HAMPTON: A CENTURY OF TOWN AND BEACH, 1888-1988

Chapter 6

Back to previous chapter — Forward to next chapter — Return to Table of Contents

New Hampshire’s short coastline has had its share of shipwrecks. Sailing vessels bound for Portsmouth, Gloucester, or Boston occasionally became lost in fog or were driven ashore by storms. Often ships came ashore on Hampton Beach, although the most famous wreck in town history was the Rivermouth, lost with eight people shortly after leaving the harbor in October 1657.

In 1764, the mast ship St. George came ashore on North Beach. While all hands were saved, most of the cargo was lost. Two cannons and other items presumed to have been on board the St. George were found by skin divers in 1963. It is claimed that the gray rat was introduced to Hampton as a result of an eighteenth-century shipwreck on Boar’s Head. Three schooners came ashore on the Head in the fall of 1869, but all were later refloated, albeit badly damaged. The British steamship Sir Francis was wrecked on this shore in 1873.

Concern for the lives of seamen led to the establishment of the Hampton Beach Life-saving Station in 1898. In February 1896, three coal-carrying, three-masted schooners had been unlucky enough to be just off the coast when caught in a terrific snowstorm. About 3 P.M. on a Sunday afternoon, Hampton Beach residents saw two schooners just offshore. One of the two was the Florida, which was able to get back to deep water but later came ashore on Salisbury Beach and was wrecked, with the loss of seven or eight people. The Plum Island Life-saving Station crew went to Salisbury for a possible rescue of the Florida’s crew. They crossed the rough Merrimack River and walked six miles to the scene of the wreck, while their equipment was being hauled by horses 14 miles from Plum Island up to Newburyport, across the river bridge, and down to the beach. Meanwhile, the Allianza came ashore on Plum Island, losing her captain and two of the seven-member crew. Since the rescue workers were at Salisbury, they were unavailable to assist the Allianza’s survivors.

The second schooner off Hampton Beach was the Glendon, which came ashore south of Boar’s Head about opposite the Sea View. A valiant effort to save those on board was made by Beach residents, volunteers from surrounding towns, and two life-saving crews. The Sea View, which was open year round, became rescue headquarters. A telephone call for help was quickly made to the Exeter telephone exchange, which in turn contacted the Portsmouth exchange, which called the Wallis Sands and Straws Point Life-saving Stations. These crews arrived about two hours later, their powerful team of horses hauling a life-saving boat and other equipment.

At the Exeter telephone exchange when the call came in was Harry V. Lawrence, who was later to write about the wreck and rescue in the April 1911 issue of The Granite Monthly. Lawrence quickly hired a pung (a sleigh) and headed for the Beach. Because snow was blowing off the road, he stopped at the Exeter House and exchanged the pung for the proprietor’s buggy. About three miles from Hampton Beach, he caught up to the life-savers, who were hauling the surfboat on wheels drawn by four horses. At the Beach, Lawrence saw the Glendon offshore, dragging its anchors toward the beach.

The seas were too rough to launch the boat, so the life-savers used their brass cannon to shoot a line out to the vessel, a task made difficult because it was dark and the crew was lashed to the mainmast. A large bonfire was built on the beach, and the firelight revealed the sailors in their oilskins as waves crashed over the decks. One crewman called, “For God’s sake, get us a line. We’re breaking apart.” But the life-savers fired shot after shot before finally catching the vessel. The fire was started again as the ship’s crew hauled out a larger rope, and finally a hawser, for the breeches buoy, which was attached to the mainmast.

The crew of rescuers anchoring the hawser, according to writer Lawrence, was made up of the life-savers, fishermen, sailors, clam diggers, hotel proprietors, town officials, and even young boys. When the surfman pulled the breeches buoy ashore, it held a sailor who called out, “Hello, boys, great night out!” In a short time, all six crewmen and Captain John Mooney were ashore, recovering before a roaring fire in the Sea View Hotel. The sailors had been in the ship’s rigging for three and a half hours before being rescued. An old man at the scene recalled seeing seven wrecks off the beach, and in each case, he said, the crews were saved.

The next day, hundreds of people came to view the wreck, which was relatively intact and could be boarded at low tide. The ship and its remaining cargo were sold at auction a few days later, with John G. Cutler buying the ship’s bell for $87. About 150 tons of the 500 tons of coal was salvaged, but the hull of the Glendon remained on the beach for some years, until storms finally destroyed it.

After this terrible storm, there was considerable agitation for the establishment of life-saving stations for Hampton and Salisbury. In April 1896, the United States Senate quickly passed a bill authorizing funds for a new station to be built between the Merrimack and Hampton rivers. A few months were lost while officials tried to resolve the varied suggestions for the site. A suitable building location on Boar’s Head was rejected when the owner wanted $2,000 for the lot. Finally, through the efforts of Congressman Cyrus Sulloway, a summer regular at Cutler’s the United States Revenue Service acquired from the Town, “for a nominal rent, virtually nothing,” a lot, roughly 290 feet by 265 feet, between the fish houses and bathhouses on North Beach. As approved by the secretary of the treasury, the arrangement called for the government to use the land for life-saving, or a life-boat station, house of refuse, or for a beacon for as long as it wanted, but it would be returned to the Town when no longer needed.

The need for the life-saving station was proved again in late December 1897, when the old brick-carrying schooner Frank was caught in a storm en route from East Boston to the York, Maine brickyard of J. P. Norton. The schooner, off course due to a malfunctioning compass, was near Huckleberry Reef off North Beach when she began to lose her sails. The two crew members struggled to keep the storm-driven vessel off the beach as she was blown around Boar’s Head. In the lee of the northeaster, the sailors placed two anchors and managed to make shore in the vessel’s yawl. The next morning, the Frank came ashore, but she was little damaged. In a few days, her owner sent a work crew and hired a few Hampton men to dig out the sand from under the hull. Anchors were placed offshore, and the Frank’s windlass was used to winch the schooner back to the ocean. She was taken to Portsmouth for repairs.

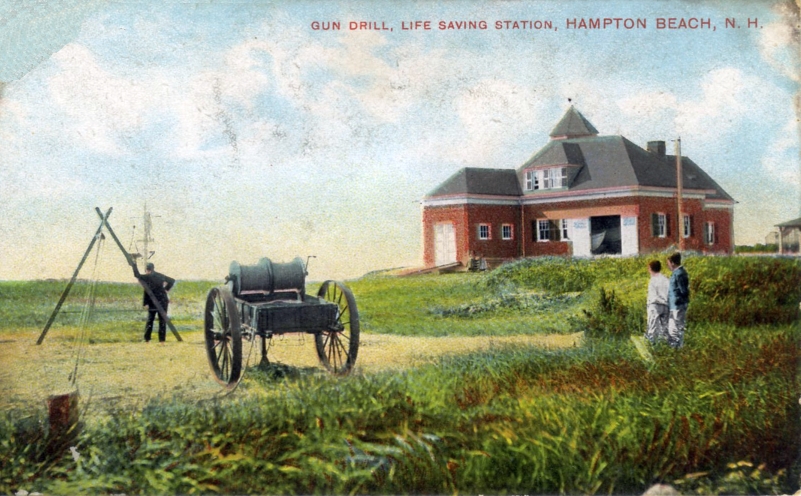

Gun Drill, U.S. Life Saving Station, Hampton Beach, N.H.

Construction of the life-saving station began in July 1898. Most of the building material arrived on the schooner William H. Jewell from Rockland, Maine. The timbers were floated ashore and boats brought in the dry lumber. Contractor W. H. Glover of Rockland was given four months to construct the building, which had two stories and a 30-foot-high tower.

The station was first occupied March 1, 1899, by Captain Benjamin F. Smart, keeper, and surfmen G. W. Palmer, F. N. Garland, and Henry C. Lattime of Hampton; and C. S. Page, I. Burke, T. J. Steward, and Wallace A. Mason. In November, another surfman was added to work until April. No one was on duty in June and July, as the station crew went on leave for the summer at midnight on May 31. The captains remained in the stations year round. Shipwrecks rarely happened in the summer, but if one did occur, volunteers were used for rescue. When the station closed, the men were no longer employees of the United States government, so in August, all crews had to be reexamined (physically and mentally) before being allowed on duty again. During the winter months, they were confined to the station, leaving on liberty days but returning by sundown. Their first duty was to patrol the shore in search of wrecks; they were not beach lifeguards, although they assisted swimmers in distress and were quick to volunteer during Hampton Beach fires or other emergencies. The crew also functioned as an emergency medical team, assisting at accidents and case of sudden illness or injury until regular physicians arrived.

In pleasant weather, a watch was posted in the tower, but on stormy days, two men went on patrol, carrying a time detector that had to be registered at points en route to ensure the integrity of the patrol. They also carried a Caston signal light to use as a warning for ships near shore or to signal ships in distress that they had been sighted and help would be sent. About 1902, a department telephone line connected all stations from Portsmouth to Plum Island. The telephone system included Cutler’s Sea View, which was open all year and commanded a wide ocean view south of Boar’s Head. In 1906, the people of the Beach erected a small building for the crew’s use near the mouth of the river, the southern end of their patrol route.

Sometimes these patrols brought only frustration, as in December 1900 when a violent storm raged off Hampton Beach. Captain Smart was wary of the gale and cautioned his patrols to be extra watchful. Life-saver Edward T. Merrill was patrolling the south beach about 2 A.M. when he noticed wreckage coming ashore. He listened for cries of help but heard nothing, and he looked for signs of a vessel but he could see nothing. Eventually he saw a wrecked dory in the surf, then he came upon the body of Captain Arthur Edldredge. Four vessels had been fishing just offshore and all but one, the Gloucester fishing schooner Mary A. Brown, safely made port. The life-savers could do nothing but wait until morning when the bodies of her four crewmen were found and the hull of the vessel finally came ashore on the beach, where it remained, along with the hull of the Glendon, for a decade, the subject of artists and postcard photographers.

In July 1901, when Station 21 received proposals for 12 tons of coal and one cord of wood for the winter’s fuel supply. Captain Smart still was in charge of the station, with surfmen William Mason, Roderick McDonald, Henry Lattime, Wallace Mullen, and Joseph Blake. Keeper Smart retired in 1916 after 33 years in the Life-Saving Service, which had come under the jurisdiction of the United States Coast Guard when the latter was formed in 1915. Smart was replaced by Captain Jasper B. Myers, who remained in charge of the Hampton station until 1925, when he was transferred to command a ship stationed in Gloucester.

The Life-saving station became one of the most prominent structures at the Beach, and, while its crewmen had a serious responsibility, they had few ship rescues to perform, spending much of their time training and practicing. Most of the men were single, and a number of them married Hampton women and settled in town after their duty was over. As a small child, Alzena Leavitt Elliot, whose parents owned the nearby Willows, often spent time at the station. The men sometimes used her as a “shipwrecked sailor” in their drills with the breeches buoy. For many years, the boat-and-rescue gun drills were popular entertainment for North Beach vacationers.

Eventually, the station received a motorized surfboat, and, as coastal shipping declined, the mission of the Coast Guard locally was directed more toward assistance to the growing commercial-fishing and pleasure-craft fleet at Hampton Harbor. Instead of walking the beach, the two-man motor patrols drove along the coast, stopping at predetermined points, especially at night, to listen for sounds of distress. As Beach traffic and congestion increased, the Coast Guardsmen found it difficult to drive from their station to the harbor where their vessel was moored. In 1938, plans were announced to build a new two-story station near Dover Avenue, and the Town gave the federal government a quitclaim deed to a lot, but World War II postponed construction and it was not built after the war.

In the spring of 1941, the station received a new 26-foot motor surfboat. In May the crew was increased to 17 men, but the following month, as the threat of war increased, Captain Hallie Larrabee announced that nine men had been reassigned to temporary duty elsewhere. In November 1946, the station was closed and decommissioned by the Coast Guard, despite protests from local residents and United States Senator Styles Bridges. The Coast Guard said the closing was justified because of the “poor harbor and lifeboating facilities, its low volume of traffic and its relatively insignificant record of cases involving actually maritime distress in the past ten years.” Following a hearing in Concord attended by some 75 local fishermen, businesspeople, and boat owners, and, with some support from the congressional delegation, the Coast Guard changed its mind. The station was reopened with a six-member crew equipped with only a war-surplus amphibious duck vehicle and the 26-foot surfboat, which had a 20-hp engine.

In 1949, citizens were outraged when the Coast Guard again announced plans to close the station. Testimony at another public hearing in July 1949 revealed that the station had been operating at a total annual cost of $16,000, and in 1948, it had answered 23 distress calls and saved 10 to 12 lives. At this time, the harbor had 102 powerboats, 15 party boats, 12 sailboats, and 196 smaller craft. Nearby Rye Harbor had 40 powerboats, 15 sailboats, and at least 100 smaller craft. While Washington officials considered closing the station, the new Hampton River Bridge was completed, and, with its easily opened draw, river traffic increased. In August 1950, station keeper CBM Charleton Scoville told the [Hampton] Union that five more men were being assigned to Hampton, and the station would soon have a new 36-foot surfboat. This rugged vessel, capable of being capsized and righting itself, was often called upon to go to sea in storms to rescue crews or tow disabled ships to harbors anywhere between Gloucester and Portsmouth. James Tucker recalled one storm in which the local boat guided four dories containing 19 half-frozen men to a safe haven on the lee side of Boar’s Head. They were crewmen on the Ingomar, which had foundered off Plum Island. They had been in the dories for 36 hours until spotted by the Hampton Beach station lookout.

In 1959, the Coast Guard made another attempt to close the station, this time by creating a “manned mooring,” a smaller station at the harbor’s edge close to its two vessels and able to respond more quickly to emergencies. Again the Coast Guard backed down in the wake of heavy local and political opposition. Finally the station was shut down in the mid-1960s, with the Coast Guard operating from a temporary facility at Hampton River from 1967 through 1969.

The 1969 annual town meeting authorized the selectmen to acquire the North Beach property used for the Life-saving Station. The federal government accepted the Town’s bid of $3,000 for the building, the breakwater, and the antenna. Various Town committees pondered what to do with the property, considering such ideas as a youth center, an aquarium, leasing for a church, razing the building to make way for a high-rise condominium or a parking lot, or selling the land for house lots. While some people wanted to dispose of the property for a monetary return to the Town, Hampton voters in 1973 first appropriated $1,000 to raze the building [by a controlled fire by the Hampton Fire Department], which was done on June 1, 1973; in 1974 they voted not to sell or lease the lot; and after the selectmen approved a park plan submitted by Hampton’s American Revolution Bicentennial Celebration Committee, the 1975 town meeting voted to make the site a park, named “Bicentennial Park” in honor of the Nation’s two-hundredth anniversary. The Bicentennial Committee received a federal grant for half the cost of the granite marker in the park area, which proclaims, “Bicentennial Park, Dedicated June 14, 1975, Former Site of the U. S. Coast Guard Station.” Situated next to Ruth G. Stimson Park and the two remaining fish houses, the area is the most attractive noncommercial space along Hampton’s beachfront.