HAMPTON: A CENTURY OF TOWN AND BEACH, 1888-1988

Chapter 3 — Part 1

Back to previous chapter — Forward to next section — Return to Table of Contents

Breakwaters, White Rocks Island,

and Hampton Beach State Park

1927-1949

Although the Town-owned trolley went out of business at the end of 1926, Henry Ford’s economical automobiles were available to nearly everyone, and Hampton and the Beach looked forward to ever-increasing business and growth. Modern hotels had replaced those burned in the 1921 fire, the Casino had new and vigorous ownership, the Beach Precinct had its own well-equipped fire department, and the Chamber of Commerce was proclaiming the Beach’s virtues throughout the East Coast and northward to Canada. As a mature resort, Hampton Beach was smug in its belief that it was providing clean, wholesome recreation — unlike Salisbury, Revere, and Old Orchard beaches with their noisy amusement parks and rowdy forms of entertainment. Hampton Beach was not without its problems, however, and, during this era came great changes that continue to have an impact on the town today. In a series of Union articles in 1957, James Tucker reviewed the Warren Manning Plan, which was to have a great effect on the Beach from the time it was presented until today. Tucker described the Beach of the early 1930s thus:

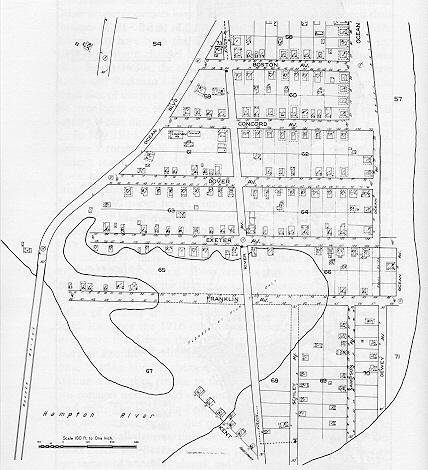

Hampton Beach … was in a pretty dilapidated condition as far as its physical aspects were concerned …it had been battered over the years by storms and tides to such an extent that practically one hundred acres in the White [Rocks] Island section had been washed away. Streets in the eroded area — Sampson, Dewey, Schley, etc., all named after Spanish-American War heros — had been lighted, equipped with water mains and sanitary sewers, and they were lined with summer cottages. Now they had all been obliterated. The overall loss was never estimated, but it must have been in excess of half a million dollars.

To support its requests for Hampton Beach improvements, the Hampton Beach Precinct hired engineer and planner Warren Manning to study the Beach and to make recommendations. His December 1932 report, issued by the Hampton Beach Development Commission, called for many changes, and, remarkably, a number of his suggestions have been acted upon. In summary, Manning outlined four areas of action. For Hampton River, he saw the need for jetties, to stabilize the river channel, to fill the area lost by erosion, to dredge the harbor, and construct a new bridge. His suggestion of filling the marsh for housing and an airport has failed to gather enough support for completion. For the beachfront, Manning called for new breakwaters, a wider boulevard, construction of boardwalks, and a music concourse with a band shell in front of the Casino; all of which have been built. His suggestions for the beautification of the entire boulevard with lawns and gardens and a recreational park between the Casino and Haverhill Street have not been carried out. Manning’s ideas for the main beach entrance included a new road from the west and parking lots west of the main beach. New north-south roads west of the Beach and a parkway along the entire New Hampshire coast remain as ideas. His fourth area, modernization, called for proper beach zoning and building codes, a new sewage treatment system, and a campaign to plant trees and flowering shrubs.

Although never officially adopted by the Town or the State, Manning’s plan did lay out in detail the steps many Beach and Village people felt would be vital to the future of the resort. Now, 50 years later, some of Manning’s ideas have changed the Beach.

One subject became the catalyst for the immediate changes: erosion. Hampton Beach is a barrier island, a long sand dune that developed over thousands of years in coordination with, and as a protection for, the marshes of Hampton River. This large sand dune was, and still is, unstable. Its sands come and go with storms and the seasons, but before people attempted to build upon the long dune, no one paid any attention to the changing contours of the beachfront. Even with the development of the main beach, there was little reason for concern, since the early Beach buildings were constructed behind an oceanfront dune that buffered the action of storms. These shoreline dunes were gradually destroyed, mainly by Town action, to make roads, parking lots, and house sites. Without the dunes as protection, the ocean began to intrude on the manmade beach, causing thousands of dollars of destruction. Breakwaters were needed to hold back the sea, and, when the Town was unable to round up the funds necessary to combat the impact of storms, the decision was made reluctantly to give up the beachfront to the state of New Hampshire in exchange for the protection.

Among the first dollars ever spent by the local government at the Beach was a total of $2.25 paid to William E. Lane for work at the Logs in 1882 and 1883, and $13.50 paid to “Charles A. Ross” in 1884 and 1885 for “making snow paths and clearing road at the ‘Logs,”’ that narrow section of land just north of Great Boar’s Head. The term may refer to some sort of breakwater built there to protect the rough roadway from the end of Winnacunnet Road to the south beach. In 1895, the Town spent $614.34 for “breakwater at the beach,” the first mention of the subject in the town reports — just the beginning of an effort that was to cost the Town many thousands of dollars until the 1930s. This first formal breakwater, built between Cutler’s and Boar’s Head, was some 800 feet long and consisted of stout 12-foot oak posts that were embedded 6 feet deep, inclined at an angle from the sea, and braced with timbers. Railroad ties were laid on the posts and covered first with rocks and then gravel to make a sidewalk. The following year, the town meeting appropriated another $500 for a 400-foot breakwater at the Logs, where the road was doubled in width and the telephone poles were moved from the east to the west side of the road. In 1898, another breakwater, perhaps an extension of the first, was built at a cost of $1,067, and another $780 was spent on breakwater repairs in 1901.

Although the Town spent a few hundred dollars over the next decade, the breakwater situation became serious in 1910. A winter storm had badly damaged the breakwater, and engineer William T. Ross was hired to make repairs using concrete and rocks. The State apparently provided some money, and a total of $1,000 was spent. The following year, the Town spent $2,200 more for breakwater repairs and a concrete sidewalk, and also appointed a committee of Judge Thomas Leavitt, John G. Cutler, and E. G. Cole to go to Concord to seek more state funding. As a result, Governor Robert Bass and the Executive Council visited the Beach in May to view the work the Town had done on the boulevard and the breakwater, but the town report does not indicate that state money was provided for additional work.

An August 1912 Merrill H. Browne Hampton Union letter indicates that the effort to get state money had failed, and he suggested asking the Legislature for funds. The state road north of Boar’s Head was in danger of washing away, he said, and with the Town planning to lease hundreds of lots in the area, protection was needed.

In 1913, the Union reported that the breakwater was extended 150 feet south of the Casino, which “protects the sea from washing away sand and makes a fine promenade.” All previous work on the breakwater had been done from the bandstand northward. Across the street from the Casino, the old wooden boardwalk was pulled up and a concrete walk was built.

Work on three breakwaters was underway in May 1914 under the direction of Selectman Joseph B. Brown — one built in the Pines section and two others running 500 feet north and 500 feet south of the Casino. After a September meeting with Town officials and the Hampton Beach Improvement Company, plans were announced to extend the wall eventually from Boar’s Head to White Island. At that time, the seawall protected the beach from the Ashworth to the Hill Crest. The wall was built 22 feet above the high-water mark to allow plenty of room for bathers. When finished in two years, the project would include a promenade with electric lights. In April 1915, the Legislature voted $5,000 for the breakwater, which, when added to the Town’s $2,000, extended the seawall and walk from opposite Cutler’s to the Pelham. Electric lights were also installed along the wall.

James Tucker remembered that during the summer of 1915 there was no erosion problem along the beach. As he wrote in the April 16, 1953, edition of the Union, “There was three or four hundred feet of sand between the east side of the boulevard and the mean high tide mark. This happy condition obtained along the entire main beach northward to nearly Cutler’s Sea View Hotel. And even in the small cove in front of Cutler’s, there was a small but excellent bathing beach. In the business section, all of the larger hotels laid board walks on the soft sand opposite their places of business in order that their patrons might more easily walk from the boulevard east to the hard sands of the bathing beach.”

Between 1916 and 1919, the Town appropriated another $11,000 for breakwaters, but more work apparently was needed, because the 1920 town meeting voted to spent $4,000 annually over the following five years for work on breakwaters. At an adjourned 1923 town meeting, voters continued to support breakwater construction, appropriating another $10,000. In May 1926, at the third annual Precinct banquet, Governor John Winant opposed spending a requested $20,000 in state aid for the breakwater, saying it wasn’t enough to do the job, and he called for federal action to do the work.

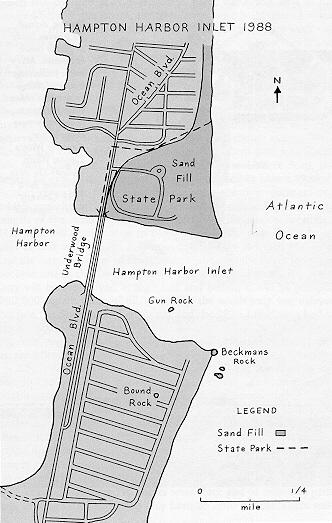

The unstable character of this barrier island is best explained in the story of White Rocks Island, once a major Hampton Beach development, now vanished under Hampton River. White Rocks Island was first just the rocks, a ledge outcrop off the mouth of Hampton River. To find the rocks today, it is necessary to look across the river from Hampton Beach State Park to the easternmost point of land on the south side of the river. Southwest of this rocky outcrop, and now surrounded by houses, is Bound Rock, the boundary between Hampton and Seabrook. For most of Hampton’s recorded history, both White Rocks and Bound Rock were located in the middle, or to one side or the other, of the river. Offshore currents, storms, and tidal action have caused the erosion and deposition of sands, resulting in the shifting of the channel of Hampton River. (The name “White Rocks” comes either from the whitish color of these rocks or from the story of a Captain White who was shipwrecked on the island, built a tent from the sails, and with his crew salvaged the cargo of lumber from the ship.)

Few people took notice of the many river changes, but in 1882, according to William D. Cram, writing in a January 1938 Union, the shifting sands left the White Rocks alone at the center of the river and sportsman Frank E. Beckman of Haverhill built a gunning and fishing camp there. The river mouth continued to shift from side to side, making it appear that White Rocks was moving. In the 1890s, the channel became narrower north of the rocks and wider on the south. At low tide, the rocks were joined to the mainland by a spit of sand and the area became known locally as Beckman’s Point. Sand continued to fill in, and finally the channel was navigable only at high tide; then one night, following a major storm, the entire area filled in, forming a new southern end of Hampton Beach.

Since no one apparently had ever occupied White Rocks before, Beckman claimed it as a squatter, and others, mainly from Seabrook, joined him on the newly created “island,” building camps and cottages where they lived in the summer while fishing and clamming in the river. The Town of Hampton, always diligent in protecting its public lands from squatters, soon took action against those on this new land. The Superior Court had previously ruled that the Town did have jurisdiction over all land at the Beach not owned by individuals, and at the 1903 town meeting, the selectmen were instructed by voters to remove all squatters and buildings from White Rocks Island. In late August, the owners of the 10 houses were ordered to remove their buildings by September 1.

It is not clear whether or not this action was carried out for all of the cottage owners, because the Union noted in a September issue that a deal had been made, giving the squatters permission to remain, provided they paid rent. A Union report following the 1904 town meeting, however, says that Beckman’s house was torn down and that on the night before town meeting he had the selectmen arrested and held in $5,000 bond. The case finally went to court, and, in November 1905, a verdict was granted in favor of Beckman. The court ruled Beckman did own the land because he had occupied it since 1882, and, although the Town did trespass on his property, there was no unnecessary damage because his furniture had been removed and stored before the cottage was razed. Beckman rebuilt his house and it became a local landmark for many years.

The Town laid out lots in the area on the following streets, each extending from Ocean Boulevard toward the ocean: Haverhill, Grafton (now Bradford), Atlantic, Boston, Concord, Dover, and Franklin. The latter are now gone and the other streets are now part of the Pines section of the Beach. The first mention of rent being received for White Rocks Island leases is carried in the 1908 town report, when 27 individuals paid $8 per lot. The next year, there were 50 paid leases and in 1910 the total was 70, netting the Town some $560 for which they had no expenses. For a few years, this was the Beach’s largest cluster of summer cottages. By 1914, however, the number of lots was down to 52, with some 18 individuals owing back rent for one to four years.

Between 1914 and 1915, the number of lots at White Rocks Island was reduced from 75 to 25. Once more the fickle river was changing its course and, at the same time, the sea was washing away ocean frontage. In February 1914, the Union reported that the worst ocean storm since 1898 had hit the coast. One White Rocks house washed into the sea and foundations were damaged on two other houses. By June, according to the paper, many houses had been moved back from the water’s edge: “The point of land nearest to the ocean is totally gone and there is a deep channel where land formerly existed. The Beckman cottage, on a group of rocks, is now a total island with a half mile of water between it and the mainland. Other property owners have secured lots elsewhere and moved their cottages there.” Some suggested that the construction of the Mile Bridge may have been the cause of the shifting sands, because the filled-in northern channel began to open again after the bridge was built. By the 1930s, the channel had moved entirely north of White Rocks and Beckman’s Point was attached to the mainland on the south side of the river, the situation that exists today. This shifting of the river led to one of Hampton’s most important court cases in this century, a case discussed elsewhere in this book.

In July 1914, another storm washed away 40 feet of the island, making a total of 400 yards of beach removed since the previous winter’s storms. While Jere Rowe was said to be making plans to move his store, cottage, garage, and barn, at the same time Langford and Dow were announcing the opening on the island of their new 30-room hotel, complete with electric lights. By the spring of 1915, only 42 cottages remained on White Rocks Island. (Apparently some lots contained several cottages, and it is unclear from town reports and newspaper articles just where the line was between the northern end of White Rocks Island and the southern end of the Pines section. Some reports may have mixed the two together, resulting in the discrepancy in the numbers of lots listed.)

A November 1919 storm at White Rocks caused thousands of dollars of damage as 18 cottages were destroyed, the most serious Beach loss since the 1916 fire. Intact houses, complete with furniture, were lifted from their foundations and floated out to sea. (Former Precinct Commissioner Fred Gagne says he “corralled” some floating houses, claimed them, and set them up on Epping Avenue where they remain to the present day.) In February 1926, two cottages were washed away and others were saved only due to a wind shift. The following February, the Atlantic House, which had been undermined by previous storms, finally toppled. By November 1928, about all that remained of the original development at White Rocks Island was Beckman’s house, perched on the ledge. The cottage remained a local landmark and the subject of postcards until it burned in 1935. After 1928, newspaper comments about White Rocks Island were referring mainly to the southern portion of what is now called the Pines section of the Beach.

The highest tide in 14 years hit the beach in April 1929. The storm, accompanied by 60-mile-an-hour winds, hit during the night, and several people had to be rescued by boats. Among those rescued were future Precinct commissioner and Mrs. Fred Gagne and their family of four small children, including future selectman Diana Gagne Lamontagne. When Coast Guardsmen arrived for the rescue in the early morning hours, the water was waist deep in Exeter Street and the Gagne house was in danger of losing its foundation.

While the transient nature of Hampton River and its effect on White Rocks Island is an extreme example of the erosion problems at the Beach, other areas also received heavy storm damage, and the Town continued to appropriate money for breakwaters and to ask for assistance from the State. About this same time, Union publisher Charles Francis Adams and others appointed to a development committee by Governor Huntley Spaulding began to push for a joint marsh- development/erosion-control project. Their plans were announced in July 1928, and in March 1929, just weeks before the April storm, the American Coast and Shore Preservation Society announced that its annual meeting would be held at Hampton Beach in June. George Ashworth, an officer in the national group and a vice chairman of the governor’s development committee, resigned as president of the Chamber of Commerce to devote all of his spare time to the other two projects. The development committee said that between 1911 and 1928, erosion had taken 50 acres of buildable land, including 200 house lots, streets, sewers, water mains, and $50,000 worth of breakwaters.

Some 16 eastern states were represented at the June meeting of the Shore Preservation Society, and they heard James Goldthwait, a Dartmouth College professor and State geologist, suggest that part of the erosion problem could be solved by prohibiting people from hauling away sand by the truckload. Later, the state attorney general authorized Police Chief Harry Munsey to arrest anyone removing sand or rocks from Hampton beaches.

The late winter and spring of 1931 saw repeated storms hit the New Hampshire coast. A January storm caused 30 to 40 White Island houses to be flooded over their first floors. A March storm destroyed 15 cottages and others were saved only because they previously had been moved to the lettered streets. North of Boar’s Head, waves were tearing up the highway and damaging oceanfront cottages. Here some 30 feet of beach was washed away. A March storm destroyed four of Jere Rowe’s cottages and also demolished the Ring popcorn stand, which had been situated on the beach in front of the Casino for nearly 30 years.

Coincidentally in March, Professor Goldthwait released his study of White Rocks Island, which he had conducted for the Federal Coast Erosion Board. He cited four causes for the problems: storm waves, undertow, ‘longshore currents, and tidal currents. When all four forces were working at once, he wrote, the large amounts of unstable sand at the river’s mouth shifted back and forth. The beaches north and south of Boar’s Head were protected somewhat by the Head, Goldthwait explained, but White Rocks Island and the river mouth were open to the direct effects of the storms. Goldthwait said the erosion was not steady and there were no regular cycles of change, but he suggested stabilizing the mouth of the river as a partial cure. He also suggested that because so much of the New Hampshire coastline was privately owned, White Rocks Island would make an ideal state reservation. Despite loss of sand due to natural erosion, Goldthwait and others noted that large amounts of sand still were being hauled off the beach for various construction projects (including the Town’s Centre School). He urged that the practice be stopped.

The 1931 town meeting authorized a committee of five members to ask the Legislature for funds for a new breakwater. Their effort was rewarded when the House and Senate passed a $60,000 appropriation for a new breakwater, with the provision that the State would assume supervision for the land between the highway and the ocean from the Coast Guard station to the north side of Boar’s Head and from the Head south to Haverhill Street. No commercial concessions would be allowed on the sand. The latter point might have seemed unnecessary, but in 1930 Selectmen Elroy Shaw and Warren Hobbs outraged Town and Beach residents when they signed a $125 annual lease with Armas Guyon and Ralph Moulton, giving the latter men the right to build a miniature golf course on the sand opposite I Street. Selectman Harry Munsey said he knew nothing of the lease. At an adjourned town meeting prior to the Legislature’s action, the selectmen had opposed the state takeover, but others, including Ashworth, said it was the only solution to the breakwater problem. No action was taken because at that time the legislation was only pending. In June and August, special town meetings were held to act on the State’s proposal, and both times the voters said no to the plans. Following the negative votes, the Town expended $5,000 (previously appropriated) on a breakwater from Haverhill Street to White Rocks Island. No action was taken on the breakwater issue at the 1932 town meeting because the Town was then under pressure from the State to repair or replace the Beach sewage system.

In late March 1931, federal engineers came to the Beach to tour the problem areas with Governor John Winant and George Ashworth, and plans were announced for a joint state-federal breakwater study. The federal report on White Rocks Island, released in September 1932, called for stabilizing the mouth of the river with jetties to be built north and south of the river, at an estimated cost of $610,000. The report indicated that the mouth of the river had been moving back and forth at least as early as 1776, and that since that time Hampton Beach, in the vicinity of the river, had shifted over a large area, as much as 2,300 feet east-west and 1,700 feet north-south. The report said that since 1912, 251 building lots had been lost, 127 houses washed away or moved away, and the waterline moved back 2,780 feet, despite the construction of two concrete walls and a piling breakwater at a cost to the Town of $100,000.

In January 1933, another major storm hit the New Hampshire coast. At the Beach, water was 3 feet deep on the boulevard, many storefronts were damaged, the playground was washed away, and all of the breakwaters were submerged under the crashing waves. Ring’s popcorn stand was wrecked again, the Town’s concrete breakwater at the police station was undermined, more White Rocks Island cottages were carried out to sea or damaged, and the whole beachfront, including the highway between 14th and 7th streets, was washed away.

Meanwhile, George Ashworth and Hampton Union editor Edward Seavey had been tossing barbs at each other over the state proposal. A Seavey editorial questioned a guest editorial in the Manchester Union written by Ashworth, who “repeatedly separates the interests of the town and beach. There never was, there never can be a divided interest.” Ashworth said, ” … short-sighted factions in the town will not cooperate with the beach … and the fact remains that the future of Hampton Beach depends on taking protective measures to prevent an entire obliteration of three miles of New Hampshire coastline.” Ashworth claimed the vote against giving the State the quitclaim deed to the Beach was a vote against the Beach by the “Town.” Seavey contended the vote was so close it would be hard to assign the votes, and he believed the no vote resulted from “the campaign of threats indulged in by those overzealous champions of the cause ….” Seavey said no one knew where the idea of the quitclaim deed came from: “It is very difficult to overcome suspicion of its unexplained source.”

Ashworth said the State’s request was reasonable, since it could not be certain that the Town would not again lease out beach space for private enterprise, as it had done for the golf course. Seavey said Hampton was entitled to state aid for the breakwater, and it should be given with no strings attached. Hampstead legislator Frank Emerson, a Beach resident, filed a bill that called for the State to take the beachfront by eminent domain. Many townspeople protested any attempt by the State to take the land, but after the January 1933 storm, Seavey editorialized, “In the wake of this great disaster, petty differences must no longer exist and a constructive program must be agreed upon by the state and the town for the reconstruction of the beach front.” In February, the selectmen appeared before the governor and the council, asking for the State to take over the breakwater north of Boar’s Head, with the Town to build the breakwater south of the Head. They requested that the proposal be considered part of the aid to the unemployed. This plan was not accepted by the State.

Finally, Emerson’s eminent-domain bill was rewritten, calling for the State to acquire the Mile Bridge, to build jetties and breakwaters to stabilize the mouth of the river, and to build a breakwater to protect the state highway and the beach between the Coast Guard station and Boar’s Head and from the Head to Haverhill Street. As a condition for construction, Hampton would convey to the State all of the Town land between the highway and the ocean, from the Coast Guard station to Haverhill Street, except Boar’s Head. Once the land was transferred, it would “forever” be kept for park and recreational purposes and no commercial concessions would be permitted, except that the Town would be allowed to maintain buildings for the Chamber of Commerce, the bandstand, and other buildings for public use and convenience. With the approval of the governor and the council, the Town could also build sidewalks. The bill would appropriate $450,000 for the work, and $60,000 appropriated in 1931 was to be added to the total.

The bill initially provided for the North Beach breakwater, the area most threatened; at this point, White Rocks Island, which began as a development about 30 years earlier, had nearly ceased to exist, most of its house lots being again part of Hampton River. Prior to the 1890s, the North Beach section was undeveloped, except in the vicinity of the junction of the boulevard with High Street and Cusack Road. Here the Leavitt family had been operating a boardinghouse and fishermen had their shanties on the beachfront. It is probable that a long dune stretched along the oceanfront from the area of Winnacunnet Road north, and this protected the land behind from most storms. On February 24, 1723, a bad storm had changed this area. The marsh behind was called Huckleberry Flats. The storm flooded the flats and, when the water subsided, a large pond was left into which Nilus Brook flowed. Eel Ditch was dug from Winnacunnet Road (then called the Causeway) to Hampton River to create an outlet. Along the marsh edge of this section was a rough, nearly impassable road known as the King’s Highway. When the new oceanfront road was built from Boar’s Head north in 1892, it is likely that the long dune was leveled, thus removing the protection. After the new road was completed, the Town eventually surveyed the land into lots and many houses were built facing the ocean. These houses were under siege every time a storm crashed along the shore, and it was here that all parties agreed that the first breakwater should be built.

The Town had no choice but to accept the terms of the bill, and at a special town meeting in April 1933, voters approved the draft of the land transfer proposal by a 5-to-1 margin; then the Legislature passed the measure and it became part of chapter 159 of the state laws. A July special town meeting finalized the legislation. In October, the selectmen signed the quitclaim deed conveying the land to the State, and the community’s long battle against the sea was nearing a solution. Work on the 3,900-foot North Beach breakwater, running from the Coast Guard station south to Winnacunnet Road, began in April 1934 under a $219,000 contract awarded to Warren Bros. Construction Company of Boston, and the concave wall was completed by August. Homer Johnson, under a subcontract, used his eight trucks to haul 57 carloads of cement, 20,000 tons of granite block, and 8,000 yards of gravel for the breakwater project.

The construction was held up for a while as state officials pondered the disposition of 10 bathhouses, built many years earlier just south of the Coast Guard station under “squatter’s rights.” Considered unsightly by many residents, the bathhouses were ordered removed by vote of the 1925 town meeting, but residents reversed their decision the following year after a lively debate. The little structures remained in place until 1934, when the land was transferred to the State. In April 1934, at the request of the State, nine of the bathhouses were moved and one was torn down.

While the breakwater project was underway at one end of the beach and the new sewage treatment plant was being built at the uptown edge of the marsh, the new jetties were being placed at the mouth of the river. In August 1934, the contract for jetty work was awarded to Merritt, Chapman, and Scott of New York and Connecticut, the only bidder, for $294,043. It was estimated that 18,600 tons of stone and 8,600 tons of rip-rap would be needed. Sand dredged from the river channel and from a boat basin west of the Mile Bridge was pumped onto the southern tip of Hampton Beach, creating 50 or so new acres of land, which now comprises the area of the state bathhouse and parking lot, then called the state reservation. The north jetty was built first, extending out to Town Rocks, and completed in 1935. Behind the north jetty was placed 600,000 square yards of fill, covering 45 acres 10 feet deep, the largest fill ever in the state, the Union proclaimed in March 1935. It further reported, “The jetty has changed the river currents and eddies and the result appears to be an accretion along the entire length of the main beach at Hampton …. If this process continues, Hampton will be able soon to boast of a beach as wide and as beautiful as that which made it famous in the early nineteen hundreds and the forty-five acres of made land, adjacent to the north jetty, will become one of the finest of the State’s recreational areas. The south jetty will be submerged at high tide and behind it will be pumped 200,000 square yards of fill.” Actually, the south jetty was delayed because the State ran out of money and the 1935 Legislature had to appropriate an additional $80,000 for the work. The total cost of the jetty project was $350,000, which was paid from toll revenues on the Mile Bridge.

The 1935 Legislature authorized $5,000 for the parking lot, and, in 1937, $75,000 was voted by the Legislature to construct the bathhouse that made up the original Hampton Beach State Reservation. Dedicated on July 3, 1937, the new beach facility was not without controversy, as many Beach merchants objected to what they called competition from the State. It was, however, just another of the many disagreements between the Town and the State over the beach and its management by the State. During its first years of operation, the state bathhouse operated at a loss, and the State at various times was forced to cut its work force and to offer free parking, although the charge had only been 25 cents per car. There were elaborate plans for a saltwater swimming pool and sports fields at the reservation, but for nearly 50 years few improvements were made to the facility. Finally, in 1986, as part of a major facelift for many of its coastal facilities, the State tore down the the old bathhouse, leaving no building there for 1987 but opening a new structure in 1988.

By the terms of its takeover of Town land, the State also agreed to build a breakwater south of Boar’s Head, but available funds at the time permitted only a half mile of construction. In April 1940, another disastrous storm hit the Beach, and, as a result, the State announced plans for a $300,000 breakwater from the Ashworth south to Haverhill Street. Although money was authorized by the 1941 Legislature, the growing threat of war called for other priorities and the new seawall was postponed until 1946. The $212,000 seawall construction began in July, and the 3,500-foot barrier with boardwalk was finished in the summer of 1947. With this construction completed, many people figured the beach erosion problem had been solved, but within another decade, millions more dollars would be spent to keep back the sea. It is true that the breakwaters have prevented the type of property damage periodically caused by storms in the early decades of this century, but erosion continues as the sands on this barrier island come and go with the seasons and the storms. At several different times, Hampton River has been dredged, and the sands, thought to have washed off the main beach and into the river, have been placed back on the beach — only to wash back into the river. In the 1930s, some people argued for a jetty built south from Boar’s Head to protect the main beach, and this idea occasionally resurfaces, but the expense and the lack of any evidence that the jetty would work have left the proposal on the shelf.