HAMPTON: A CENTURY OF TOWN AND BEACH, 1888-1988

Chapter 21 — Part 1

Back to previous chapter — Forward to next section — Return to Table of Contents

By Richard N. Livingstone

Building for Education

The history of education in Hampton since 1888 is the story of the buildings in which this education took place, just as it is the story of the content of the education itself and the people who gave this education. It is also the story of how a town’s educational process, far from being set apart from the rest of society, mirrors that society, reflecting the events and perceptions as well as the preoccupations and passions of the people and the society of which they are inevitably a part.

Formal education began in Hampton — as it began and continued for a long time elsewhere — in the home. Then it moved to what were known as “district schools,” usually one-room buildings. The district schools, of which Hampton at one point had six, were run by “prudential committees.”

Describing these schools, Reverend Roland D. Sawyer noted that each year they returned a surplus from the money appropriated to run them. Some years there was more of a surplus than usual — when, for example, a committee had managed to pay only $3.50 instead of $5 for a cord of wood.

However, in 1885, the New Hampshire Legislature had voted to end district schools. (Nevertheless, it was not until the Centre School was built in 1921-22, replacing all the one-room district elementary schools in Hampton, that the district schools disappeared.) At this time, one grammar school was established for the town, along with what primary schools were thought necessary.

The existing schools in Hampton in the late 1800s were the Grammar School, a two-story wooden building on the site of what became Centre School; North Primary, East Primary, West Primary (closed and then reopened in 1903), and Center Primary (located in the Grammar School); and Hampton Academy and High School (now Hampton Academy Junior High School).

In 1887, there were 135 pupils enrolled in the primary schools and 67 in the academy (that year, the total school revenue raised and spent was $1,800). At that time, Hampton’s school population was slightly higher than what it had been 100 years earlier. It was reported, eight years later, that Hampton had no more schoolchildren than it had had 120 years earlier, in 1775, “when her population was but 862.” This quiescent state of the population no doubt reflected the continuing move to the large cities during the Industrial Revolution as well as the continued migration westward.

Of the schools in Hampton, the most historic was on the site of what later became known as the Centre School. The first school-house had been built on this site only 29 years after the Pilgrims had landed in Plymouth, in 1649. A plaque on the grounds of the Centre School marks the approximate site of that “First Public School in New Hampshire — May 31, 1649.” In 1712, another schoolhouse (perhaps the first one was torn down or burned down) was built on the same site on which the Centre School now stands.

Later, the Centre School site was occupied by what was called the “Old Grammar School.” Pupils attended this school for grades 1 through 3 (downstairs). Then they went to the East End (or Intermediate) School, on the corner of Winnacunnet and Locke roads, for grades 4 through 5. Next, pupils returned to the Grammar School (upstairs) for grades 6 through 8, and finally, grades 9 through 12 at the Hampton Academy and High School.

Whether called by its new name, Hampton Academy Junior High School, or its old name, the academy ranks as one of the oldest educational institutions in New Hampshire. Incorporated June 16, 1810, as a privately endowed coeducational school on the secondary level, it was known first as The Proprietary School. Its site was the Meeting House Green — which later became “Academy Green” when a new meeting house was erected elsewhere.

In 1821, The Proprietary School was incorporated as Hampton Academy with a board of 13 trustees. On August 29, 1851, the school building burned to the ground, and a second and larger building was erected the next year.

On January 22, 1883, this building was moved nearer the center of town, to a lot across from the cemetery. The moving day was a town holiday, accompanied by the ringing of bells in the town’s two churches. Placed on long cut-and-peeled trees, which acted as the runners, the building was pulled by 160 yoked oxen and 20 heavy horses.

The teams were hitched in four lines instead of two, a double line on each tree skid. At 12:30, the team began its quarter-mile uphill journey, over a snow-covered road, and just 17 minutes later reached the spot near the corner of Academy Avenue and High Street. The one-inch heavy chain cable, borrowed from the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, had not a link broken.

On June 17, 1910, a memorial boulder with two plaques was dedicated at the historic site on the Academy Green from which the Hampton Academy building was moved that day. The Hampton Academy Alumni Association took on this project for the centennial of Hampton Academy, with the dedication taking place in conjunction with the association’s fourth annual meeting.

On September 14, 1885, almost three years after the move, Hampton Academy and High School opened as a free high school. The children of Hampton and surrounding towns, however, continued to attend high school here as tuition pupils, with their tuition paid by the Town.

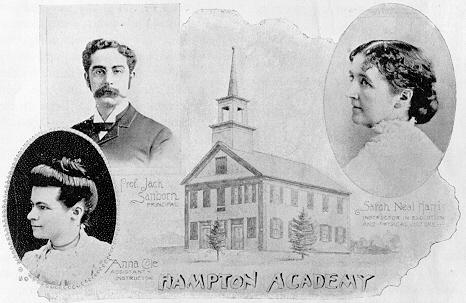

Principal Jack Sanborn of Hampton Academy

with teachers Anna [May] Cole and Sarah Neal Harris.

Composite from The Granite Monthly, July 1896.

Succeeding years saw a gradual change in the makeup of Hampton’s elementary schools. But many of the events during the last of the nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth had a somewhat familiar ring. In 1914, townspeople were discussing whether or not to buy the shoe shop and convert it to a school. A year later, the central schoolhouse committee recommended the construction of a six-room school to meet the needs of 240 students, but it was voted to postpone indefinitely any action. At the same time, the article to buy land for a new school was tabled. In 1916, Superintendent Morrison of the State Department of Education strongly recommended that Hampton improve its school buildings, and at the very least build a new Village school.

At the school meeting on February 22, 1917, it was voted to postpone indefinitely the article relating to a new schoolhouse, as well as one to buy a piece of land for the school, because of the “uncertain international situation.” The new school seemed far away.

But while sometimes slow to act, Hampton did so in the end. Four years later, in May 1921, an adjourned school meeting voted to build a new two-story brick school, to be called the Centre School, on the site of the “Old Grammar School.”

In March 1922, the new $90,000 school was dedicated, with the Hampton Male Quartet singing and James N. Pringle, deputy commissioner of education, speaking. The committee for the school consisted of L.C. Ring, chairman; George Ashworth, secretary; Harry Munsey, treasurer; Edwin L. Batchelder; and Christopher S. Toppan.

The opening of the new school enabled the town to close the East End, or Intermediate School. At the same time, the “Old Grammar School” (on what is now the Centre School site) was moved to the corner of Beach Road (now Winnacunnet Road) and Academy Avenue and converted into a firehouse and courthouse. The freshman class of the academy occupied the Centre School from the fall of 1922 to the fall of 1940, when the new academy building opened.

In May 1923, the Hampton Union reported, Frank S. Mason bought the old North School, with plans to move it to Highland Avenue to convert it to a dwelling. [Ed. note: This school building actually became the second story of a dwelling at 44-46 Dearborn Avenue.]

Then, beginning in 1940, came significant change. That year, the school district took over and built a new Hampton Academy building, a three-story addition on the north side of the old wooden building, at a cost of $114,000. It was designed to replace the old academy structure. The new building was dedicated June 8, 1940; at the ceremonies, Selectman Edward S. Batchelder, chairman of the Building Committee, turned the keys over to 0. Raymond Garland, chairman of the School Board. (The next month, the 1852 academy building was sold at auction for $200 to a Newburyport wrecking and salvage company and was razed that August; on the same day, Hampton’s East End School House was auctioned off for $120.)

In September 1941, the Hampton school system had 291 students, the largest number in the history of the school system. In 1946, Hampton Academy and High School graduated 36 pupils, the largest class ever to graduate from the school. In the annual school report for 1947, the superintendent of schools, Roy W. Gillmore, hinted at what was likely to come. He cited the increase in the number of pupils in the 10 years from September 1937 to 1947 — 370 to 538.

But, in a statement that presaged what later generations called the “baby boom,” the superintendent declared that “the increase in enrollment is not temporary.” National surveys, he went on to say, showed that the birth rate in the United States increased from 18 per thousand annually in the prewar period to 26.2 per thousand in 1947. The need for additional schools was, he said, “definite.”

In the year ending in 1948, the superintendent used in his report a word townspeople were not yet used to hearing. That word was overcrowding, a term that would, to the dismay and even despair of taxpayers, persist in the years immediately ahead. The next year, the phrase increasing enrollment appeared in the annual report.

The headmaster of Hampton Academy and High School said that overcrowding was becoming “more acute.” A survey recommended purchase of additional land for both the Centre School and the High School, the immediate addition of elementary school classrooms and special facilities to the Centre School, and the later addition of classrooms to the High School.

During the late 1940s, the number of pupils enrolled continued to mount. In 1948, the number of pupils enrolled in September in the first three grades stood at 105. The next year, that figure rose to 138. In 1950, the number enrolled in those grades rose to 150. That same year, a record school budget, $133,447.23, faced Hampton voters. That year also saw a six-room addition and alterations to the Centre School.

The discussion of increased enrollments and expansion continued. The report for 1952 noted that, “based on present figures, it seems reasonable to believe that Hampton faces a sizable increase in the immediate future.” That year began with kindergarten and grades 1 through 8 housed in the Centre School. Proposed solutions included construction of a junior high school.

The dominant school issue in Hampton in 1955 was the proposed construction of an $220,000 “campus-type” elementary school. At a special school meeting on November 26 the previous year, the building of such a school had been authorized by a two-vote margin. In the end, this vote was rescinded by a vote of 334-294 at a meeting attended by a record number (700) of townspeople.

One of the solutions to overcrowding carried out that year was to use the Congregational Church chapel for a third-grade classroom.

In 1955, it was proposed to build a new elementary school off High Street between Mill and Hobbs roads. At a special school district meeting on April 27, 1955, voters authorized the School Board to name the new school “The Adeline C. Marston Elementary School,” after one of Hampton’s most beloved teachers.

For a long time, many on the seacoast had felt that the area needed a new high school. As early as 1937, a committee appointed at the school meeting drafted a bill for the Legislature to give the Town the right to issue bonds, up to the amount of $200,000, to build such a school. But now, what Dr. Harold Pierson, a Winnacunnet School Board member from Hampton, described as “explosive growth patterns affecting the entire Seacoast Region,” began to emerge.

Only one of the seven school districts in Supervisory Union 21 had a high school — namely, Hampton Academy and High School. But, said Dr. Pierson, the “need for additional space to educate Seacoast students on the secondary level has become acute.”

During the early 1950s, Roy W. Gillmore, then superintendent of Supervisory Union 21, was “quietly planting the seeds” for a cooperative secondary school. In 1956, the seven school committees of Supervisory Union 21, meeting as a union committee, voted to set up a study committee to examine the possibility of forming a cooperative school district — or what would become Winnacunnet Cooperative School District.

Spearheading the drive to build the new high school was Superintendent Gillmore and later, after Gillmore retired in 1956, his successor, Dr. Edward C. Manning. Dr. Manning’s “dynamic leadership,” said Dr. Pierson, “was one of the most important factors in creating the cooperative district.”

On March 28, 1957, at an organizational meeting, the citizens of the four towns of the Winnacunnet Cooperative School District — Hampton, North Hampton, Hampton Falls, and Seabrook — voted 307-17 to form a cooperative and elected a school board of five members. On July 1, the voters approved the purchase of a 52-acre site on Landing Road in Hampton, and, by a vote of 85-2, authorized the borrowing of $1.3 million to build a high school building.

To be sited in Hampton, the $1.3 million school would be New Hampshire’s first regional high school. It was designed to accommodate between 600 and 700 pupils and to be ready for use in September 1958. Groundbreaking ceremonies were held October 30, 1957, and a little less than a year later, on October 26, 1958, the Winnacunnet High School was dedicated. Or, as the Hampton Union and the Rockingham County Gazette put it, “from cow pasture to a complete regional high school plant in slightly less than a year….”

An estimated 1,200 people attended the exercises, at which Governor Lane Dwinell and Dr. William G. Saltonstall gave the principal speeches.

The school just narrowly missed being dubbed Seacoast High School. The name had been selected from several proposed, and in the end, Winnacunnet — the Indian name for “The Beautiful Place of Pines,” as well as the name of the town of Hampton for its first year — won out by a vote of 64-60.

The opening of Winnacunnet High School also marked what Hampton Academy and High School Principal Bruce Russell termed “the end of an era in secondary education in Hampton. I believe,” he added, “Hampton Academy and High School has served the community well. It has met the educational needs of the youth in this area in an adequate manner. Our graduates have gone out to take positions or have continued their education in many post-secondary institutions.”

On June 13, 1958, while construction of the new high school continued apace, the academy held graduation ceremonies for the 42 members of the Class of 1958 and, with the last high schoolers gone, “the 148-year history of Hampton Academy as a secondary school came to a close.” Hampton Academy and High School became Hampton Academy Junior High School.

In 1961, by 176-35, voters approved a $475,000 bond issue to finance a two-story (and basement) addition to Hampton Academy Junior High School. On May 14, 1963, the addition was dedicated. The new addition, on the south side of the existing building and on the site of the old wooden building, added 13 classrooms to nine existing rooms in the original part of the building, as well as a library, music room, a girls’ locker room, a girls’ gym, and a “cafetorium” with stage.

The school would, it was announced in the 1964 annual report, continue for the time being to house pupils in grades 5 and 6, to share facilities with grades 7 and 8. When the new high school was built, the seventh and eighth grades, previously at Centre School, had been moved into the academy building.

Beginning in the late 1960s, the anti-spending mood began to grow. This financial pullback coincided with a rise in school enrollments. Since 1969, according to a report from the Supervisory Union 21 office, student enrollment in the entire union had slowly climbed each year until the 1975-76 school year, at which time it had showed a total of 4,296 students. (The union consisted of the school boards of seven seacoast towns — namely, Hampton, Hampton Falls, North Hampton, and Seabrook — the Winnacunnet Cooperative School District — plus South Hampton, Rye, and New Castle.)

In late 1969, the Hampton Union was running articles on the overcrowding of Hampton schools, especially in the Centre School, where “69 pupils are being taught in two small classrooms.”

The overcrowding was also evident at Winnacunnet High School. The school had opened its doors in the fall of 1958 to 474 students. By September 1967, its enrollment had increased from under 600 to 921, with an enrollment of 1,102 persons projected for 1970. However, an expansion in the mid-1960s had helped. This had produced three additions to the high school, including a two-story classroom wing with 20 general-purpose classrooms; an addition to the home economics wing; girls’ shower and locker facilities; and a new physical education room.

These additions had all been ready by the fall of 1965. At the same time, voters of the Winnacunnet Cooperative School District had approved a $75,000 three-room addition to the industrial arts department of the high school and $40,000 for expansion of the athletic field.

But it was the elementary schools that bore the brunt of the overcrowding and lack of space. In 1966, voters had rejected an addition to the Adeline C. Marston Elementary School, on which the continuation of kindergarten in Hampton hinged, by a three-vote margin. (Later in that year, however, townspeople did give almost unanimous support to the town’s kindergarten program, which at that point had more than 200 children.)

In 1969, study committees recommended construction of a new schoolhouse, but in April 1970, voters turned down a proposal for a new $1.1 million “open concept” elementary school; taxpayers, according to one newspaper report, were concerned with an estimated $10 increase in the 1970 tax rate.

In 1970, there was discussion of a site on Towle Farm Road for a proposed new school; and in June 1971, the Hampton School Building Committee voted 7-3 to approve the Towle Farm Road property as the site of a future elementary school. The alternative had been to build onto Marston. In March 1971, by a vote of 7-5, in a move that aroused considerable controversy, the Hampton Municipal Budget Committee killed a $1.7 million school proposal for a new elementary school.

Then, in March 1972, voters rejected a proposed $2.2 million middle school. This was the third defeat in three years for a new elementary school for Hampton. The next year, on April 11, 1973, on a vote of 729 yes and 677 no, with 937 needed to pass, and for the fourth year in a row, Hampton voters defeated a school bond issue.

By the fall of 1972, the results of this procrastination had become evident — double sessions were instituted for grades 5 through 8. Thus began a painful period for many parents, and what one observer called “a nightmare for students and teachers.” With double sessions, the kids were, as one educator put it, “short-changed.” Six Hampton Academy Junior High teachers met with the Hampton School Board, and, according to the Hampton Union, described double sessions as being “detrimental both emotionally and psychologically to the child.”

In December 1973, by a 3-1 vote, the Hampton School Board voted to stop double sessions for grades 5 through 8 at the Hampton Academy, with the double sessions slated to end January 28, 1974. The double sessions were to be ended by compacting the fifth grade from seven to six classrooms, changing the third grade at Marston School from five to four sections, changing the fourth grade at Marston from five to four classes, converting the nurse’s office at Hampton Academy into a classroom, compacting the sixth grade at the academy from six to five sections, and transferring the special-education class from the academy to the Centre School.

Now the tide had turned, and Hampton, though sometimes slow to act, had recognized what was in the best interest of the town and its children. In March 1974, by a 398-106 vote, townspeople approved a school bond issue for construction of a 10-room addition to the Hampton Academy Junior High School, ending the five-year struggle by school officials.

At the same time, the increase in enrollments had begun to affect Winnacunnet High School. In late 1974, the School Board voted to move to staggered sessions at the high school in 1975.

By 1976, however, Hampton’s school population had leveled off. And since that year, according to Supervisory Union figures, there has been a decline each year, at a rate of about 130 students a year.

The crisis had passed. Birthrates in Hampton, as elsewhere in the country, continued to decline, so it seemed likely that it would be many years, if ever, before the number of schoolchildren in the town would tax the capacity of the facilities for educating them. The problem would be, as in other towns and states, to find new uses for public schools that once served a growing population of young children.

Despite these longer-term trends, however, overcrowding in Hampton schools continued. Late in 1982, Hampton Academy Junior High School Principal Richard Annis put the 300 students in the seventh and eighth grades at the academy on “modified restriction.” The action followed assaults, the arrest of three students for smoking marijuana, widespread cigarette smoking on school grounds, and other incidents. Class size at the time was close to 30 students, which Hampton School Board member Jane Walker labeled as “dangerously high” for a junior high school.