b

The Hampton Beach Precinct, already split by two

major secessions, may not endure much longer.

By Amy Miller

New Hampshire Seacoast Sunday, Sunday, May 22, 1988

(Amy Miller photo)

Call 1-800-GET-A-TAN from outside New Hampshire, and you’ll be told to leave you’re name and number for more information on Hampton Beach. Phone services like this aren’t cheap, and advertising for the scenic, lazy, dazy vacation world of southern New Hampshire’s shoreline is serious business.

The Hampton Beach Precinct pays more than $100,000 a year promoting itself, plus another $80,000 on bands, fireworks, maintenance and recreation. Evidence of the investment’s success is clear on any sunny day in the summer.

The precinct works closely with the Hampton Beach Area Chamber of Commerce, and where the responsibility of one group ends, and the other group takes over, is not always clear. The precinct pays for the GET-A-TAN line, which rings in the chamber office. The precinct pays entertainment costs; the chamber coordinates the events.

There is, however, one big difference between the two organizations. The precinct is paid for by taxes collected from property owners in the beach area. The chamber gets its money from voluntary business memberships and donations.

Many residents of the precinct have been complaining about the system for years. They don’t care if the beach is advertised, but they feel they don’t benefit by its promotion and would rather not have to pay for it out of taxes.

This winter and spring, the precinct lost about 25 percent of its tax base with the secession of two large neighborhoods. Hampton selectmen, who have authority to change the precinct boundaries, agreed to remove property on Boar’s Head and the vast majority of North Beach.

According to some beach residents and business owners, other sections of the beach are likely to follow, eventually weakening and perhaps destroying the precinct system, a desirable or unfortunate result, depending on who you ask.

“The trend is bad,” says Glen French, executive director of the Hampton Beach Area Chamber of Commerce. “The people who live in that area (that seceded) don’t understand what the precinct is accomplishing.”

Firefighter Russell Bridle, whose family has had property on the beach since the turn of the century, agrees the precinct system may be falling apart. “You’re not going to satisfy people in the residential part of the beach now because these other people got out and (they’ll think) why can’t we.”

Bridle and other critics of the precinct believe the 76-year-old district has outlived its usefulness and, as a governmental unit, is performing an inappropriate function. “There is nothing the matter with the precinct per se. It’s time has gone by. It’s just not viable anymore,” says William Gillick, former supervisor of the checklist and a resident of Boar’s Head.

Precinct commissioners, who endorsed the recent secessions, hope the elimination of the largely residential and unsupportive neighborhoods will strengthen the precinct, even though the revenues are bound to go down unless precinct taxes go up.

They see the precinct as essential in keeping Hampton Beach alive and thriving as a family vacation spot.

“Hopefully, (the secessions) will strengthen the precinct and really just involve the main beach, the business part of the beach,” said Precinct Commissioner Terry Sullivan, who owns Farr’s Fried Chicken on the strip.

Everyone agrees that over the past 75 years, the function of the precinct has changed drastically, from a district formed to provide fire protection to one that primarily works to promote the beach as a family resort.

“The concept that this started out for fire protection has turned 180 degrees and it’s all for promotion,” said Gillick, who has lived on the beach since 1969. “It is not serving the people of the precinct the way it’s going now.”

Once a wild frontier

The Precinct, officially known as the Hampton Beach Village District, was formed in 1907 as a subsection of the town of Hampton. Until the turn of the century, the beach had been a true frontier, wild and undeveloped.

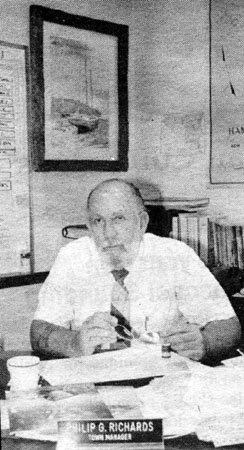

(Amy Miller photo)

“Hampton Beach was nothing but swamp and air,” said Town Manager Phil Richards. “It was like the middle of the Sahara Desert.”

In 1898, the town agreed to lease beach property to the Hampton Beach Improvement Co. for 99 years. The lessors moved in and planted the seeds for one of New England’s busiest beach resorts.

Since the development was private, and far off the beaten track, it was understandable that the town did not want to pay for fire or police protection. Trying to serve the beach with available town resources was out of the question.

“The town couldn’t realistically perform fire services,” Richards said. “The horse and buggy would have taken two hours to get down there, and nobody else was able to reach them and help them in a reasonable amount of time.”

Beach property owners got together at that point and formed the village, a separate governmental unit that quickly developed its own fire station and salt water hydrant system. For a long time, fire protection was the only significant role of the precinct.

Over the years, the function began to change. As the beach became an integral part of the town, growing and expanding to touch the downtown village, the town took increased responsibility for precinct fire protection.

Now, the precinct continues to own its own station and equipment, but all the labor is provided by the town. In fact, Hampton firefighters routinely work part of the year for the precinct and part for the downtown station.

So, while fire service diminished in significance, the precinct became increasingly involved in promotional efforts for the business community.

The village is run by three commissioners, who are almost always business people. At this point, more than 60 percent of the precinct’s budget goes to promoting the beach, with some $20,000 for the fireworks display presented Wednesday nights in summer, another $33,000 for bands, $11,000 for playgrounds and $4,000 for maintenance. About $90,000 goes to fire protection.

Complaints by property owners who do not benefit from the promotions led to a state law redefining the tax methods in the village. Since the 1981 law was passed, residents can apply for a waiver of the advertising, culture and recreation portion of the tax, which this year would be $1.33 out of the $2.08 precinct tax rate. Only property owners who do not own rental properties or businesses can receive the abatement.

The town tax is $30.50 this year. The state Department of Revenue Administration approves of the two budgets and tax rates separately and then combines them to come up with a tax for precinct residents. The town of Hampton handles all collections for the village.

Homeowners in the Boar’s Head area and other neighborhoods that petitioned to get out of the precinct say they should not even have to pay the fire protection portion of the tax. They note that the town responds equally to both the downtown and the beach, and there is no reason they should pay a dollar or two per thousand more than other Hampton residents.

(Amy Miller photo)

“The big argument is that the town of Hampton should take care of fire protection,” said Selectman Glyn Eastman. “They (beach residents) feel they shouldn’t be paying (extra) for protection at all.”

Agreed Commissioner Sullivan, “The real bone of contention is the double taxation on the fire.”

French argues that the taxes might be higher for everyone if the town takes over fire protection.

“They’d probably pay more if the precinct was ever dissolved,” said French, who admits he’s a “ferocious” supporter of the precinct. He suggests precinct taxpayers make back in reduced fire insurance premiums the 70 cents added to their tax rate for fire protection.

Efforts by residents to get out of the precinct are not new. Gillick, a supervisor of the precinct checklist for eight years, has been working with groups hoping to secede since the 70s.

The selectmen agreed back then to remove a large portion of the beach area, including Boar’s Head, North Beach and an area known as the Surfside, which runs from the north side of Winnacunnet Road west of the creek to the town boundary.

Commissioners took the town to court, however, claiming that the drastic change of borders would, in effect, dissolve the precinct, something that can be done only by vote of the precinct.

An out-of-court settlement returned all areas except Surfside back to the precinct. Selectmen agreed that the Surfside area was becoming increasingly populated with year-round residents and was not really a part of the beach community.

Several votes to dissolve the entire precinct have failed through the years. “We got a majority, but we couldn’t get the required plurality,” Gillick said.

This winter, selectmen received the request to remove Boar’s Head, which has property valued at $8 million.

After a well-attended public hearing, and with the blessing of precinct commissioners, the board agreed in February to remove the peninsula just north of the main beach area At the same time, other requests came in to remove from the precinct a strip along North Beach, west to the precinct boundary, and an area between Boar’s Head and the North Beach strip. Those requests were put on hold for discussion.

Earlier this month, selectmen agreed to remove the North Beach area. Since the decision was made after April 1, the beach will still have to pay precinct taxes this year.

The selectmen decided the middle section from Boar’s Head north to Winnacunnet Road and west to the border of the precinct should remain. They also turned down a request from commissioners to keep in the precinct the part of Boar’s Head that abuts Ocean Boulevard, a section that is virtually all commercial.

Residents in the Church Street area have also presented a petition asking to be remokved from the precinct. Selectmen turned down this request as well.

“We felt that area definitely has quite a few rental properties and is practically in the heart of the precinct,” said Eastman, who does not live in the precinct. “If they do ever want to get out they should work within the framework of the precinct.” If voters at a precinct meeting agree to eliminate an area in question, selectmen will automatically go along with it, Eastman said.

LIngering questions

“The question lingers as to what will become of other residents who resent paying the tax. There are rumors that fire protection service could be taken over completely by the town. Sentiment runs rampant among homeowners that businesses should pay for promotion, not taxpayers.

“In every other community we’ve talked to, advertising is not done by the tax dollars, it’s done by businessmen,” said Bridle. “Why should I have to pay because I live at Hampton Beach. My property value is already more because I live at Hampton Beach.”

Bridle has not applied for a tax abatement on the advertising part of the tax because he does not feel he can vote against the precinct and especially the promotional role it plays if he’s not paying a large portion of the tax.

“I maintain the chamber of commerce should do it, period,” said Gillick. “Anyone who wants to advertise, let them join the chamber.”

Gillick noted that even for duplex and small property owners, paying the recreation and culture tax is an imposition. “For me to own a house and have someone say you need to pay $100 so we can shoot fireworks on a Wednesday night just doesn’t go over with me.”

Sullivan argued that anyone who rents out property at the beach benefits from the promotional work of the precinct, not just business owners.

“Anyone who rents anything out and feels they don’t get anything out of advertising is not a very smart business person,” said Sullivan. “We promote Hampton Beach as a family beach and anyone who talks against that is crazy. If we stop the advertising what is to keep Hampton Beach from turning into a Salisbury Beach.”

Agreed French, “If you reduce the advertising, the quality of your customer will go down.”

As far as complaints that most of the commissioners represent the business community, Sullivan notes anyone can seek office, and in any event, 90 percent of the people on the beach are local business people.

French acknowledges that promoting the beach could easily be a chamber function, if the money was there, but he notes tax support for economic development is not all that unusual.

(Amy Miller photo)

“Certainly, the city of Portsmouth invests in its industrial park. Our industrial park is Hampton Beach.”

French works closely with precinct commissioners as well as selectmen, who, in keeping with chamber bylaws, are on its board of directors.

Precinct critics emphasize that they have no personal beefs with the precinct, its management or its managers. “I don’t have any problem with any of the commissioners. They’re very nice people and I can see their point, but it’s unfair,” Bridle said. He suggests the promotional costs would be better paid by a surtax on business owners.

Taxation without benefits

Paul Brochu, a former Hampton police officer, helped organize the petition that got Boar’s Head removed from the precinct. As he wheels a cart of soil through his garden, he points to the kids next door and explains his position.

“It was an unfair tax because we weren’t getting anything out of it,” said Brochu, a member of the Boar’s Head Association who has lived in Hampton Beach six years and on Boar’s Head five years. “This is more of a residential area, as you can see by the kids and everything.”

Brochu suggests the state take care of advertising, since it owns the beach and collects parking fines and meter proceeds.

For businesses, the benefits of the precinct may be hard to ascertain, and for some, the generic advertising may not quite do the trick. As the precinct gets smaller, the cost goes up in an area already expensive for business operators.

“It definitely serves a purpose for Hampton Beach and the entire area,” said Skip Windemiller, who owns a motel, restaurant, small mall and other rental property on the beach. Windemiller pointed out that many landlords who live in town have rental property on Boar’s Head and North Beach, and thus benefit greatly from the crowds drawn to the beach by precinct promotions.

(Amy Miller photo)

Windemiller noted that everyone in the area who owns property benefits indirectly from the advertising and the demand it creates for beach services and property. He acknowledged, though, it might make more sense for advertising to be paid for by a surtax to businesses only.

As far as his own business goes, Windemiller and his wife Debbie own a somewhat subdued, Victorian style hotel on the beach and have found they must advertise independently to reach their target market. “I feel I could live without the precinct,” he said, “We do a lot of our own advertising.”

He acknowledged, though, that he has never had to advertise to fill either his stores or restaurant, both of which inevitably benefit from beach crowds.

As far as Eastman is concerned, whatever the precinct decides is fine by him, a feeling shared by most non-precinct residents.

“I don’t see any problem or big expense if the town did take it (fire protection) over,” he said. “If the precinct wants to be a precinct, we don’t have any problem. But I don’t think the town of Hampton would have any problem if the precinct wanted to vote itself out of existence.”