that, because this is a tourist community,” Wrenn said. Times have changed. Bathing suits that would have shocked people in 1964 now elicit shrugs. Bongo and guitar players attract small, mellow crowds, and no police presence. The rock ‘n’ roll once prohibited at beach parties is now played by bands at the Seashell Stage – as golden oldies.

“These crazy kids are now 50-60 years old, and they’re probably thinking about what they did,” Danelson said.