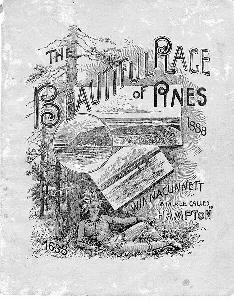

“WINNACUNNETT shalbee called HAMPTON“

[A Sketch of Hampton, N.H., 1638-1888]

By Lucy Ellen Dow, 1888

Lucy Ellen Dow, 1840 – 1896

Two hours out from Boston, towards the far “Down East,” lies the quiet town, whose Indian name, WINNACUNNETT, has been translated as above. A long reach of salt marsh, a shrill whistle at the crossing, an abrupt turn into the village, and speed slackens — the station is reached. But the Hampton of to-day bears little resemblance to the Winnacunnett of two and half centuries ago. Now, rich farms and comfortable dwellings on every hand; then, an unbroken wilderness, trodden only by savages. Along these smooth, broad roads, traversed now by luxurious carriages, lumbering coaches and the humbler farm teams, forest of giant pines once rose, whose interlacing branches stretched far upward in awful majesty, shutting out the sunlight in almost impenetrable gloom. A tangled undergrowth of bushes and vines sprang up in wild luxuriance — pathless all, but for the slender Indian trail, or the accustomed track of the wild beast to his watering-place. The bear and the wolf contested possession with the no less savage red-man; while the gentler deer furnished a target for his unerring arrow, food and clothing for his people, and covering for their rude wigwams. Along the innumerable windings of this modern Meander, the Indian boys fished for plaice (a type of flounder); and by the still pools the young squaw made her toilet. The sea tossed up its waves on the lonely shore, scarcely enlivened, though groups of savages lay basking in the sun upon the sands, or launched their frail canoes and shot out fearlessly over the billows, or shouted to brother savages, returning with their fare of fish. The sharp whistle of the marsh birds, meeting and mingling with the cry of the loon and other denizens of the waves, made desolation doubly desolate.

And yet –, “The Beautiful Place of Pines” was no misnomer. Indian names are rarely, if ever, inappropriate. Broad, open fields, kissed by the summer sun, green with waving corn, and animate with working women, spread out here and there; smaller openings, bright with moss and ferns and wild flowers, broke the gloom of the dark forest, and encircled groves of pine and other growths, giving shade which was not gloom. In such a spot, the Indian brave would stretch himself upon the mossy earth and smoke his pipe and listen dreamily to the solemn soughing of the wind and speak no word for hours; and here the twin flower and anemone grew as delicately fair, the arbutus as sweet, as if the world knew and admired; the patridge-vine and the bunchberries blossomed and fruited, blushed scarlet and decayed, though only the birds knew the story of their life.

In selecting a site for a village, the Indian, stolid, indifferent, hard, though he might be upon occasion, had an eye to beauty as well as convenience; — and one spot, notably, still remembered as “WIGWAM ROW,” invites attention. If we may draw somewhat upon the imagination, taking probability for fact, we have the picture of a sunny hillside, sloping sharply toward the south, the northern crest heavily wooded, and so protected from the chilling winds, and a long line of wigwams looking southward over the meadows below, kept green by perennial springs. Narrow foot-paths radiated from these springs to the several huts, striping the hillside in alternate green and brown. Standing outside his hut, the keen eye of the warrior, looking over the tops of the trees which skirted the valley, discerned, perhaps, some signal from another camp on a height six, eight or ten miles away, and with answering signal told where the war-path lay, or warned of a common danger.

Suggestions of love as well as war, still lurk in many a shady nook near “Wigwam Row” — of young braves, gay in paint and feathers, and dark-skinned maidens, coy and fond.

All these are summer scenes; but winter likewise had its charms; and doubtless, the Indian soul was susceptible to the white radiance of the snow-clad fields, the stillness of the mysterious forest, the clangor of the tumultuous sea. Winter sports, and winter dangers also, dearer still to the warrior, were not wanting. Clad in skins, with snow-shoes on his feet, his quiver at his back, his bow in hand, and proudly conscious of his noble bearing, he stalked forth for the adventures of the hunt. Sometimes, the war-whoop echoed through the wilds, as, joining others of this tribe, he entered on the path of hatred and cunning and treachery.

Whatever their surroundings and pursuits, the men, active only in self-gratification or revenge; the women, hard-working, sad-faced, sharp-tongued; the children, lawless and mischievous, lived their lives and died and were forgotten.

Such, then, was WINNACUNNETT, and such its people, when in 1638, the first white settlers came. Then began such a scene of activity as these wilds had never known; and the Indian, with half shut eyes looked on in covert wonder. Could he have foreseen what all this stir of preparation meant for him, how different would have been his reception of the intruder! Not knowing, amicable relations seem to have existed between the two races for years, with only occasional outbreaks, except in the general Indian wars. Then, indeed, consternation prevailed, and block-houses and garrisons were in requisition. Then it was that the name of Bomaseen became a terror throughout eastern New England — Bomaseen, one of the sachems who signed the treaty of Pemaquid in 1693, only to break it in renewed, and, if possible, greater atrocities; — Bomaseen, whose ugly visage, hideous in war-paint, appeared for a moment at Goodman Lane’s window one dark night, but vanished as that stout-hearted yeoman seized his gun to rush out and defend his home. Lane stumbled, in his haste, and in the momentary delay, the savage slunk away in the darkness, and afterwards boasted: “If you not stumble over kettle, I kill you that night.”

Finger-marks of these fearful times remain here and there, to this day. Here, for example, is an old diary, with the entry, “in the careless upon you to destroy you if ye had not had help from ye Garrison to drive —-” and the sentence is left unfinished. The writer of the diary lived nearly opposite a garrison house, around which a conflict had possibly recently occurred. Hostilities increased as years went by, but for a time, the plantation at Winncunnet was allowed to build itself up in peace.

Rev. Stephen Bachiler, then seventy years of age, as at the head of this new settlement and pastor of the church, already organized. In the quaint language of the day, he wrote to Gov. Winthrop: “We intend to go by a shallop (from Newbury), so that as we hope and desire to have your helpe and our christian friends’s Mr. Bradstreet; so we pray you both to be ready to accompany us * * * * * we were there & viewed it cursorly & we found a reasonable meet place, which we shall shew you; but we concluded nothing.” At this distance of time, and with the present topographer of the town, the location chosen for their permanent settlement seems hardly a “reasonable meeting place.”

A low, wet basin, gradually rising to higher land throughout its circumference, a dense fog hanging over it at night and in humid weather; too wet for tillage, or for crossing easily from side to side — one would suppose that many a spot could have been chosen more desirable in every way than this. It may be that when Mr. Bachiler and his companions came to view the land, this meadow, still kept green by the autumn rains, attracted them. It may be, that the forest was less dense around it than farther back, and so more easily cleared for cultivation. Or, some other cause, not now apparent, may have led to their choice. On the southern border of this basin they built their log meeting-house, and the whole meadow, many acres in extent, was called the “meeting-house green.”

In the course of years, a road ten rods wide was laid out around it and substantial houses, with the heavy oak timbers of that olden time, were built, and became the homes of families, many of whose descendants still occupy the ancestral sites. The meadow, in later times, came to be designated as “Ring Swamp,” by which name it is still known, though much of the land is now tile-drained and cultivated. This royal ten-rod thoroughfare continued for almost ninety years, when the north side was reduced to between five and six rods, and that still generous width remains today, though other portions of the road have been greatly curtailed.

WINNACUNNET, the “Beautiful Place of Pines,” did not long retain its Indian name; for, at the request of Mr. Bachiler, it was changed — the brief record of the act being in the words: “WINNACUNNET SHALBEE CALLED HAMPTON.” (In honor of Southampton, England.)

This Rev. Stephen Bachiler is the “Father Bachiler” immortalized by (John Greenleaf) Whittier in “The Wreck of Rivermouth.” The practical iconoclasts of the present day, however, tear down the beautiful old-time romances with merciless hand; and with “facts, sir, facts,” refute the existence of William Tell, and rob the story of Pocahontas of half its charms. So now, truth compels us to say that the touchingly-told legend of rivermouth rocks is but a poetic fancy, Goody Cole being, at the time indicated, confined in Boston jail, and Father Bachiler having before this, returned to England. The one fact in the case, is the loss of the boat with its human freight, not, indeed, returning from a pleasure trip to the Isles of Shoals, but bound for Boston.

That Goody Cole was regarded as a witch, is certain. That to her sorceries was laid the drowning of two young men, who had incurred her wrath, there can be no doubt. But her home, when she had a permanent home, was far removed from the river, being on this very road around the “meeting-house green.” Goody Cole, at least in her old age, was undoubtedly, in the Yankee sense of the words, ugly. The separation from her husband was inevitable. Scarcely less so, in that age of superstition, was her imprisonment for witchcraft. And when, after spending several years in jail, she returned, and came upon the town for support, it may well have been a vexed question, what to do with her. It was finally ordered that the several families of the town board her, by turns, a week at a time. And so she spent her last days carrying discomfort, and, no doubt, terror, into all those homes. A horrible tradition exists that when she died, her body was thrown into a ditch and a stake driven through it.

In striking contrast to this unhappy termagant, were the twin sisters, Bridget and Jane Moulton, her contemporaries. Their lives flowed peacefully on in such perfect harmony as to attract constant notice; and no less a personage than Rev. Cotton Mather, nearly twenty years after their death, found it worth while to write of them on this wise, for a gentleman in London: “The perpetual Harmony and Sympathy between the sisters was the observation of all the neighborhood. They were never contented except they were together. If the one were desirous to go abroad, the other would be impatient of staying at home. If the one were merry, the other would be airy. If the one were troubled, the other would be chargrin(ed). * * * They lived a Virgin life, and in this good accord, reached about threescore years. Then Death, after a short sickness arrested the one of them. The other grew full of pain, and bid her friends not be in a hurry about her sister’s funeral, for her’s must accompany it. By dying a few hours after her sister, she answered their expectations.”

A brother of these twins was the great-grandfather of General Jonathan Moulton, whose career, a century later, was subject of much criticism during his life, and of distorted tradition every since. He, too, has come down to us in verse; and the poem of “The New Wife and the Old” reveals the weird fancies that have been woven about his memory, — fancies which even ascribe an “early grave” to the wife, who, at her death, had been married twenty-six years and was the mother of eleven children; and which call the middle-aged second wife a “blooming girl.”

This hero’s exploit, most ardently treasured by legend-mongers, is his stratagem to cheat the devil. The story goes, that the General made a bargain with his satanic majesty, to sell his soul for a boot-full of gold, to be poured down the chimney of his house. The devil endeavored to fulfil his part of the contract, but, to his surprise, the gold constantly settled, and the boot could not be filled. Investigation showed that the crafty General had cut off the toe, and so had become immensely rich without losing his soul. Doubtless his wealth was over-estimated. The truth is, General Moulton was in advance of the age in which he lived. Enterprising, shrewd, far-sighted, possibly unscrupulous, — though of that there is no proof, — his schemes prospered, till it seemed that, as with Midas of old, his touch converted everything into gold. One of his transactions was especially odious to the people:

In 1764 (November 30th), a mast ship (the St. GEORGE), always an object of aversion to every liberty-loving colonist, was wrecked on Hampton beach (at Plaice Cove). The disaster was immediately reported to the Court of Admiralty at Portsmouth, and General (then Colonel) Moulton and Colonel Toppan, another wealthy resident, were appointed keepers. Naturally, they lost no time in securing the goods, even before the news of their appointment had reached the ears of the people. Numbers flocked to see the wreck; some coveted the spoils, and raved like madmen when the two Colonels, who were themselves carrying everything away with all possible speed, forbade them. These two men took no pains to explain and conciliate; and when, a month later, they purchased the goods and exposed them for sale, the wrath of the people broke out afresh. A riot ensured of so serious a nature as to necessitate the calling out of the militia.

The term “mast ship,” familiar and hateful in those days, may now be an enigma except to the antiquary. For many years the sovereigns of England claimed exclusive right to all the pine trees in New Hampshire, best suited for masts of vessels. Officers of the government went through the province from time to time, branding the best trees with the “broad arrow,” as it was called,; and any persons felling such trees even on their own lands (outside the townships), were subjected to heavy penalties. Large ships, bringing merchandise to our shores, carried back to England cargoes of these trees, and were hence called “mast ships.”

About three years after the wreck of the St. George, as recorded above, General Moulton lost his house and two stores by fire; and he subsequently built a mansion, which remains to this day, and is cherished as “the haunted house.” It was here, probably, that the ghost of the “old wife” appeared to her successor and robbed her of her jewels; and here, doubtless, the baffled devil contended for his lost vantage ground. Whether he finally obtained the General’s body, because cheated of his soul, deponent saith not; but it is currently reported that the bearers at the funeral declared the coffin to be weighted heavily enough to have been filled with stones. And the place of his burial, “no man knoweth unto this day.”

These ghostly visitors departed long ago, and flesh and blood occupy the mansion undisturbed. It stands in a conspicuous position, a two-story, hip-roofed house, fronting on three roads, and is still outwardly substantial, and little less than imposing in appearance, though innocent of paint and tasteful care. Of the internal adornments, once lavish and costly, no vestige remains, unless, by implication, in the great stairway and the panelled wainscoting.

At no great distance from General Moulton’s house, stands one of much earlier date, the house inherited by Colonel Christopher Toppan, his associate in the mast ship affair. Here, indeed, you have a hint of colonial grandeur. The house and grounds, having never been alienated from the Toppan family, nor having lost the prestige of wealth and culture, preserve the old flavor of aristocracy, though in a modified form. It breathes in the grand old elms; resounds in the brass knocker on the door; speaks in the very footpaths; reposes in the grass-plots and shrubbery. The buildings themselves remain intact, unscathed by the craze for remodelling, even the old-fashioned colors, yellow with red doors, being retained, and reproduced as occasion requires.

This was at one time a garrison house, enclosed by a fence too close and high to be scaled, too strong to be battered down by the Indian foe. Every night the citizens were admitted within the gate, bearing straw couches, which they spread in the yard; the great key was turned; the sentry mounted guard; and thus protected, the people slept in peace. No wonder that the summer tourist now walks back and forth in front of this fine old place, casting curious glances about, with ineffable longings to see the interior. At rare intervals, the house is “on reception,” but always personal friends are welcomed and shown over it with a courtesy which wins for the gentle mistress the warmest praise.

The low rooms, with the summer extending across the ceiling; the deep, cushioned window-seats; the heavy sashes and small, thick panes; the cornices and moldings; the balusters of the front stairway, finished in three separate designs; the narrow, winding side-stairs; all speak of a bygone age. Oh, the tales of two hundred years that the old north parlor might tell! — tales of serenity in the peaceful colonial days, of trepidation in times of war — tales of grave councils and of stately receptions — tales of wedding festivities and of Thanksgiving re-unions — tales of bereavement and heartaches too, since these come alike to the rich and great, and to the poorest cottager. Across a corner of this north parlor is the ancient beaufet, well stocked with rare old china, among which repose a punch-bowl and plate that came ashore in the very mast ship already mentioned (the St. George).

An old lady, dimly remembered by the present generation, was asked what they drank from the tiny cups in Revolutionary days, when tea was tabooed. “Oh,” she said, “they made gruel, and boiled a few raisins in it to give it a pleasant flavor, and that was what they drank from the tiny tea-cups.” On the wall of this parlor hangs a small picture, wrought in a kind of tapestry embroidery by one of the grandmothers of the family, well on towards a hundred and fifty years ago. Made up of “the most grotesque compositions and fantastic combinations” of impossible animals and marvellous earth and sky, it would delight the heart of any lover of the antique; but as a family relic, it is of priceless value. A fire screen of similar workmanship, but of later date, stands in the upper hall.

After the house had grown old, it became a question with the ancestor in possession, whether to take it down and build anew, or repair it. Blessed be his memory, that he decided for repairs!

Some anecdotes worth remembering are told of Col. Toppan. Once, in a gunning expedition on the salt marsh, he accidentally set fire to some hay belonging to a neighbor, familiarly called “Laboring John,” which consumed two stacks. On his return, passing “Laboring John’s” house, he called to him, and remarked carelessly, “I see you have two stacks of hay down by the beach — what will you sell them for?” The man named his price, considerably lower than if he had known that he had the Colonel at a disadvantage; and that gentleman replied cheerfully, “Come to my counting room, and the money shall be ready for you.”

The Colonel was especially fond of pigeon shooting. A pigeon stand consisted of a pole resting horizontally on two crotched stakes, two or three tame pigeons for hoverers and flier, and a net-house — a little hut of evergreen boughs within which the gunner sat concealed. The hoverers were blinded and placed on frames, to be seesawed from behind the screen; a long line was tied around the leg of the flier; the man crept into the net-house, cocked his gun and waited. When a flock was seen approaching, the flier was deftly tossed into the air to the length of its line, where it swayed and fluttered, then gently settled back, and the strange birds came and alighted on the pole to make acquaintance. Now was the supreme moment for the sportsman, who deemed himself unlucky if less than half-a-dozen fell victims to his shot. Col. Toppan’s negro servant, Neb Miller, dearly loved a practical joke; and, one morning, being sent ahead with the decoys, the temptation was too strong to be resisted, to take out the charge from the gun, replace a single shot, ram back the wad, and set the gun in its accustomed place. A little later, the unsuspecting Colonel, seeing an especially fine opportunity to display his skill, fired; but when only one pigeon fell, his chagrin was almost too great to bear.

This Neb Miller had once too long-continued a diet of porridge to suit his taste; and so, to end it, he contrived to open a hole down from the chamber above, over the kitchen fireplace, and to have a line with a slip-noose ready for action; then, watching his chance, he slipped the noose around the short leg of the kettle, tipped it over and drew up the line. When Neb was called down to breakfast, the cook was in great consternation about a kettle of porridge, spread over the floor; and for that morning at least, there was no porridge for breakfast.

All the treasured-up stories of all the old houses would fill a volume. We turn again to tangible, material objects. On the great road to the beach stands an elm tree of gigantic size (at ELMWOOD CORNER); until the storm which will pass into history as the disastrous ice storm of the winter of 1885-86, without exception the grandest, most majestic and beautiful elm the beholder ever saw. The patriarch of to-day remembers hearing his mother say that it was set out the day one of PARSON THAYER’S sons was born, but which son he cannot tell. It matters little, for the births of all PARSON THAYER’S children lie between the years 1767 and 1783, so that, in any case, the tree is more than a centenarian. Under its grateful shade, of over one hundred feet in diameter, the summer boarder swings his hammock and brings the rustic seat. Little children tumble over each other on the grassy sward, bright youth sings love songs, and placid old age dozes quietly. Sadly shorn of its symmetry by the icy grasp in which for days it was held by that merciless storm, one can but hope that kindly Nature will in time repair, with new and vigorous growth, the damage wrought by crashing boughs.

HAMPTON BEACH has attained some celebrity as a watering place. It is not NEWPORT or LONG BRANCH — it has not the aristocratic tone of its neighbor, RYE. It is sui generis in its blending of fashion and rusticity, of bustle and solitude. About the hotels, it is instinct with the polish and parade of elegant society and gay with “hops” and music; and at scarecely a stone’s throw, it is common-place, in the unconventional home life of the cottages. Along the driveways and promenades, it is joyous life, in the stir of pulses quickened by the exhilarating sea breezes; while far down towards the river, on the one hand, and midway between the two BOAR’S HEADS on the other, it is absolute stillness, save for the eternal moaning of the sea — restless, grand, solemn, inscrutable.

GREAT BOAR’S HEAD, or, more commonly, BOAR’S HEAD simply, is a remarkable promontory, midway between the northeast boundary of the town and the river, which forms the southern boundary. The name was given in early times, from a fancied resemblance to the animal; its snout, known as the Point, running far out among the breakers and sixty feet or more above them.

The land gradually slopes back to the general level, but the whole promontory covers several acres, the top of which is a smooth, grassy lawn, commanding one of the finest sea views on our coast. An ample driveway leads up from the main road to BOAR’S HEAD HOTEL, which crowns its summit. This is the veteran hotel of HAMPTON BEACH, built by DAVID NUDD and others in 1826. Mr. NUDD was the GENERAL MOULTON of the first half of the present century, a man in advance of his age for enterprise and business sagacity. His keen eye foresaw the throngs of summer tourists, sweeping down like birds of passage, and he organized a company to build this hotel for their reception. Even his perspective, however, was at fault, and after he became sole proprietor he found it necessary not only to enlarge his house, but to build another, THE GRANITE HOUSE, at the foot of the bluff.

For the last twenty years and more, COL. S. H. DUMAS, proprietor and landlord, has sumptuously entertained thousands who doubtless passed in review before the prophetic vision of DAVID NUDD, long since gathered to his fathers.

Along the southern verge of the cliff, a foot-path, flanked at convenient intervals by rustic seats, descends to another large and popular house, the HAMPTON BEACH HOTEL, on the thoroughfare leading down to the lower beach. On this side, the headland forms, with the general trend of the coast, a sheltered bay, but too rocky to be easily available for boating. Decoy ducks, lobster nets and various fishing paraphernalia, with here and there a channel cleared through the rocks, attest, however, that eagerness for sport or business have in a great measure overcome difficulties. Just within this bay, the larger boats dance merrily at their moorings till peopled from the little swiftly-gliding skiffs, when they spread sail and fly away, perchance to the fishing grounds, perchance to the ISLES OF SHOALS, ten miles beyond, or, it may be, for an idle hour no whither. Occasioinally, a steamer from HAVERHILL or NEWBURYPORT for the (ISLES OF) SHOALS, halts within signalling distance of the Point; and in the season, a mackerel fleet not infrequently comes up over the horizon, numbering two or three hundred sail, gleaming white against the sky.

Such an appearance is unwelcome to the resident fishermen, whose trawls, baited and set with much painstaking on the fishing grounds, are often robbed, leaving empty hooks, if indeed the trawls themselves are not stolen or cut. No redress has yet been found for these robberies on the high seas, for they are committed without the jurisdiction of the courts, or else impossible to prove against individual offenders. Much property in fish and tackle is thus lost every year.

What caused the earth just here at BOAR’S HEAD to swell upward and outward in this fashion is a mystery. It divides the shore into two distinct portions — the LOWER BEACH on the one side, along which is the chief settlement, and the NORTH BEACH on the other. The former boasts of an exceptionally fine esplanade on the sands, broad, firm and smooth, and stretching far down towards the river; covered indeed, at high water, but emerging, solid and tempting at each ebb tide. For dreamy luxury, one has but to lie prone on the slope of any of the sand-dunes in the rear, with umbrella spread for protection from sun and wind, and look down and out upon the dancing, flashing waves, sweeping shoreward in long lines, rolling, swelling, breaking and reforming in endless succession, the same, yet never the same, till the roar tones into a gentle murmur, and sky and wave and shore melt together in the misty vision under closed eyelids.

The NORTH BEACH is essentially different in character from that already described, but no less inviting. Coming from the south side, it will amply repay one who has strength of muscle and some degree of agility, to make the circuit of The Point by stepping from rock to rock at its base. A better idea of the precipitous height can thus be obtained, than by standing on the top and looking down. At low water, this feat can generally be accomplished. Then, if one tires of the rocks, there are places where the cliff can be scaled, though it is by no means an easy climb. But The Point may be avoided altogether by keeping to the highway.

The NORTH BEACH changes greatly from year to year. Sometimes for an entire summer it furnishes another noble drive, firm and smooth as a floor; but anon the sand washes out, especially in the vicinity of BOAR’S HEAD, make it rocky and uneven. Here is no background of sand-dunes; the waves themselves have thrown up a rampart of rocks, stretching far northward, and forming, in all ordinary weather, an effectual barrier; though in severe storms, the sea sometimes breaks over, with more or less damaging results. Sitting in one of the pavilions here on this rocky ridge a half mile from BOAR’S HEAD, the eye sweeps a scene of Ocean grandeur rarely excelled. Here the open sea dashes eternally against the shore, the green waves, flecked with crimson and purple, rolling proudly in and breaking in thunder and in foam, and the deep blue in the distance flashing as diamonds in the sunlight. Or a gray pall may have settled over the whole — gray clouds above, gray water below, and a sense of awful mystery in the depths.

Oblivious to changing skies and seas, the speckled sand birds scurry, foraging to and fro on the edge of the water mark, where the thin remains of the great waves but moisten the sands, and ripple back to their comrades in the sea. Diving and rising, rocking on the crest of the waves so far out they seem but specks, the larger birds, likewise, pursue their prey; while the occasional report of a gun shows that man, too, is solving the problem of “the survival of the fittest.” A sudden squall, a lost balance, and man himself may be swallowed up by insatiate Ocean, mightier than all. Such a calamity, however, rarely occurs, and fishers and gunners love the sea as a friend.

After all, night is the witching time at this point. One peers out from the little pavilion in the gloaming, to watch for the beacon-lights strung along like golden beads on the horizon. PORTSMOUTH HARBOR, WHALE’S BACK, BOON ISLAND, the great revolving light of the SHOALS, now red, now white, now gone and anon reappearing, and the twin stars of THACHER’S ISLAND far away under the CAPE ANN shore; — all these become distinctly visible as night deepens; while the NEWBURYPORT lights burn as brightly, hidden only by the buildings on BOAR’S HEAD. And the stars blink, and “darkness broods upon the face of the deep.”

Now is the time, if the tide is nearly up, to stroll out from the little shelter, down the rocky slope, to meet the incoming waters. The smoothest rock available serves for a seat. Ah!, there is something weird and yet fascinating in this rush of waters which one cannot see. Only the gleam of each breaker flashes white in a running line, lost quickly in the distance; then gurgling over and among the rocks, the awful flood sweeps back. Nearer and nearer the breakers surge, till the lower rocks are no longer tenable, and the pavilion is again a welcome retreat. Half way up the rocky wall, the flat, “Thus far — but no farther,” turns the tide, and gradually the spell is broken. Now if, by chance, the moon comes up over the eastern horizon, one’s cup of content is full. A glimmer, a luminous speck, a rounding disc, a silvery highway over the deep, a dream of heaven, that is all — but it is all in all.

There is still another point of interest along this beach, to reach which one may walk still northward over the sands, or just back of the sea wall by the cart-path through the edge of the marsh; but go we, rather, back into the town, and come down by a narrow road called “NOOK LANE,” enjoying to the full, the countless wild roses, the clematis and field lilies, the spicy breath of the pines and alders; — then a short, low turnpike, and a stretch of soft sand to the row of fish-houses above high-water mark; and beyond, a new aspect of the sea. On the right, stretching off to BOAR’S HEAD, grown small in the distance, is the open expanse in its grand majesty; but behind, the sea wall is gone, and the sand-hills reappear; while directly in front, sheltered by outreaching rocks still farther north, a smooth surface ripples shoreward, and softly laps the pebbly strand.

This is par excellence, the NORTH BEACH — so designated on the guide-boards; so called by the people, except that now and then an old settler still talks of “going down to the fish-housen.” Here is the chief seat of the fishing interest; here the boats come in and are carried up the sands on rollers to discharge the fish — haddock, mackerel, lobsters, whatever the catch may have been, which are taken in to the fish-houses, and dressed for market, or salted and spread on the flakes. Pollock as well as cod, is much used for this latter purpose. The lobsters are thrown, struggling and snapping, into the great steaming caldron in the rear, whence they emerge, red-hot, a few minutes later, fit for an epicure.

This great mass of rocks, which forms the fishing cove and terminates in a point out in the distant, deeper water, stretches also along the shore northward, and is mostly covered at high tide. The fine, delicate sea-mosses are often found in the pools left by the ebb; and here, if anywhere, one may look for shells. Not but that sea-urchins and other desirable shells are occasionally picked up anywhere along the beach; and after all, it may be that the solitude of this place is the only reason for the greater likelihood. For here, and especially just over these rocks, where another smooth little bay washes another sandy beach, one might remain a day, perhaps days, and meet no human form, nor hear a human voice. Drawing apparently near, but still a mile or two farther on, lies LITTLE BOAR’S HEAD, one of the most charming bluffs, let us venture the assertion, on the Atlantic coast. This, too, is within the boundaries of WINNACUNNETT, though beyond the present limits of HAMPTON — and of this sketch.

Not alone for the summering, is the old town frequented by pleasure-seekers. After beauty and gallantry have vanished, the hotels are still kept open for the fall gunning; the boats are in constant requisition, and the marshes take on the scent of powder. In truth, gunning is a passion alike with stranger and native-born, even small boys pursuing the sport day after day with avidity. Game is abundant, embracing all the scale from the diminutive yellow-legs to the loon, of fourteen or fifteen pounds weight. The happy gunner who brings down a loon or a wild goose, marches homeward with a soldierly bearing, the game slung over his shoulder; but the luckless fellow who snaps at nothing, slinks home across lots.

Both sea and forest birds, game and songsters, abound in great variety; and the transition from gunning to Taxidermy has followed, in several cases, as a natural consequence. One enthusiast, who has made a collection of two hundred and fifty stuffed birds, says: “I have identified 186 species as occurring in this town, 56 of which I have known to breed here. I have nine varieties of hawks, and four of owls. There are nearly 30 more species given in the list of NEW ENGLAND birds, some as common, others as rare or accidental, which may yet be found here.”

The human Aborigine has passed away with the old-time regime; but the feathered tribes of two hundred and fifty years agone, still linger in