HAMPTON: A CENTURY OF TOWN AND BEACH, 1888-1988

Chapter 8 -- Part 3

Back to previous section -- Forward to next chapter -- Return to Table of ContentsOne of the oldest boundary markers in the United States is Bound Rock, marked A.D. 1659. Originally it was the boundary between the towns of Salisbury and Hampton. Later the boundary between the two provinces was moved south, but, in 1768, when Seabrook was set off as a separate town, the boundary between it, Hampton Falls, and Hampton was determined to be Bound Rock, The rock is also marked "H B 1850" to mark Hampton's southern limit in that year. Hampton Falls' land was just a sliver whose apex was the rock. If the boundaries of Hampton Falls, were followed west toward the old Mile Bridge, that town owned an area about 13 telegraph poles wide along the bridge.

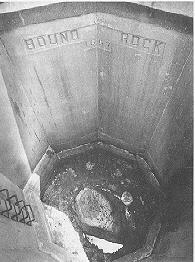

For many years, Bound Rock was located in the middle of the mouth of Hampton River, but as discussed in the section on White Rocks Island, Hampton River often changed its course, leaving the rock on the north or south side at various times. When the river flowed around the barn-sized rock, it was awash at high tide and became a navigation hazard. The rock also disappeared frequently as the shifting river covered it with sand. Its last disappearance was in 1912, when it was lost until the 1930s. Then south of the river, the rock was in an area of sand dunes with no trees around it. The state of New Hampshire placed a concrete wall around the rock in 1937, hoping to protect the boundary marker. Hampton covered this enclosure with a steel grate in 1962.

The controversy over which town owned the land north of the Bound Rock to the river apparently began in 1941, when plans were underway to build a replacement for the wooden Mill Bridge. If the rock was the boundary, then Hampton would own both approaches to the bridge. The town of Seabrook filed a petition in the Legislature seeking to claim by accretion all of the new land, but at the same time taxes on the land apparently were paid to Hampton by Seabrook Beach Community, Inc.

The towns sparred over the question for a number of years, and in 1948 and 1949, the owners of some 31 cottages and 105 lots were taxed by both towns. Finally, in the latter year, lot owner Harold F. MacWilliams sought relief from the double taxation. Hampton filed a petition in Superior Court asking for a determination of the town line. Selectman Harry Munsey told the [Hampton] Union in January 1949 that Bound Rock was the boundary and that Hampton had always collected taxes on the land while it was owned by former governor Francis P. Murphy. After Sun Valley Associates purchased the land from Murphy and began a development, they received tax bills from both towns. Seabrook Selectman Thomas Owen argued, "Rock or no rock, the boundary line as far as we are concerned is the Hampton River. Hampton has no rights over this side."

In July 1951, Court Master Roy M. Pickard ruled in favor of Hampton. He wrote that since a fixed boundary existed -- Bound Rock -- the shifting of the river did not change the town line, as might have been the case if the boundary line had been the river-bank. The ruling was reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in 1953. The wedge-shaped piece of Hampton Falls, was eliminated as the Hampton-Seabrook boundary extended from the rock across the highway to the western edge of Hampton River, then across the river to an island where the three town lines now meet. Seabrook had to refund $5,500 in 1952 taxes that the lot owners had paid to the Town.

For a number of practical reasons, save one, Hampton might have been better off to have allowed Seabrook to claim the land. Heavy summer beach traffic makes it difficult for police and fire equipment to reach the area, and for many years, the section had both water and sewage-disposal problems. The principle involved, and the possibility of collecting more taxes -- especially from (primarily) summer cottages that required few if any year-round services (there were only three full-time residents) -- led Hampton to push its claim. Since the land was primarily sand dunes, it was poor for sewage disposal and residents obtained their water from a few private wells. When Seabrook built a public water system in the mid-1950s, that town stopped its water mains just south of the new town line. When asked by Hampton to extend water to the new residents of Hampton, Seabrook refused, publicly citing no money in the budget for an extension, but privately, probably, still rankled by Hampton's grab of the land that many Seabrook people continued to believe belonged rightfully to Seabrook.

In 1957, when Seabrook rejected Hampton's request for water, Jim Tucker said that the Sun Valley area contained 46 cottages and 105 lots assessed at $600,000 and yielding $12,300 in taxes. Hampton had to spend $3,000 every three years to tar the roads, and rubbish collections and snow removal cost another $300 per year. This provided the Town with a tidy profit, but, as more people began to live year round in the section, the water and sewage problems increased and the residents demanded that Hampton provide them with services. By the mid-1960s, Seabrook and Hampton selectmen had agreed on a plan to have Hampton pay $25,000 for the water extension, then to give the lines to Seabrook. Unfortunately, the 1965 Hampton town meeting rejected the article, so Seabrook voters killed a companion article in that town's warrant. In 1966, Hampton voters finally approved $50,000, which was paid to the Hampton Water Works Company to extend lines under the river to the southside properties. This was the first time Hampton had expended money to bring water to a specific area of town.

The water line broke in 1977 and, for more than a year, this area received its water from Seabrook. A new line was installed in 1978. Sewage also was extended to the area.

Meanwhile, Bound Rock, which Hampton voters bought from a private landowner in 1956 for $2,000, was nominated as a National Historic Site in 1978, the same year in which the Hampton Bicentennial Committee placed a historical marker to indicate the spot off Woodstock Street. The construction of jetties and periodic dredging seem likely to keep the river channel approximately where it is now, leaving Bound Rock high and dry.