History Matters

By Cheryl Lassiter

Hampton Union, March 18, 2016

[The following article is courtesy of the Hampton Union and Seacoast Online.]

1920 postcard view of the ball field behind the Hampton Beach Casino.

Twenty-first century baseball historians are an unromantic lot. By exposing as myths Abner Doubleday’s invention of baseball and Alexander Cartwright’s “father” status, they’ve altered our view of the game and stripped away some of its mystery.

Lucky the fans of 100 years ago, their joy undisturbed by the modern day historian’s dull realities. By the post-WWI era, baseball and its creation myths had seeped into the national consciousness like a bubblin’ crude, the game solidly fixed as America’s favorite pastime, deserving of the nickname “Old King Baseball.” From the sandlot, the shoulder steak circuit, on up to the bigs, this era saw the number of leagues and teams nearly double. Baseball was played in every hamlet, town, and city across the country, and no matter the regional accent, fans everywhere thrilled to the game’s simple, onomatopoetic language—the dry crack! of a swung bat that sent a little cork-filled orb of awesomeness sailing for the fences.

Baseball had been played as an organized sport in Hampton since at least the 1880s. When the street railway rolled into town in 1897 and spurred the startling transformation of Hampton’s quiet strand into an overcrowded vacation resort, it didn’t take long for the town, as crazy about baseball as any in New England, to field a team in the new Trolley League to compete against teams from Newburyport, Haverhill, Amesbury, South Groveland, and Lawrence. Jim Delancey was the team’s manager, its ace hitter a member of the Godfrey clan, and its pitcher, a man named Gladding, went after batters “like a savage.” Touted out-of-towners like Perley Elliot of Andover and George Woods of Portsmouth had come over to play for Hampton. But something about the league rubbed Delancey the wrong way, and many of the players were reportedly “very sorry” when the team suddenly and inexplicably dropped out. They found other teams to play, Exeter and Newfields among them, and their triumphant 10-2 record in 1899 earned them a fete at Whittier’s Hotel, compliments of John Hobbs, an appreciative fan from North Hampton. Picture postcards of the time memorialize the games played at the beach.

In 1922 another Hampton nine dominated the game, their resolute mugs captured for posterity, not on postcards sold to visitors, but in a team photograph taken that year by Blake Roberts of the Currier Studio in Depot square. They played Saturdays and holidays on the “Casino oval,” the spacious lot behind the Hampton Beach Casino. Summer sunshine and cool salt breezes made it an enviable location, but it had its drawbacks, too. The beach businesses burned their garbage in a depression out in deep left field, so the outfielder, if he expected to check a run, needed a broad jumper’s leap to clear the smoldering refuse pit (not sure what it signals, if anything, but the Hampton Academy ball field had been located near a dump, too). Without bleachers to sit on, spectators crowded the sidelines, the Casino verandas, and the porches of the Hampton Inn across Marsh (Ashworth) Avenue, making admission tickets out of the question. A beach cleanup man nicknamed “Johnny Doodle” passed the hat for donations to support the team, but the fans weren’t as generous as they might have been; the following year the team humbled itself before the Hampton Beach Board of Trade, asking for their financial support.

First row: Leston “Buster” Holmes, Hampton (cf); Roy Klinger, Ipswich (p); Manager Jim Eastman, Hampton;

Jim Martel, Ipswich (c); Bill Bigley, Somerville and Hampton Beach (rf). 2nd row, l-r: Fred (or Jim) Riley, Exeter (ss, utility);

Horace “Hobsy” Hobbs, Hampton (3b); Clyde “Brownie” Brown, Hampton (captain, 2b); Paul Hughes, Greenland (lf);

Ralph Rowell, Exeter (1b); Charlie Kierstead, Hampton (ss, utility).

The players were mostly working men, organized and managed by Jim Eastman, who worked as a starter for the street railway at the beach. Some lived in town, while others hopped the Saturday morning trolley from places like Exeter, Greenland, and Ipswich. Their captain was acrobatic second baseman Clyde “Brownie” Brown, who had played for the Hampton Academy team, as did center fielder Leston Holmes, whose childhood home fronted on the old Academy Green ball field (while this field shared no dirt with a dump, it was a byway for the cows that were driven to and from pastures up Drakeside Road, making it a minefield of cow pies).

Charlie Kierstead, who in future years would run Charlie’s Lunch from an old trolley car near the town center, was the team’s shortstop and utility player. The guy who could produce the “fireworks with the willow” was Bill Bigley, a Boston College student and King of the 1919 Hampton Beach Carnival. Teammate and left fielder Paul Hughes of Greenland once said that Bigley, whose family ran the Olympia Theatre at the beach, could “smack a ball with a vengeance,” and his .478 batting average made him a crowd favorite. The third baseman was Horace Hobbs of Hampton, who once worked as a conductor for the street railway. As an octogenarian “Hobsy” talked up his boyhood days in Hampton in letters to the Hampton Union, sent from his home in Warwick, Rhode Island, where he had served several terms as mayor during the 1960s.

Beginning with a 1-0, thirteen-inning loss to Newmarket, the Hampton Beach nine played a total of fourteen games in 1922, ending the season on September 9—Mardi Gras Day at the close of Carnival Week—with a 2-1 win against East Manchester AA. With a final record of 10 wins and 4 losses, the team didn’t exactly make it to baseball Valhalla, but for a bunch of guys whose only practice as a team was during the pre-game warmups, they “put up”—as newsman, beach booster, and Board of Trade president James Tucker remarked in 1923—“a splendid article of baseball.” As Horace Hobbs put it in one of his letters, “Nuff said.”

Here’s to this year’s boys of summer; may we witness another splendid article or two.

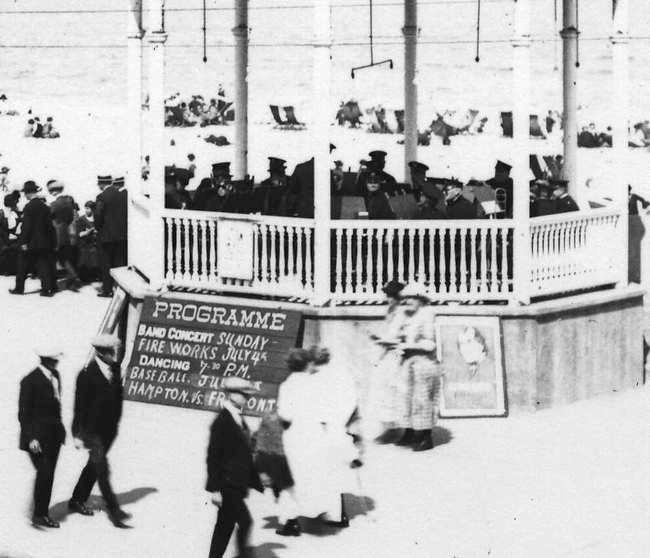

A notice for the July 29, 1922, baseball game between Hampton and Fremont posted on the Hampton Beach bandstand signboard.

History Matters is a monthly column devoted to the history of Hampton and Hampton Beach. Cheryl Lassiter is the author of “The Mark of Goody Cole: a tragic and true tale of witchcraft persecution from the history of early America” (2014). Her website is www.lassitergang.com.