By Albert N. Dow

Frequent discussion of the subject leads me to think that comparatively few persons, except students of geology, have ever read the description of Great Boar’s Head in Hitchcock’s Geological History of New Hampshire. Here it is in part: —

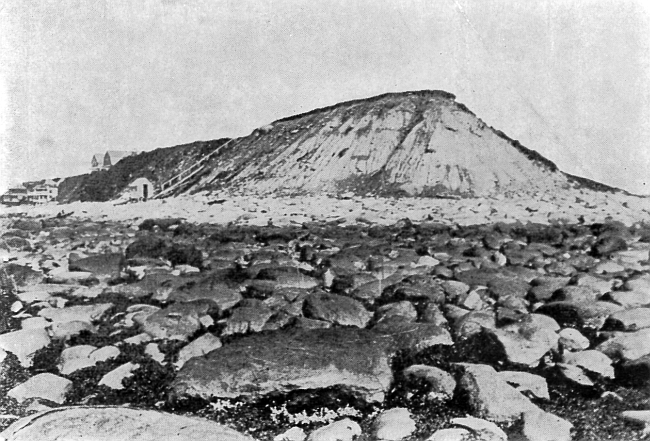

“In the middle of Hampton is a mound of drift about 1300 feet long and 45 feet high. Though small, it may be regarded as a true lenticular moraine. Isolated from all visible connection with any other mass of till by a distance of two miles between the nearest points.

“It has been exposed to the wearing action of the sea from time immemorial and consequently has lost a considerable portion of its mass. The clayey portion of the till has been washed out leaving the stones, consequently the from, size and shape of the mound is clearly indicated at low tide by the remnants. From the extreme point of the cliff, the boulders extend south-east 400 feet. Their northern limit is about a quarter of a mile north of the Boar’s Head hotel.

“Opposite the middle of the cliff the boulders are continuous 120 feet to the fucus (sea-weed) growth (North?), and a single stone projects out of the water as far again. If the hill were restored to its original dimensions, it would probably be 1800 feet in length by 350* feet in width with a course about N. 35 degrees W. (* 350 ft. must be a misprint.) [

“It was the steepest on the south side, Mr. Dumas thinks there has been no wearing away of the hill of any consequence for many years.

“The landing place for boats on the south side has been constructed as it now is for the past 40 years, so that the erosion on that side has been very inconsiderable. The present slight curve in the beach north of the hotel he remembers to have been straight once.

“The upper till is ferruginous comparatively loose in texture, and contains rough stones, rarely any striated, and the material is chiefly the slates found in places two or three miles distant.

“The lower till is composed of very compact gritty earth, slightly clayey, containing numerous smooth and striated boulders, from grains of sand to 15 feet in length. The most abundant rock is sienite. The boulders are all glaciated, but those below high water mark have been smoothed by the water. Of those about 6 feet long were Pawtuckaway sienite, crumpled gneiss of the Manchester and Deerfield range. In pieces about 3 feet to 4 feet long were found; Exeter sienite, the most abundant. No andelusite slate is known to exist within 25 miles. The Manchester gneisses traveled at least 20 miles. I know of no porphyritic gneisses like those occurring here with in 25 miles in a north-east direction, while ledges 60 miles distant agree with them exactly. I found nothing which shows to have come from a greater distance than the trypyramid sienite at 77 miles. The porphyries may have come from a greater or less distance, possibly from the Ossipee mountains.”

This is Prof. Hitchcock’s interesting description of Great Boar’s Head as a geological formation, and no one was then better qualified to give such a description. One cannot doubt the correctness of the deductions concerning the character of the formation or the origin of the material, but there are several statements concerning the original size and shape which are very inaccurate and some statements of conclusions are misleading.

The history says: “the boulders extend north about a quarter of a miles from the Boar’s Head Hotel.” In measuring from the hotel north, it must have been to an apparent line of boulders on shore.

Now there is no definite limit to the boulders on shore north of Boar’s Head. There are apparent limits which change, and which are not apparent “when the sand is out,” as the natives say. This shifting of the sand on the beach, particularly the north beach between high and low water marks, changes entirely the appearance of the beach. Strong easterly winds cause an undertow which carries the sand out. Strong westerly winds bring the sand in. During the summer of 1913, the north cove was filled with sand to the breakwater and very few boulders showed northward. The boulders in the cove at the half tide mark were covered with sand to the depth of 6 feet. Early in the spring of 1914, and again in the winter (1914-’15), there was no sand in sight anywhere between Boar’s Head and the Life Saving Station, a mile and a half north.

It frequently happened that boulders show only as far as a ledge which sticks out of the beach about a quarter of a mile north of the Boar’s Head hotel site, “Cassey Ledge.” It would be interesting to know whether the sand was in or out when these observations were made.

The history further says: “The point probably extended out 500 feet further than at present,” and that “Gunner’s Rock, off the point, is near the end of the rocks.” It is difficult to explain this statement, for the furthest boulder showing in this direction at low tide is about 700 feet from the point, and one may see boulders several hundred feet further still, from a boat in still water.

The fishermen can tell you very accurately where the limit of boulders runs around the Head. Lobsters are caught on rocky bottoms, and in summer the outer line of lobster buoys shows approximately the outline of the outer boulders. By dragging a heavy sledge hammer with a cod-line tied to the end of the handle (a sensitive instrument for the purpose), I found the boulder limit considerably further out on all sides than did Professor Hitchcock, viz.: S. E. 800 feet to his 400 feet, N. E., 1600 feet to his 1000 feet N. and off the point 2000 feet to his 500 feet.

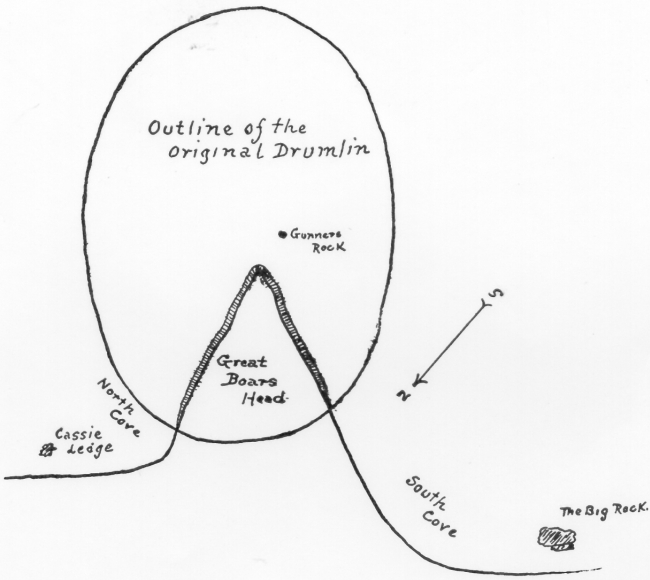

The history says, “the clayey portion of the till has been washed out leaving the stones. The former size and shape of the original mound are clearly indicated at low tide by the remnants.” There seems to be no question of the meaning, that is, that the boulders on shore show the outline of the original drumlin. When the sand is out, the boulders on shore show an unbroken line from “The Big Rock” to the fish houses. The drumlin covered but a small part of this area. The large boulders, only, show approximately the original outline of the drumlin.

A safe premise is that the present north-westerly slope of Boar’s Head is the original slope practically unchanged. This theory is a pretty reliable basis from which to begin to establish the original outline. In Wright’s Ice Age in North America, he quotes Professor Chamberlain, state geologist of Wisconsin, as saying that: “there has been no sensible denudation of deposits since glacial times.” Wright also quotes Croll, who says: “I am surprised at the small amount of erosion which has taken place since the Kames of Scotland were deposited. After thousands of years they retain their sharpness of outline.” There appears to have been no denudation on this north-western slope of Boar’s Head. There is the same depth of loam as on top. The angle of slope is consistent with that of a drumlin and the appearance is not what one would expect in an eroded slope.

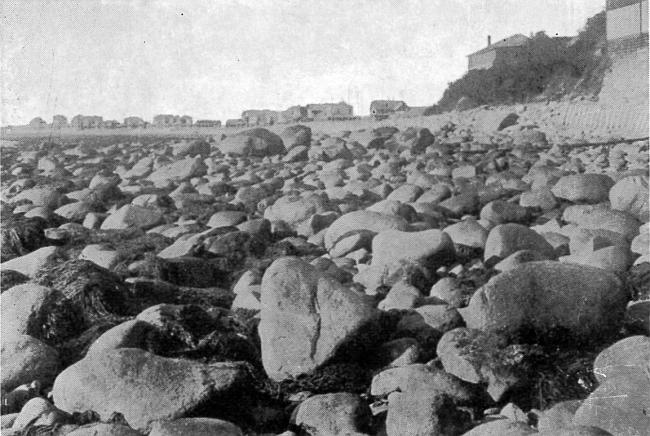

showing difference in sizes of boulders.

If this be the original north-westerly slope, then we might expect to find some trace of the original extension of this slope curving out from either flank, and if we go there with this purpose we find the evidence.

There is a very evident line of large boulders running out by the north cove landing, another, not so well defined, on the opposite side, east of the Leavitt House landing.

The boulders to the south-east of these two lines are all of sizes up to 15 feet long.

This disparity in sizes is what might be expected in a mass of boulders dropped from a drumlin. It is significant also that the boulders inside or north-west of these lines of large boulders are all of comparatively small size, very few exceeding three feet in greatest diameter, the average less than two feet.

The large rock in the middle is not a boulder.

These smaller inside boulders were not dropped here from the drumlin; otherwise there would be large ones among them. None is larger than the sea is able to move. It is natural to think, then, that the force which selected and brought them here was the force of the sea, which would come from the direction of this large supply of boulders dropped from the drumlin to the eastward.

There are no large boulders on either the north or south shore — except one on north beach and a group at “The Big Rock,” and these exceptions I think can be accounted for as not having come from Boar’s Head.

One is directly behind (west of) the highest part of the ledge (“The Big Rock”), another is in a depression on the ledge. Neither of these could have been placed in these positions by the sea. One is on the very edge of the ledge, almost balanced. If this one has rested in this position unmoved by the storms of our time, it never could have been elevated to its resting place by the sea.

The only probable explanation of their presence here is that they were part of the drift deposited here.

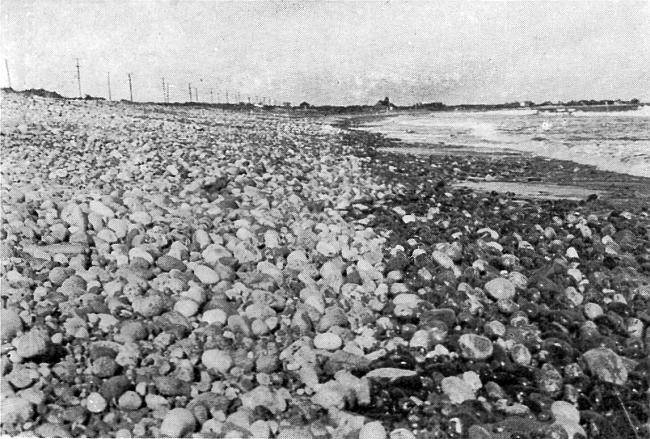

Boulders about half the size

of those in South Cove.

These boulders at “The Big Rock” were not covered like other boulders of the drift by the marsh mud or the beach sand because they were caught on ledges, and they are too large to be removed by the sea. In summer they usually appear to rest on the beach sand, but go there when the sand is out and you will find that every one rests on ledge.

There is only one large boulder on north beach, this also rest on ledge as near as I could ascertain.

With these exceptions, I venture to say that there is not one boulder of large size, inside, or north-west of these lines of large boulders going out from the flanks of Boar’s Head. The inference seems plain and conclusive, viz: — that the rocks on shore do not indicate the size or shape of the original mound, but that this line of large boulders represents approximately the original outline of the north-westerly end of the drumlin; and that the rocks on both beaches were washed in by the sea.

This movement of the smaller boulders includes mainly, if not solely, the smaller boulders above low water mark. It is the opinion of intelligent natives and close observers that there is practically no movement of the boulders below the sea-weed line.

This theory of the movement of the boulders is supported by the fact that the movement is still taking place. Clear away the rocks at any point, as they have done time and again at the Boar’s Head landing, and the storms of one winter, if severe, may be depended on to refill the space from the supply of boulders to the eastward. And this theory is confirmed also by the boulders on the north beach. If they were washed in from where we have located the original drumlin, then the farther they were carried the smaller we might expect to find them. And that is what we do find. The rocks on the north beach are nicely graduated, from the largest in north cove to pebbles at the life saving station.

Professor Wright says: Drumlins are singularly alike in form, materials and direction.

The original Boar’s Head drumlin then, if restored in accordance with this theory, and also by the measurements made, should correspond to the sketch here shown. Elliptical in outline, direction about S. 28 degrees E., 3300 feet long and 2400 feet wide.*

*(Geological history states that the direction of the drumlin was probably about S., 35 degrees E., which corresponds to the general direction of the ice movement in southeastern New Hampshire. But there is more accurate data than this, for there are fairly good scoring on “The Big Rock,” in spite of wave action. These scorings have a direction of S., 28 degrees E., allowing 14 degrees W. for deviation of needle in 1914.)

These were conditions in the early life of the drumlin, the effects of which we cannot closely estimate. Boar’s Head, like all drumlins, was formed under the ice sheet, near the front. Before it was uncovered, there was a subsidence of the land, estimated at 150 feet in southern New Hampshire. In other words, the sea was 150 feet higher. There is difference of opinion as to when the subsidence occurred. Upham think it was just before the recession of the ice front. Winchell believes it was coincident with the dissolution of the glacier. Shaler regarded the depression as due directly to the weight of the ice, and the re-elevation to its removal.

There is evidence of subsidence at the Montreal of 470 feet, diminishing gradually southward. Dana gives the subsidence at New Haven at 20 feet, Nantucket 80 feet, Maine coast 150-300 feet. At Lewiston, Me., the old sea beach is 200 feet above the present sea level and the old beach level at Boston was 100 feet higher than at present.

Upham says: “Southwest of Dover, N.H., there are beds of sand, gravel and clay containing marine shells. A whale’s vertebra, now in the museum at Dartmouth College was found in a newly opened gravel bank in Somersworth in 1843. Several wells in the vicinity of South Berwick, Me., show marine life at a depth of 30 feet, or 100 feet above present sea level. Casts of clams and mussels have been found in a clay bank at Dover Point. Shells have been found 30 feet above high water at Portsmouth and Greenland.” Hitchcock says: “Portions of Seabrook and Salisbury are sandy plains from 25 feet to 30 feet above the sea. They are probably marine beds deposited in considerable depth of water, though not known to contain organic remains.”

Considering this diversity of professional opinion as to the period of subsidence, it would not seem advisable for an amateur to express an opinion on the subject. And yet one who has lived on Boar’s Head and seen the destructive action of the sea cannot conceive that Boar’s Head would not have been leveled before our time if there had been any considerable subsidence of the land after the drumlin was uncovered by the ice. After this submergence there was an emergence of the coast. How long this continued we do not know, but it continued until the New Hampshire coast was at least 20 feet higher than at present.

Then the movement changed and another subsidence began, and this subsidence is now taking place. Upham says a very slow subsidence is now taking place from New Jersey to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Prof. G. H. Cook estimates the present rate of subsidence on the New Jersey coast as two feet in 100 years. Dr. Charles Townsend, the author of “Sand Dunes and Salt Marshes,” gives some interesting facts concerning this subsidence. He says: “In a cove near Bass Point, Nahant, stumps of pines, cedars, hemlock, spruce, ash and maple trees may be seen covered with from 13 feet to 16 feet of water at high tide. There are remains of submerged forests in the harbors at Lynn, Swampscott, Marblehead and Salem and at Kennebunkport, Me.

A recent Boston newspaper said: “Our coastwise skippers have lost many an anchor in the submerged forests off Cape Cod.”

There is evidence of subsidence at Rye (Beach) near the Cable Station. There is a field of cedar stumps visible only at lowest water, and then only when the sand is out. In 1877 more than 75 were counted at the station, the largest being two feet in diameter and three feet high. In 1874 when the cable was laid they were not visible. They are said to extend five feet below lowest water mark.

The Hon. Warren Brown, in his history of Hampton Falls, says that the salt marsh, above the turnpike going from Hampton to Hampton Falls, was an alder swamp since the advent of the white man. The late Charles Lamprey, of Hampton, found stumps in Nilus River deeply imbedded in mud. On the other hand, Professor Cleland doubts much of the evidence offered of recent subsidence in New England, the evidence of the marshes being specially uncertain.

There is local evidence that the amount of recent subsidence might be considerably less than is claimed. There is a cove-beach at Little Boar’s Head, behind which is a barrier of shingle some 20 feet high. Behind this is the marsh which is five feet below mean high water mark. This means that these cedars at Straw’s Point, five feet below lowest water mark, might have grown on land considerably below the mean high water mark, for cedars will grow on land as wet as this marsh.

Still another influence in the wastage of Boar’s Head has been the great storms. Of this there is very little data. No one appears to know very much about how the Head suffered in the great storm of (18)’51 or that of (18)’61. Mr. Eugene Nudd says that in the storm of 1898, a great mass of earth was washed out of the south bank near the stairs. A boat drawn up two thirds of the distance to the top and tied to a juniper was brought down by a wave and smashed. The storm of (18)’51 lasted four days. Water was five feet deep in the road in front of Mr. Lewis Nudd’s house. Mr. Oliver Nudd, Thomas Nudd’s father, boarded up his front door and windows and went ashore for fear of being drowned. The sea came entirely over Plum Island. The (Exeter) NEWS-LETTER of that date says: “The roar of the sea was plainly heard in Exeter, where the water was four feet over the wharves.” Old Mr. Philbrick, of Hampton, who remembers the storm, in speaking of it said: “If we should ever have another like it, I wouldn’t give 15 cents for all the buildings beyond Jenkins’ (Cafe).” I told Captain Perkins, then the oldest inhabitant, what Mr. Philbrick had said and he replied: “I agree with him, I saw the storm of (18)’51, I wouldn’t give 15 cents myself.”

As most of the building within the last thirty years has been “beyond Jenkins’ (Cafe),” which means land on which “The Delta” now stands, the ominous comments of these old inhabitants are not to be laughed at.

The wastage of Boar’s Head has also been modified by the vegetation which undoubtedly covered it at some period. The loam on the Head is from 10 inches to 14 inches deep and black as your boot. Shaler says: “The soil coating of the earth’s surface is, in the main, the product of forest action.”

Dr. Townsend says some of the drumlins of the Massachusetts coast are known to have been forested. When the Mayflower sailed up Massachusetts Bay, Cape Cod was covered with forest growth.

Within the memory of men living, the banks of the Head were mostly covered with red cedars, which strong winds have caused to grow nearly prostrate. Captain Perkins says they were burned, although he could not state the exact date of the event. Those remaining show that they offer considerable protection to the slopes.

Investigation of traditions relating to Boar’s Head shows a surprising discrepancy of statements, particularly about the wearing of the point; concerning this there is a marked disagreement of common opinion with facts. Judge Leavitt, a native, says: “There is a ridge extending off the point two or three miles, showing how far the Head probably extended.” But the government map of soundings shows no ridge here. Mr. Redman, 91 years old, said he could remember when Gunner’s Rock was a gun-shot from the point. This is not very definite. Gunner’s Rock is now 250 feet from the top of the point.

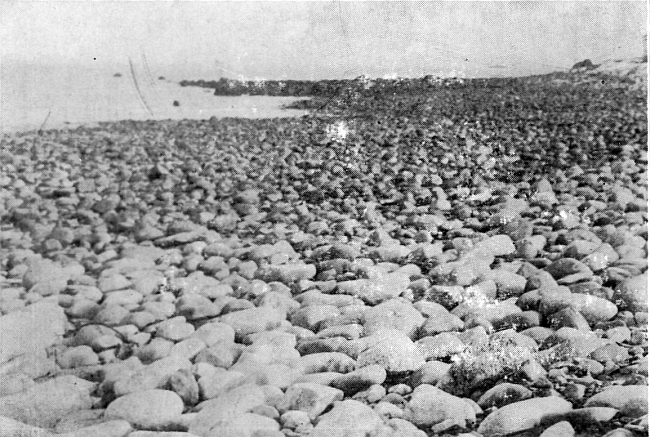

Gunner’s Rock in the middle.

Mr. Philbrick told me in 1910, he then being 89 years old, that when he was a boy, he could throw a cracker from the point to Gunner’s Rock. This statement also is indefinite. Judge Leavitt says that Luth Lamprey told him, that his grandfather Reuben said, that an old man told him, that when he was a young man, Gunner’s Rock was just coming out of the bank. Judge Leavitt estimated this time to be about 175 years ago. Captain Perkins, 91 years old (1912), the oldest man in Hampton, said his grandfather told him that when he enlisted at the beginning of the Revolution, Gunner’s Rock was in the bank and when he got his discharge at the end of the war, the rock had dropped out, say 130 years ago.

Now estimating on a basis of the rate of erosion since 1825, covering which period there is reliable data, Gunner’s Rock came out of the bank between 600 and 700 years ago, say 250 years before Columbus discovered America. This only goes to show the uncertainty of tradition.

the breakwater was built and the slopes sodded.

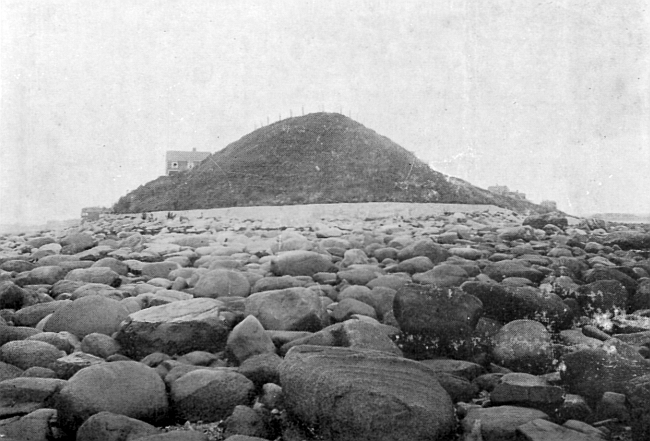

The late Mr. Lewis Nudd said that a certain rock 20 feet from the point came out of the bank about 65 years ago, when he was a boy. Mr. Joseph Dow in his history of Hampton says: “According to surveys made by me, the point receded about one rod from 1826 to 1875.” Mr. Dow’s statement is undoubtedly reliable and it agrees closely with that of Mr. Lewis Nudd regarding the rate of erosion. I recollect the Head as it was in 1875. It was not so steep that one might not walk down without sliding, by careful stepping. Hitchcock says at that time the angle at the point was above 60 degrees. It gradually became steeper until it was almost perpendicular. The upper part began to round off and in 1904 it had an outline as shown in the picture. My opinion is that 10 feet disappeared between 1875 and 1905, at which latter date the breakwater was built. This would make a total of 26 or 27 feet from 1825 to 1905. I believe this rate of erosion at the point is approximately correct.

The north side is receding about twice as fast as the south side. This is due to the fact that the worst storms come from the northeast, that the south side is more sheltered, and also because there is more water in the north slopes (and there appears to be more clay).

Rain falling on a clay bank will not soak in, but runs from top to bottom on the surface. Rain falling on an unfrozen gravel or sand bank soaks in without erosion, unless the bank becomes saturated. The result is faster erosion of clay than sand or gravel.

The greatest destruction to the banks at Boar’s Head is done in the spring when frost is coming out and the ground is full of water. The softened clay, having the consistency of molasses, runs out of the north bank at numerous places, and at times huge wrinkles of clay or sod roll or slide to the bottom in masses of a hundred carloads. The sea is the most destructive factor, but it seldom works. The ordinary flood tide has no effect on the slopes, because it does not reach them. But a great storm which brings high tide and heavy sea removes the talus which has been accumulating for months. The cliff is left in some places perpendicular. The clay, in spots, is laid bare where once there was protecting sod, and in many places, the base is undermined. It thus becomes an easier prey for the elements.

We know pretty nearly where the north bank stood 70 years ago. There is still trace of the stones of an old well on the lower half of this bank.

Judge Leavitt remembered when the top of this well was far enough from the edge of the cliff so that he could walk around it when he was a boy, say 70 years ago. The bank at this point has retreated at least 16 feet in 70 years.

We also have reliable data concerning the location of the south bank 85 years ago. In 1835, Mr. David Nudd built a retaining wall or breakwater some hundred feet long extending nearly to the point. This was destroyed in the storm of 1851. Some of the foundation stones are still in place, showing where the wall stood. These are about eight feet from the present breakwater.

Now, knowing the approximate outline of the original drumlin, and the approximate rate of erosion, we have a possible basis for estimating the time since the drumlin was uncovered by the ice.

If 800 feet have gone from the south side at the rate of one foot in 8 6-8 years, it has required 7000 years. Sixteen hundred feet have gone from the north side. At the rate of one foot in 4 3-8 years, this has taken 7000 years. Two thousand feet have gone from the point; if at the rate of one foot in three years, it has required 6000 years.

In making these estimates of time required for the erosion of Boar’s Head, based on present rates of erosion and known facts, it is evident that the approximate accuracy of the estimate is dependent on the amount which these estimates should be modified by varied conditions.

However varied the conditions at Boar’s Head, here is this inner slope intact. Subsidence of a few feet since the drumlin was uncovered by the ice would have caused the sea to make an indelible mark here.

Estimating that Niagara, at approximately 75 miles from the terminal moraine, was not uncovered by the ice until 10,000 years after the beginning of the retreat of the ice, which is the minimum time estimated by Professor Cleland, then Boar’s Head, at approximately 150 miles from the termional moraine, could not have been uncovered in less than 20,000 years plus; for we cannot leave out of this reckoning, the fact that the ice sheet was much thicker at Boar’s Head than it was at Niagara, consequently the recession was slower.

I do not presume to estimate the comparative value of the data here given for estimating the length of time since Boar’s Head was uncovered by the ice, I only offer this as confirming in some measure, other evidence, and evidence on the length of post-glacial time being so meager any data seems to have value.

My impression was that Professor Hitchcock’s main object at Boar’s Head was to identify the formation and trace the source of its material. His further observations were not based on exact measurements or careful investigation, because he did not consider them of sufficient importance.

Not wishing to have the foregoing statements appear to be in criticism of him, I wrote to him concerning the discrepancy between his statements and the results of my own observations, and in letter dated at Honolulu May 24, 1915, he says: “You must not feel troubled that your conclusions do not agree with those I published. I think I do not hold to my old conclusions. My statement regarding the boulders was not based on actual measurements. I shall probably agree with your conclusions. You must recollect the fact that almost all the conclusions of surface geology have changed.”