By F. Walton McMiller

The Granite Monthly, A New Hampshire Magazine

Vol. XXVII – December, 1899 – No. 6

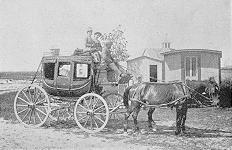

How they got there before

the railway was built

This century began with the stage-coach; it ends with the automobile. Intermediates in the process of evolution are the steam locomotive and the electric car. And the greatest of these is the electric car.

Swifter and more comfortable than the stage, it still allows that intimacy of association, that near knowledge of the people and places met on the journey, which was the chief charm of the old coaching days. The electric road goes where the steam railroad cannot profitably go, and when the necessity arises it equals the speed and strength of its elder brother. The electric car, too, is the poor man’s automobile. Where the owner of an automobile pays hundreds of dollars the less wealthy man can, for as many nickels, own so much of an electric car as will suffice for his journeyings whither he may desire to go.

There is a poetry, a picturesque quality, about travels by trolley such as no other mode of locomotion possesses. Mr. William Dean Howells, as usual a pioneer, has transferred something of this quality to paper of late in his descriptions of rides on the York electric road. Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes prophesied it years ago in that oft-quoted poem, “The Broomstick Train.”

That without his leave they were ramping round,

He called, — they could near him twenty miles

From Chelsea beach to the Misery isles;

The deafest old granny knew his tone

Without the trick of the telephone.

“‘Come here! you witches, come here!’ said he, —

‘At your games of old without asking me!

I’ll give you a little job to do,

That will keep you stirring, you Godless crew!’

They came, of course, at their master’s call

The witches, the broomsticks, and cats and all.

“He led the hags to a railroad train

The horses were trying to drag in vain.

‘Now then,” says he, ‘you’ve had your fun,

And here are the cars you’ve got to run.

The driver may just unhitch his team,

We don’t want horses, we don’t want steam;

You may keep your old black cats to hug,

But the loaded train you’ve got to lug.’ “Since then on many a car you’ll see

A broomstick plain as plain can be;

On every stick there’s a witch astride, —

The string you see to her leg is tied.

She will do a mischief if she can,

But the string is held by a careful man,

And whenever the evil-minded witch

Would get some caper, he gives a twitch.

As for the hag you can’t see her,

But, hark! you can hear her black cat’s purr,

And now and then, as car goes by,

You may catch a gleam from her wicked eye.

“Often you’ve looked on a rushing train,

But just what moved it was not so plain.

It couldn’t be those wires above,

For they could neither pull nor shove;

Where was the motor that made it go

You couldn’t guess, but now you know.

“Remember my rhymes when you ride again

On the rattling rail by the broomstick train!”

Surf Bathing at Hampton Beach

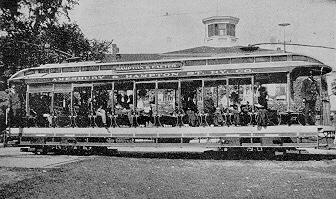

One of the Winter Cars

One of the Small Cars

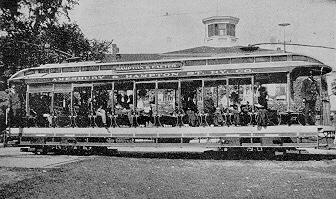

E., H. & A. St. Ry. Co.

Apart from the comfort, pleasure, and profit which the electric car affords to the individual passenger it has a direct and indirect value, both ethical and material, for the communities through which it passes, and for the state and nation whose development it is hastening with such giant strides.

When the stage-coach gave way to the steam locomotive and the iron horse forsook the old turnpikes for more direct roads of steel between important business centers, many towns that had prospered and flourished mightily under the old régime drooped and faded because the steam road had declined to come their way. The attraction was all to the centers, to the accumulation of people and property in large cities. Gradually the farming districts, here in New England, at least, were deserted; the era of abandoned farms came in. The population was practically obliged to concentrate itself along lines of travel and traffic. No industry, not even that of farming, could profitably be carried on at a distance from a railroad line.

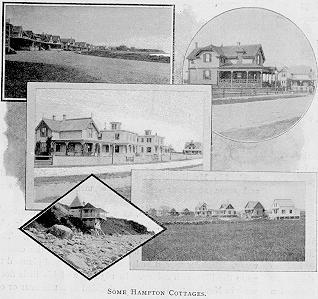

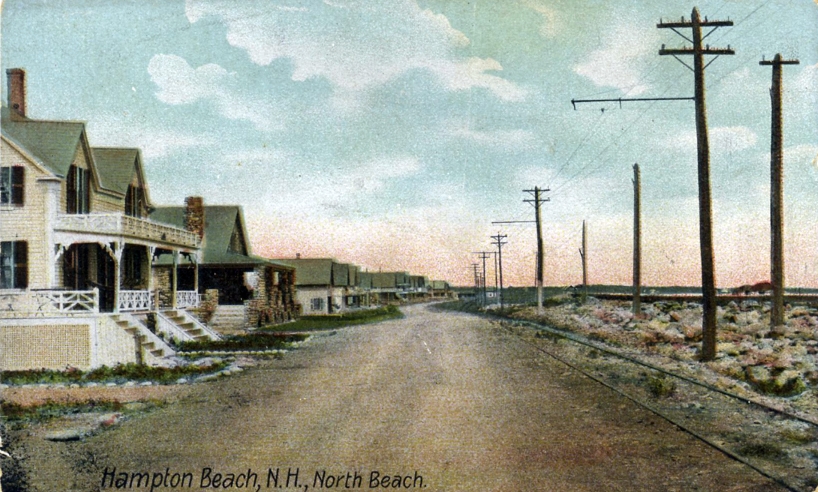

Some Hampton Cottages

Now the electric railroad has come to give back to the country that which the steam railroad took from it; and to make more permanent and abiding the prosperity of the cities, because no city, unless it be a railroad or maritime center, can be long prosperous without a rich country district surrounding it. In this I am speaking of the electric road that connects city with city or town with town, and opens up to the possibilities of rapid transit a section that the steam roads could not or would not touch.

Of the vexed question of competition between steam and electric roads, of paralleling and rate cutting, this is not the place to speak. Nor is it necessary to call attention to the problem of city congestion which electric transportation has done so much to solve. This article was begun with the idea of calling attention to the great good which electric roads can do and have done as auxiliaries in giving quick and cheap transportation across country between points not so reached by steam railroads.

On the Rocks–Hampton Beach

With this as a subject and text, illustrations were easy to find in every New England state, but no better one can be discovered, I think, than the Exeter, Hampton & Amesbury railroad affords. This road, with its twenty-eight miles of track, connects the scholastic town of Exeter in New Hampshire with the bright little city of Amesbury in Massachusetts, passing on the way through the New Hampshire towns of Hampton, Hampton Falls, and Seabrook.

A lively imagination always makes this railroad figure in my mind as a good fairy, rousing to life fair Hampton, slumbering by the sea, and bringing to her twain suits, handsome and rich, Exeter and Amesbury.

Surf Bathing at Hampton Beach

A trip from one terminus to the other in one of the company’s thirty passenger cars is an experience not readily to be forgotten, so rich is it in interest and information, in the beautiful scenes of the present and the redolent memories of the past. And it is quite as much of a revelation, perhaps, to a lifelong dweller in New Hampshire as to a visitor from abroad.

Let us suppose that we are in Exeter on a glorious June day — in historic Exeter with its famous schools, its busy factories, its fine old residence, its handsome streets and buildings. We will wait at the electric car station for a car that will take us south down Lincoln street (Robert T. Lincoln was educated at Exeter). Then we will go through Arbor street and just as the car turns down Front street a glimpse can be caught on the right, down Arbor street, of a great granite boulder surmounted by a bronze soldier. There, our Exeter guide would tell us, is the monument of a fearless soldier, an honest, rugged statesman, a great lawyer, Gen. Gilman Marston.

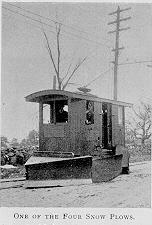

One of the Four Snow Plows

He goes with the Company

Further down Front street, still on the right, and between the car track and the sidewalk is seen another granite boulder with the inscription, “George Whitefield Here Preached His last Sermon September 29, 1770.” The wonderful Whitefield had first come to Exeter twenty-five years before, and though warned by the Rev. John Odlin of the established First church not to poach on his (Odlin’s) preserves had so prevailed upon many of the people that they withdrew from the First church and formed the Second, now known as the Phillips, church. On this 29th of September, 1770, Whitefield stood on the site marked by this boulder and preached to a congregation too large for any church. That afternoon he rode to Newburyport, and next morning he died.

Near by, but across the street, is the recently completed new Phillips church, the seventh of the town’s houses of worship. Adjoining it are the buildings and grounds of one of the best preparatory schools in the world, and one of the best known in America, Phillips Exeter academy. After these are passed the public library comes into view, a handsome structure of cream colored brick, erected by the town as a fitting memorial to its sons who gave their lives for the nation. Then the Baptist church and the famous Gilman house with its gambrel roof and its 150 years of history.

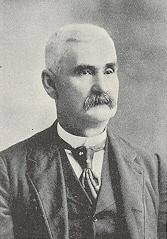

Warren Brown, President, E. H.& A. St. Ry. Co.

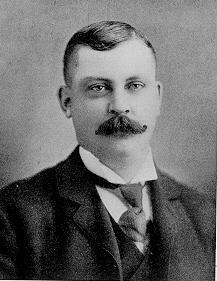

A.E. McReel, Gen. Mgr. and Supt. E., H. & A. St. Ry. Co.

As the car turns to the left down Court square, the town’s principal hotel, the Squamscott house, is seen, while opposite stands the fine old First church, an example of the Colonial style at its best. The First church was founded in 1638 and reorganized in 1698, while the present building was erected in 1798, more than a century ago. Close to this antiquity is the newness of the recently erected court-house. Then come the town hall and the building devoted to the court and register of probate where there are still many ancient records stored in spite of the recent shipment of a carload to the state library at Concord.

Now we turn to the east, into Water street, and are told that President George Washington was once entertained in the brick building on the right, then kept as an inn by Col. Samuel Folsom. Even older is a brown house on the right just as the road turns to cross the river bridge. This was built, they say, in 1658, and Daniel Webster boarded there in 1796, while studying at the academy.

Along Water street, up Town hill and down Main street to the railroad station we go, seeing more old residences, each with a history, and noticing, especially, a little way off Main street, the house where Gen. Lewis Cass was born. And now we are across the river, up High street and off for Hampton. We have not seen Exeter’s famous school for girls, Robinson seminary, nor have we been near the busy factories and shops. So the impression of Exeter which we carry away with us is that of a dignified and richly dressed old lady regarding with fond pride and a caution born of experience a lively boy whose cap bears the monogram, “P.E.A.”

The Exeter Road

The journey to Hampton is through a rich farming country whose quiet beauty and calm prosperity are a joy to behold. Off to the south and southwest are the hills of Kensington and Kingston. To the southeast we look over the valley of Taylor’s river towards Hampton Falls. Ass brook and Bride hill are peculiarly-named landmarks along the way, the latter so called because of a romantic marriage that once took place there in the open air. The reason for the nomenclature of Ass brook local tradition does not state, but it may have been the expression of feeling of one of the parties to the marriage when the reaction set in.

– Part Two –

From Bride hill to Hampton station the car sails along over four miles of level farm land, part of a plateau that separates the “great swamp” in North Hampton from Taylor’s river to the south. Here are a score of splendid New Hampshire homes, substantial buildings on estates centuries old.

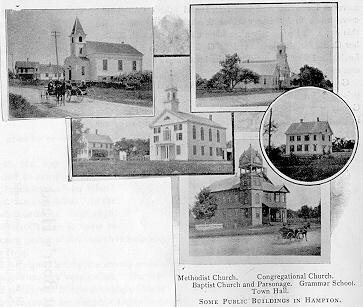

Some Public Buildings in Hampton

Methodist Church, Congregational Church

Baptist Church and Parsonage, Grammar School, Town Hall

Crossing the Boston & Maine railroad at Hampton the rails over which our car passes turn to the south on the old post road and soon we come to the junction with the electric car line from Amesbury to Hampton beach. The electric railway over which we have been traveling was commenced May 19, 1897, and completed July 3, 1897. It has already done much for the mutual welfare of the town which it connects.

Hampton, where we now are, is a farming community with a considerable shore line but no harbor. It has a factory or two, a famous promontory, Great Boar’s Head, and a splendid bathing beach. Rev. Stephen Bachiler, under whose direction it was settled in 1638, was a clergyman who sought a different kind of religious liberty from that dispensed in Massachusetts; just like Rev. John Wheelwright, who had settled Exeter a few months before. It is sad to say that much of Hampton fame in song and story has been derived from her early persecutions of witches and whipping of Quakers as told in Whittier’s stirring verse.

Old Toppan Garrison House

If we are inclined to rest for a moment at Hampton, before going on to the beach, there is at the junction, ready for our purpose, one of the most notable wayside inns in all New England, “Whittier’s” founded in 1755. Just across the road is the Toppan house where lived Col. Christopher Toppan, dignitary of the French and Indian war times, merchant, shipbuilder, and ship-owner.

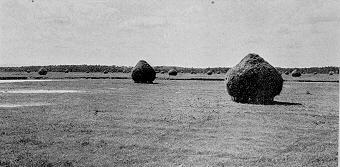

Across Hampton Marshes

Taking the cars from the junction for the beach we see on the right a half mile of meadow and tilled fields, once the “meeting-house green,” because directly across it stood Stephen Bachilder’s first church, built of logs. We go by the church of to-day, the old burial-ground, the town hall, and the “cow common” before we come upon the causeway that crosses the narrowest part of the great salt marsh and brings us to the beach.

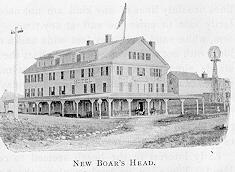

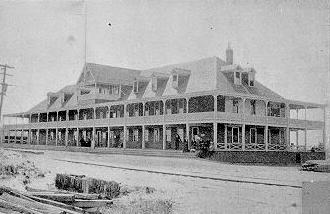

Hampton Beach Hotel

Hampton beach is divided into two fairly equal parts, the north beach and the south beach, by Great Boar’s Head, one of the noted promontories of the New England coast. This is what the geologist calls a “true lenticular moraine or mound of glacial drift.” It is of pyramidal shape, 50 feet high and 1,300 long, thrust out into the ocean like the charging head of a Corbin park boar. In its hardness and bluffness and resisting power it bear no little resemblance, too, to another kind of boar’s head. The head is owned by Col. S. H. Dumas, who successfully managed a hotel there until it was destroyed by fire, and now manages the Hampton Beach Hotel not far away. Cutler’s Sea View house is another prosperous hostelry of the beach.

From Great Boar’s Head, North beach stretches away two miles to Little Boar’s Head in North Hampton. The new life-saving station is its principal attraction. South beach is nearly as long, extending from the Head to Hampton river. It is one of the finest bathing beaches in New England, as safe as it is beautiful. For a mile and a half in length the clean sand bottom gently slopes out for 550 feet with no undertow, and consequently no need for life lines.

New Boar’s Head Hotel

“And fair are the sunny isles in view,

East of the grisly head of the boar.

And Agamenticus lifts its blue

Disk of a cloud the woodlands o’er.

“And southerly, when the tide is down,

‘Twixt white sea waves and sand hills brown

The sea birds dance and the gray gulls wheel

Over a floor of burnished steel.”

All along the line, from Little Boar’s Head to Hampton river, run the rails of the electric road, and their coming has meant more here than anywhere else, from terminus to terminus.

Leavitt’s – North Beach

They have popularized the beach, “resurrected it,” one writer says. Where no visitor came before, a hundred come now; and the enjoyment is as innocent and as wholesome as ever.

Before another summer comes connection will have been made at Little Boar’s Head with the line of the Portsmouth & Dover electric railroad, allowing a trip to be continued through beautiful North Hampton and Rye to the city of Portsmouth.

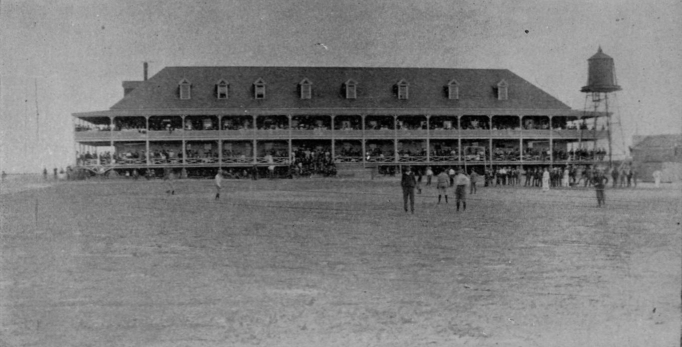

The Casino

The electric railroad management have chosen for especial development at Hampton a large tract of land near the center of South beach, below the cottages. Here has been built a large, commodious, and well-appointed casino, two stories high, with facilities for everything from a temperance convention to a clam-bake, from a fashionable dance to a farmers’ field meeting. There is a kiosk for band concerts, a large bathing house, and a fine baseball ground. From the broad piazzas of the casino a marine view is obtainable seldom surpassed anywhere.

The erection on land adjoining the casino of a large hotel of the first class is a probability of the near future.

Thousands will have the electric car to thank for their opportunity to echo Whittier’s words in his poem to Hampton Beach:

Comes this fresh breeze,

Cooling its dull and feverish glow

While through my being seems to flow

The breath of a new life,

The healing of the seas.

“Good-by to pain and care!

I take

Mine ease to-day:

Here where these sunny waters break

And ripples this keen breeze,

I shake

All burdens from the heart,

All weary thoughts away.”

The old General Moulton House

The Casino on a Sunday Afternoon

But our wonderful electric car trip is a little more than half over yet. We must go back to Whittier’s and start anew for Amesbury. The electric cars follow the old post road through Hampton Falls and Seabrook to the state line. The first object of interest is the old mansion of Gen. Jonathan Moulton, a wealthy contemporary of Meshech Weare and John Langdon, but not of equally blessed memory with them. By a tollgate house, once the scene of great controversy, and in a few minutes we are at the village of Hampton Falls, chiefly interesting at present as being the birthplace of Miss Alice Brown, the author of “Meadow Grass.”

Once, at least, however, on August 10, 1737, it was a gay and festive place when Governor Belcher came up from Boston with a numerous cavalcade, met here the assembly of New Hampshire and made a speech concerning the much disputed boundary line. Having discharged this duty the governor made himself the first of a long line of distinguished men to go a junketing “at the falls of Ammuskeag.” And the dispute over the boundary, which had raged for two hundred years, went right on raging for nearly two hundred more.

One of the Eight-Wheel Cars — E., H. & A. St. Ry. Co.

The most striking object in Hampton Falls is the monument to Meschech Weare, a tall granite shaft flanked by ship carronades, and bearing an inscription succinctly descriptive of the great man’s services to his nation when she needed strong men most. Here is another house where General Washington once slept, being this time on a visit to Governor Weare, and having ridden up from Cambridge. Equally worthy of reverent attention is the house where John G. Whittier, “the good gray poet,” died.

From Hampton Falls the road runs south through the center of the town of Seabrook. At Seabrook Center is a typical country store which is also a street railway waiting-room. A mile and a half further on we come to Smithtown, a pretty hamlet with a neat church. Here the Hampton Amesbury electric road meets a branch that runs up from Newburyport and adds another to the numerous possibilities in the way of divergent trips which our road furnishes by its connections. Here, too, is the recently established boundary line between New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

Looking up North Beach

Looking South, from the Casino

The Leonia

Over the line we go into the old Bay state at the township of Salisbury, traversing Salisbury Plains to Frost’s Corner, where the township of Amesbury begins; south for half a mile, then west along Clinton street; down Market street past the fair grounds, and we ar at our journey’s end; Market square in the city of Amesbury.

There is much to tempt us to linger here where Whittier lived his pure, sweet life, and sang the songs of New England; and where, to view the place from an entirely different point of view, the Pow-wow river, with a daily flow of 180,000,000 gallons, falls 70 feet in 50 rods.

Ball Grounds, rear of the Casino

With such a water power there has, of course, always been manufacturing here. “The first establishments were saw mills and grist mills in 1640, followed in later years by snuff mills, linseed oil mills, fulling mills, a starch mill, and century ago a smelting furnace, where one thousand tons of iron were wrought in a year; anchors, scythes, axes, and other edge tools were manufactured.” Now, to mention just one industry, there are here fifty firms that make 25,000 carriages a year. Then there are car shops and machine shops, woolen mills and other mills, an assessed valuation of property reaching five millions of dollars, and a savings bank with deposits of two millions. It is on the Boston & Maine railroad, and besides the electric road over which we have just traveled, it has others that would take us to Merrimack and Haverhill on the west, or to Salisbury beach and Newburyport on the east.

Looking North, from the Casino

Most of the historic scenes in and about Amesbury are connected with Whittier, whose unpretentious residence stands at the corner of Friend and Pleasant streets, not far from the Friends’ meeting-house. To us, visitors from New Hampshire, there is pride as well as interest in the sight of the bronze statue to Josiah Bartlett, who was born in Amesbury, but signed the Declaration of Independence from New Hampshire. From the top of Pow-wow hill can be obtained a view whose breadth and beauty is altogether out of proportion to the height of the elevation, 332 feet above the level of the sea. Then, if we are not awearied of antiquities, there is to be seen the residence of Thomas Macy, first town clerk, driven to Nantucket in 1659, for harboring Quakers. And we can drink from the famous Bagley well (now prosaically filled by the city water works) of which Harriet Prescott Spofford sang:

We have flung the rein loose many a day,

And paused for a draught from the mossy depths

Of a gray old well by the public way.

A well of water by the public way,

Where the springs make their dark and mysterious play.

“Valentine Bagley sank that well,

A hundred years since, out of hand,

When he came back from the Indian seas

And his wreck on the fierce Arabian strand,

Where the airs like flames about him fanned,

And the ashes of hell was the burning strand.”

The Merrimack at Amesbury, Mass.

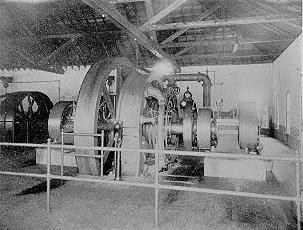

A unit of the power plant

And now, having enjoyed a day packed full of varied interest and pleasure, let us search out the courteous and capable superintendent of the road, Mr. McReel, at his office in Exeter, and learn from him of the plant which has carried us in its cars so swiftly, so safely, and so comfortably on our long jaunt.

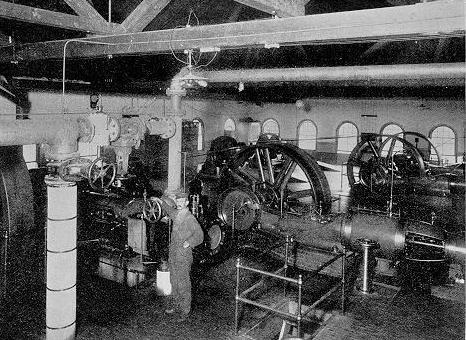

Mr. McReel might say something like this: The power station and plant is centrally located in Hampton about two and a half miles from the junction on the line to Exeter. The lower building is of brick and is 100 feet by 80 on the ground. It is divided by fire-proof walls into the boiler room, the power room, and the pump and condenser room.

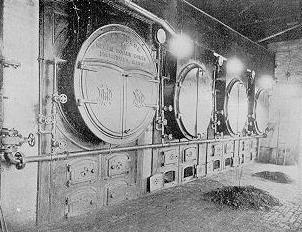

Boiler Room

In the boiler room are four 72-inch by 18 feet tubular boilers of the best construction. All the feed water connections are so arranged that any one boiler can be fed independently of the others with either heated or cold water. Two of these boilers are in daily use for the railway, and one is added when the lights are put on. The fourth is an auxiliary to be used in case of need.

In the power room are three 185 horse power, high speed, Buckeye engines, of 15¼-inch cylinder and 24-inch stroke. When doing regular service they are run at 160 revolutions per minute. Two of these are used for the car service; the third one for lighting service, and is run from 4 P.M. to 12 midnight. The car service engines run two Keystone generators, each of 125 kilowatts and 550 volts. The light service engine has a generator of 2,300 volts for the incandescent lights, and one of 4,000 volts for the arc lights, of which 80 are used in Exeter.

Engine Room, Power Station, Hampton

There is also, a new Cross compound condensing engine of 400 horse power. The high pressure cylinder is 16½ inches in diameter with a 30-inch stroke, and the low pressure cylinder is 30½ inches in diameter with a 30-inch stroke. The engine is directly connected with its generator. That is to say, no belts are used as in the other engines. This generator is of 250 kilowats and 550 volts. This compact and powerful engine and generator, practically one machine, is so constructed that it can be run by either of the cylinders, if, from any cause, the other becomes disabled. This engine was put in as an auxiliary power to the two service engines, and is intended for use in case of accident or on heavy traffic days to assist the two regular engines.

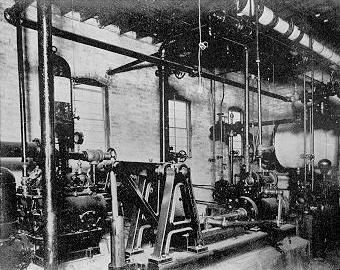

The compound condensing system of Mr. L. C. Lamphear of Boston, capable of caring for the exhaust steam of 1,400 horse power, has been installed. It takes the exhaust from all of the engines, adds some live steam and with it heats the feed water for the boilers. After doing this work the exhaust steam goes to the condenser, where, in a 26 inch vacuum, it is condensed to water. This rapid condensation of the exhaust, in theory, will relieve each cylinder of 14 7-10 pounds per square inch of back pressure. In actual use, day by day, it will certainly save, at least, 12 pounds per inch, and by the consequent gain in the engine service will save from 20 to 25 per cent in the fuel consumed. All of the connections for this condensing system are in duplicate, so that in case any valve or pipe is disabled, it can be “cut out” and repairs made while the condenser is still doing its work.

The Pump Room, Power House, Hampton

The heater for the feed water, the condenser, the duplicate feed pumps, and the fire pump of one thousand gallons per minute capacity, are in the fire proof pump room.

In the power room there is a steam gauge that registers the pressure for every hour the boilers are in use, and another showing the present pressure. By meters the engineer knows how much power his machines are producing, and by ammeters he can tell how much is being used on any one of his three circuits.

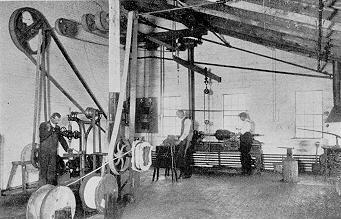

A Corner in the Repair Shop

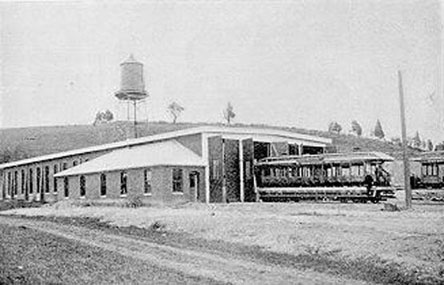

The car barn is of wood and is 215 feet long by 50 feet wide. It can shelter twenty-four cars at one time on its four tracks. It has six pits with cemented bottoms and brick sides for use in cleaning the running gear under the car floors, and forty-eight feet of floor in front is of cement, where the cars are washed. At the rear, and separated from the rest of the building by a fire proof wall, is the completely equipped repair shop and the stock room with its powerful motor and stock of lathes, drills, and other machinery.

The whole building is covered with metal shingles and fitted with the dry air, automatic sprinkler system. Water is supplied from an artesian well 154 feet deep, 140 feet of which is in rock.

The car barn at Amesbury is of brick, and in size and arrangement a duplicate of that at Hampton, except that there is no repair shop attached. At this writing the road owns twenty-six passenger cars, with three more building; two flat cars, and one box car for freight, and four powerful Taunton snow plows. Among the passenger cars are six fourteen seat, eight-wheel summer cars, equipped with powerful air brakes. At each side, by each seat, is an electric push button, by which the passenger can notify the conductor to stop the car. These cars move with the speed and steadiness of a passenger car on a steam railroad, and it is of this model that the three new ones are being built. Another style is a combined summer and winter vestibuled car, especially adapted for the use of clubs and trolley parties. All the company’s cars were built by the Briggs Car Company, of Amesbury.

Power House and Car Barn at Hampton

Amesbury Car Barn

The company’s twenty-eight miles of track are laid with the heaviest steel rails, and so well ballasted as to be able to carry any railroad train in the country. The best materials and latest fittings have been used in every part of the equipment. Telephones have been placed in all of the offices, at the terminals, and at every turnout. The line is a regular mail carrier.

In short, the Exeter, Hampton & Amesbury Street railway is a model. Its location, its equipment, its management are beyond criticism, and the man who deserves the praise and is the principal owner of the company, is Mr. Wallace D. Lovell of Boston, who planned all this and put the right men in the right places to carry out his plans.

NOTE. — For most of the facts and some of the phraseology in this article, credit is due to an exceedingly interesting and comprehensive guide book issued by the company and published by the Rumford Printing Company.

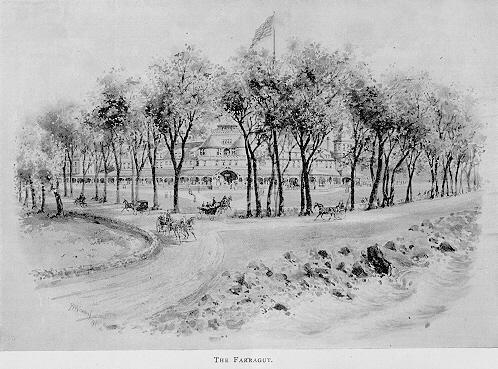

The Farragut at Rye Beach, N.H.