HAMPTON: A CENTURY OF TOWN AND BEACH, 1888-1988

Chapter 8 — Part 2

Back to previous section — Forward to next section — Return to Table of Contents

Several court cases in this century have been concerned with land at Hampton Beach. Previously discussed were the Beckman and Newcomb cases at White Rocks Island, the Mitchell case, and the extended proceedings that led to the revision of the Hampton Beach Improvement Company lease. Two other cases are also important — one because it involved one of the most historically significant sites in Hampton, the other because it changed the Town’s boundary.

Fishermen began to use the area at Plaice Cove as a base for their fish operations sometime prior to 1806. A map of Hampton dated that year shows some 16 fish houses located at the site, which was known as “the fish houses.” Nearby was Moses Leavitt’s house of entertainment, which provided food and drink to the fishmongers who came from far inland to purchase cod and other fish from the local men who worked out of this location.

Throughout the nineteenth century, this was an important commercial area. Even today, town maps indicate a pathway off Winnacunnet Road called the “winter road to the fish houses.” The ruggedly constructed buildings, unpainted and weather-beaten, were often passed down from father to son. Although the fishing business at this location declined by the middle of this century, some of the houses continued to be used by fishermen as a place for storing bait and gear. Most of the buildings eventually were converted from fishing purposes to summer houses, owned mostly by residents. As the court case was to show, however, some of the so-called fish houses had never been used for fishing.

A subject not usually discussed in Hampton was who owned the land under the houses. Frank E. Leavitt, who grew up in the area and whose family had lived at North Beach since 1802, said in 1952, “From a young boy, I have been brought up to believe that the fishermen had a right to use the land upon which their houses stood for as long as they were used for fishing purposes and for not longer than that.” In court testimony, Lewis Lester Mace, who had sold one of the fish houses to his son, Harold, said he knew he had owned only the house and not the land, and he had never been taxed since it was customary not to tax the fish houses. The ownership question was tested in 1935 when Edmund Langley, Jr., constructed a building in the area. The selectmen removed the building when Langley apparently ignored notices from the selectmen. The Town’s ownership of the land was legally challenged in 1947, when Alfred Nason of Boxford, Massachusetts, attempted to build a house in the fish-house area. The selectmen were successful in seeking an injunction to halt the construction and the case went to Superior Court in 1948. Nason told the court that in 1921 he purchased the site of the old Abner Mace house and built a cottage there the following year. The Town did not contest his ownership of that lot, but in 1947 Nason began to build another cottage about 55 feet south of his first building. He believed that his three-fourths-acre lot extended far enough south for him to construct another cottage.

In February 1949, Court Master Herbert Grinnell of Derry ruled there were two questions to decide: one was to locate the southern boundary of Nason’s lot, which was ruled to be 10 feet south of his original cottage; the other question was whether or not the Town owned the land south of Nason. Grinnell said that except for the 1898 transaction involving the Life-saving Station lot and its 1933 road and beach transfer to the State, the Town had retained ownership of all of its oceanfront since 1638. The lot on which Nason attempted to build, the master ruled, had once been the site of Mace and Lamprey fish houses, both now gone. The Town did in fact own the land under the fish houses, Grinnell ruled. This judgment was to set of another court case that lasted a decade and that has let bitter memories for many people.

In his decision. Judge Grinnell wrote,

“As time went on, the owners of the fish houses conveyed their property. The methods of conveyance varied. Some owners attempted to convey the land by quitclaim deed and in the settlements of estates the fish houses were variously included in the inventories filed — some as real estate, some as real property ….. In recent years, these fish houses have fallen into disrepair, no longer being extensively used for fishing purposes. A few of the fish houses have been remodelled so that they may be used for summer cottages.”

The latter paragraph apparently made an impression on the selectmen, for in the 1950 town warrant, they included an article “to see what action the town will take relative to the land owned by the Town of Hampton located just north of the Coast Guard Station ….. whether said area shall be divided into lots and leased or handled in some other manner.” On the floor of town meeting, Ruth Pratt amended the selectmen’s article with a motion calling for the removal within six months of all of the buildings except those still used for fishing purposes, and permitting no buildings to be used for living purposes. Edmund Langley, Jr., who owned one of the fish houses, attempted to amend Pratt’s motion to permit the land to be divided and leased, but following an hour’s debate, his motion was rejected 55-132. Then Pratt’s amendment was approved 124-49. Pratt later told Jim Tucker that she got involved at the 1950 town meeting because as a descendant of an original settler, she felt that “certain basic rights residing in this historic town should not in any way be abridged.” The owners of the fish houses must have been shocked. After the meeting, Langley said, “Some day the people will realize that the historic fish houses represent the only link between Hampton’s ancient past, her present, and her future.”

After the town meeting, the selectmen notified the owners of the 13 buildings to remove the structures by September 10. When no action was taken by the owners, the matter was referred to Town Counsel John Perkins, who joined with the Concord law firm of Upton, Sanders & Upton to present the Town’s case. At the 1951 town meeting, voters were asked to rescind the previous year’s action, which would have allowed the fish houses to remain in place. The [Hampton] Union, while urging voters to reject the article, said, “Let the courts decide,” reasoning that the Nason case proved the Town owned the land. It was the last strip of Town-owned property left along the shore and should be kept for the use of all citizens, the paper explained, and only two of the remaining buildings were used for fishing, the rest were summer cottages. The collection of buildings was not attractive, but “rather a shantyville,” according to the Union, and, with proper development, the Town could have a recreation area with a comfort station and a community building with lockers for residents. Having once voted to force the removal of the fish houses, residents reaffirmed their decision by indefinitely postponing the article.

The defendants in the case claiming two buildings were Ruth Palmer and her sons, Philip and Richard; Kenneth and Pauline Langley; and Harold Mace. Claiming one building, individually or jointly, were Shirley MacRae, Winthrop Blake and Chester Marston, Arthur L. Sherburne, Edmund Langley, Jr., Lillian A. Randall, Myron and Alice Norton, and Arthur L. Doggett, Jr. Only Mace and Doggett claimed to use their fish houses as part of their full-time commercial-fishing operations, although one of Mace’s buildings was a fish market.

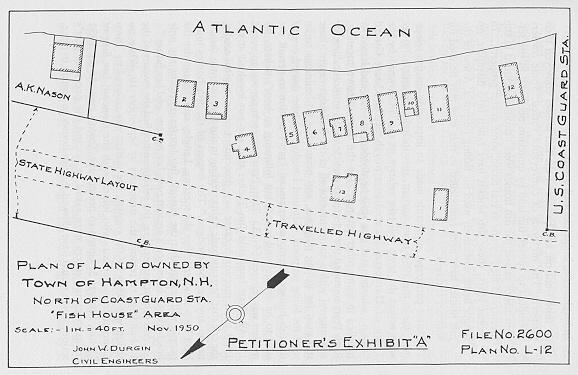

The history of the 13 buildings follows. Each building was numbered by the court as shown on the accompanying chart. The factual information comes from the plaintiffs’ brief, which was filed in the 1959 Supreme Court session. It joins the Mitchell case brief as an important public document because it provides extensive history of Town action in the North Beach area as well as important comment on the uses of the fish houses.

Key to building numbers follows.

1. Claimed by the Palmers, who inherited the structure from Mrs. Palmer’s husband, Charles, who built it in 1904 and used it as a fish market. He had received permission from the selectmen to enlarge the building in 1921 or 1922 and it had been taxed as a fish market since 1916.

2. Claimed by Shirley MacRae. Moved to the fish-house area in 1920 by Ernest White. It was on the site of a Blake fish house and White had sought permission from the oldest Blake, Arthur, to “put a building on his fishing rights.” White fished from the location until 1933 or 1934, then exchanged the building with Stanley J. Knowles for another building in North Hampton. MacRae acquired the building from the Knowles estate in 1946 and she had rented it as a summer cottage.

3. Claimed by Winthrop Blake and Chester Marston. The building was a former horse shed that the two owners and George S. Batchelder and his son, Edward, moved onto the site in 1905. It was used by them as a boathouse for hunting and fishing. George died in 1924 and the Batchelder interest in the house was transferred to Blake and Marston, who used it as a camp in 1948 when they first listed the property in their property inventory forms.

4. Claimed by Arthur L. Sherburne. This building was acquired from Frank E. Leavitt in 1945. The house and lot was one of eight lots, some with buildings, in the area that fisherman Randolph DeLancey left to his wife, Ellen, in 1913. Samuel Hawbolt had built it some years earlier for use as a lobster shack. The Leavitts acquired five of the eight lots from Randolph’s brother, Curtis, and they used this building as an icehouse in connection with their boardinghouse across the street.

5. Claimed by Edmund Langley, Jr. Acquired by Langley from fisherman Charles Blake in 1945. Blake and his father tore down an old Blake fish house (which existed as early as 1877) in 1910 and constructed this building, which was used by Charles until he retired from the sea in 1934.

6. Claimed by Lillian A. Randall, who had acquired it from her late son Bertram. The Randalls bought the fish house for $140 in 1932 from Jacob W. Purington, who apparently got it from his brother, George, who died in 1921.

7. and 8. Claimed by Kenneth and Pauline Langley, who acquired them via a deed from Frank Leavitt. The ages of the buildings were not given.

9. Claimed by Harold Mace, who acquired the building from his father, fisherman Lewis Lester Mace, who had purchased one half of the building from the C. L. Lamprey estate for $13 in 1921 and the other half from Sherburne Hawbolt for $15 in 1927. Harold fished out of Hampton River but used the building to store bait and gear. No taxes had been paid on the building, as the senior Mace said it was not customary to tax fish houses.

10. Claimed by Arthur Doggett. Once the fish house of Alvah Blake, it was acquired by Doggett in 1941 from Everett E. Blake. Doggett used the building in his commercial-fishing business.

(Courtesy Hampton Historical Society)

11. Claimed by the Palmers. This building apparently was acquired by Josiah Palmer in 1861 from Dearborn Shaw. It was passed down through the Palmer family and was used actively by Charles Palmer in his fishing business for about 30 years, until he retired in 1920. Philip Palmer also used the building for lobstering in the 1940s.

12. Claimed by the Nortons. They traced their “ownership” of the land to 1863, when it was transferred from Joseph Palmer to his son, John. An early building was replaced by the existing one after John’s death in 1884. John’s sons, Harry and George, used it for fishing. George sold it to the Nortons for $250 in 1944. No taxes had ever been paid on the property until 1948, when the building as assessed as a camp.

13. Claimed by Harold Mace and used as a fish market. This was the site of the original Eldridge-Moulton house, but the fish market was moved to the location in 1923 by Frank Leavitt and acquired by Lewis Mace in 1938.

The accompanying picture, dating to 1900, was among the exhibits filed with the court. None of the fish houses shown in the old photographs were in the same locations in 1950 because they had been moved back from the shore, about the length of each house, following storms in 1933. Of the nine fish houses shown in the old photographs, only five remained in 1950: numbers 5, 6, 8, 9, and 11. Number 12 was not shown in the old photographs, as it was nearer the Coast Guard lot, but it too had been moved.

The original legal proceedings began in 1952 when the Town filed a bill of equity seeking to quiet title (or confirm its ownership) to the fish-house area. After various delays and pretrial maneuvering by attorneys, the case was finally heard in 1955 and 1956. Judge Dennis E. Sullivan ruled in favor of the Town in September 1957. The defendants — except for Doggett, who was allowed to keep his fish house — appealed. An article in the 1958 town warrant asked the Town to rescind its earlier votes and allow the selectmen to lease the fish-house lots, and to “best protect and presereve their historical beauty …….” The article was not approved, and when the Superior Court rejected the appeal, the defendants next applied to the Supreme Court, which confirmed the ealier verdict in favor of the Town.

[Photo courtesy Nate Piper, Rye, NH]

All of the buildings, including Mace’s fish market, were removed in the late fall of 1959, except for the Mace and Doggett fish houses, which remain to this day [1988]. The Mace fish house was given to the Town and the 1988 town meeting appropriated $2,000 for its restoration.

In 1960, the town meeting voted to preserve “forever” the fish-house area as a public park. In a broadly supported project led by members of the Hampton Garden Club, the fish-house area was turned into a seaside park with natural plantings and a stone post fence. At the 1965 town meeting, the park was renamed in honor of Ruth G. Stimson, the town’s leading conservationist and the person who did “99 percent of the work” of landscaping and planting the seaside park.