By Eva A. Speare

Second Printing — 1969

Courier Printing Co., Inc., Littleton, N.H.

Strawbery Banke according to old picture

INTRODUCTION

This booklet is a valedictory to childhood’s remembrances of one who was born about a century ago, near the seacoast. One recalls the rides in the beach wagon drawn by a span of strong horses over dusty roads to the shore. Seats were lengthwise along the sides, and the supplies for several days were on the floor between the seats.

After driving from early morning until mid-afternoon, the plank road across the marsh was welcome with the ocean in sight. As the cottage was approached, everybody walked while the wheels sank deep into the sand and the horses pulled mightily to the doorway.

The beach was occupied by several cottages, and two white houses called hotels were in the distance. Otherwise the beach was ours. Every child possessed a small wooden shovel that supplied the one plaything needed.

When the tide was out, what fun to pile the wet sand in circles, called forts. Every child built several. Also wells were dug about a foot deep, scattered zigzag along the beach. As the tide rolled in, everyone watched to shout when his fort fell first, then again if his well filled first, also whose fort stood longest and whose well remained to the last. Racing with the surf before the water wet our feet was more fun.

After the tide beached the dory of a lobsterman, father took his market basket to purchase lobsters. The aged fisherman had built a fire on the sand and a large, black caldron filled with sea water had been hung to boil over the fire. Two red lobsters would fill the market basket, which was about twenty-five inches long, and the price was fifty cents for the two. The lobsterman plunged his hand into the boiling water to lift a lobster without apparently feeling pain, to my childish astonishment.

At present with the cottage cities, crowded beaches, ice cream and candy kisses, pleasure motor boats, airplanes, boulevards and lines of automobiles, today is a new world. Yet the beauty of the sea and sky, the breaking waves at high or low tide, and the cry of the gulls remain unchanged.

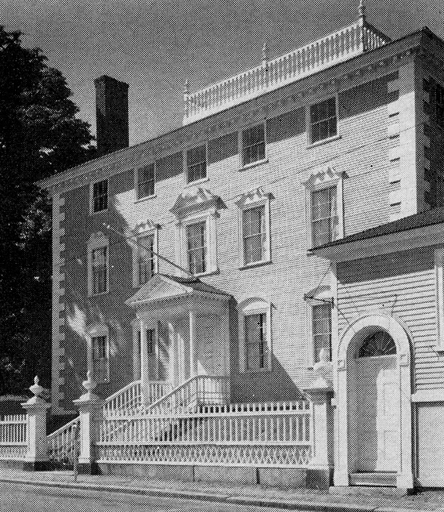

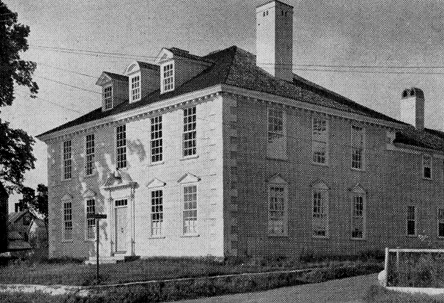

Moffat-Ladd House, 1763. Special features: design of fence sith urns, dentiled doorway, “broken” pediments above windows, and balustrade on roof

I

Geology Of The Seacoast

The seacoast of New Hampshire is a summer playground for thousands who love the atmosphere by the sea. Furthermore, enclosed within its eighteen miles are the evolutions of Mother Nature, the fascination of its historical lore and the exceptional beauty as well as the quality of its architectural heritage.

The geological record was summarized by the late Professor James W. Goldthwait of Dartmouth College: “The seacoast has had its ups and downs, its ins and outs.” Much of the beginning of this story should be assigned to the credit of another geologist, the late Louis Agassiz, who in 1870 was proving his theory about ice ages by observing cracks and scratches on the foothill of the White Mountains that preserves his name, Mount Agassiz in Bethlehem, New Hampshire.

While looking out to sea today it seems incredible that 14,000 years ago North America was buried beneath an ice sheet, about one mile in thickness, beginning at the North Pole and extending southward to the 40th parallel of latitude.

For the benefit of possible young readers, it may be well to explain the cause of this peculiar condition. We turn to the astronomers who have discovered that the axis of the earth is inclined twenty-three and a half degrees to its pathway around the sun; also that the axis wobbles so that the poles describe a circle that requires 26,000 years to complete.

When one of the poles is tilted away from the sun, the temperature becomes so intensely cold that everything freezes. Storms accumulate ice in layers that form a glacier a mile in thickness.

In the course of thousands of years the pole tilts around into the sunlight and the temperature gradually moderates until the climate becomes torrid, which accounts for the coal fields that lie beneath the surface of Alaska.

Scientists believe that the present temperatures will become warmer during the following 2,000 years. The pole star will be a constantly changing beacon for sailors while the pole moves from star to star.

The “downs” of the seacoast are the result of the last ice age. When the glacier grew thicker, it pushed southward. Every elevation in New Hampshire was sliced off, with the exception of Mount Washington. These granite crags were crushed into boulders of every size and shape, buried deep into the ice and dragged many miles.

In due course the pole circled into the sunlight. The moderating temperatures began to melt the southern mass of the glacier.

The colossal weight of ice depressed the land and the cold condensed the ocean until their levels sank between two and three hundred feet. Relieved of this burden, the continental shelf which extends under the sea about one hundred miles, snapped upward, rolling the melting ocean inland to the line of Rochester in New Hampshire. Along this ancient shoreline, hills of glacial drift, called drumlins and sand dunes, now rise two hundred feet in height.

Temperatures continued to rise until the continent, far into Canada, was free of ice. This northern area began to tilt upward, rolling the ocean eastward beyond the Isles of Shoals.

A legend that was told to white men by Indians, related that “long, long ago there was a big noise, then the sea rushed in.” Probably a violent earthquake changed the Shoals from headlands to islands.

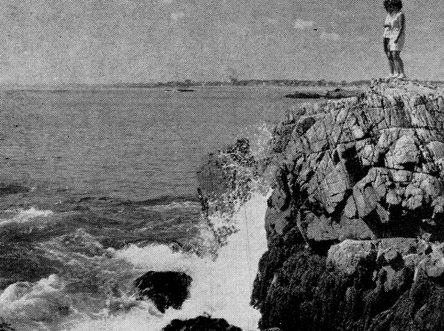

Finally, about 3,000 years ago, the seacoast settled to its present level, forming the long, sandy beaches that are separated by promontories or granite ledges that are scarred with glacial cracks and scratches.

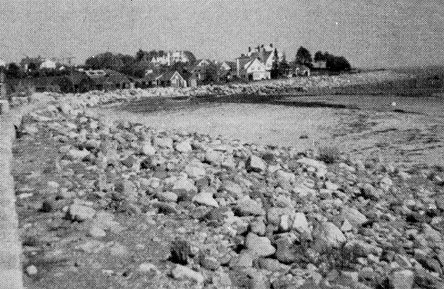

How daily tides and storms change the shoreline is astonishing. Tons of sand wash in and out. Violent breakers wash water-worn pebbles from the bed of the ocean over the shore, called “Shingle Beaches.”

A shingle beach where water-worn pebbles cover the shore

Geologists believe that a deep break in the crust of the earth, called a fault, begins far out in the continental shelf and extends inland many miles beyond the vicinity of Rye. This slips from side to side with the weight of tons of silt that are carried into the sea by the rivers. This upsets the balance and earthquakes result.

In his diary, Samuel Lane, a pioneer settler in the Town of Hampton, describes “the great earthquake of 1727” and the “terrible earthquake of 1757.” Chimneys toppled at the ridgepoles. Houses and barns swayed yet did not collapse because of their balloon construction, meaning that the frames could expand slightly because the timbers were joined with wooden pins.

Slight earthquakes occur on the average about every twenty-five years in New Hampshire.

Such were the forces that Mother Nature combined to create the “ups” and “downs,” the “ins” and “outs” that evolved this playground along the seacoast of New Hampshire.

II

The Lore Of History

So far as is known today, the first Europeans to land in New Hampshire were Norsemen. The proof is found in Runic inscriptions on a rock in Hampton. About 1902 an article was published in a newspaper in Philadelphia in which a judge stated that his ancestors found this boulder over 300 years ago on the grant of land that they received from the King of England. This article attracted the attention of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

When the Town of Hampton was planning its Tricentennial in 1938, two archaeologists were requested to search for this old landmark. With the knowledge of an “old timer” in Hampton, this Norse boulder was relocated near the surface of the ground beneath a pile of rubbish.

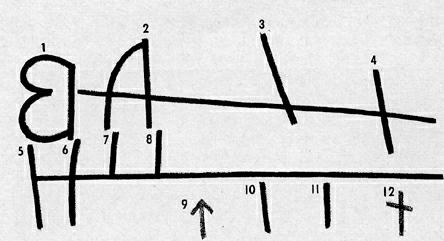

Norse Boulder at Surf Side Park, 1043 A.D

On its side were chiseled strange characters and other figures. The pattern was clearly marked with chalk and photographs were sent to a skilled interpreter of the Runic Alphabet, Olaf Strandwold of Prosser, Washington.

In his book, “Norse Runic Inscriptions Along the Atlantic Coast,” published in 1939, Mr. Strandwold interpreted the runes of this inscription upon the boulder in Hampton to read, “Bui Reis Stein.” The translation is “Bui Raised Stone.” Bui is the name of a family in Norway who won battles for the Vikings in the tenth century A.D.

Runic inscription on the Norse Boulder

The Runic Alphabet contains sixteen characters: each represents a sound and also a number. The date of an inscription is determined by the arrangement of the runes. A horizontal line that is cut across a certain number of runes designates an appeal to the god Thor. The date of the boulder in Hampton is 1043 A.D. Before Mr. Strandwold visited Hampton, the Norse Rock was called Thorvald’s Rock. Thorvald was the son of Lief the Lucky, discoverer of Vinland in 1003. The rock in Hampton does not exhibit the description of the site where the Saga tells that Thorvald was killed by Indians.

In the year 1477 Christopher Columbus visited Iceland to study about navigation from the experience of the Vikings. The maps that he saw there convinced him that he would arrive at India by sailing west across the Atlantic.

Martin Pring In 1603

The first recorded English navigator to visit the coast of New England was Martin Pring in 1603. In the 15th century, sea-worthy schooners were designed, and fleets of fishermen visited the Grand Banks and probably landed upon the Shoal Islands to salt their catches in the summer months. The word shoal meant fishing grounds in that century.

Martin Pring was furnished with two vessels by merchants of Bristol, England, with instructions to explore coastal rivers and hunt for sassafras, then considered the cure for French-pox and other diseases. He sailed up the Piscataqua River but historians disagree about the sassafras. Writers declare that he loaded both boats with these roots. Others state that he did not see a sassafras tree.

Samuel Champlain In 1605

France was mindful of the New World. Samuel de Champlain sailed along the coast of New Hampshire in 1605. He is believed to have spent a night in the harbor of Hampton River and perhaps in the small inlet at Rye Harbor, since both are found upon his map of the shore.

Captain John Smith in 1614

The famous explorer, Captain John Smith, was commissioned by merchants in London to look for gold, copper and whales. He was not a miner or a fisherman. Rather, he selected eight of his crew of forty-five men to sail with him in a small boat into every inlet and mouth of a river along the coast. When he returned to England, he presented his now famous map to prince Charles who named his discovery New England.

Pannaway

Many adventurers were voyaging to New England, among them David Thompson who selected a bay for a settlement. The Aristocratic Fishmongers Guild of Plymouth, England employed him to outfit the ship Jonathan to establish a fishing village at his bay which he named Little Harbor. His village was called Pannaway, the first permanent settlement in New Hampshire, in 1623, now called Odiorne’s Point. With possibly ten men, increased later to thirty, he erected dwellings and other necessary buildings, and set up salt works and frames upon which the cod and haddock were salted and dried.

In his book, Ports of Piscataqua, William G. Saltonstall tells about the fleet of vessels that these fishermen soon were sailing along the coast, consisting of six great shallops, thirteen skiffs and five fishing boats with sails and anchors, within less than ten years. Every fisherman was supposed to possess the knowledge to build his own boats.

Dover Point

In that same spring of 1623 two brothers, William and Edward Hilton, set up their fish flakes on the Piscataqua River at Dover Point. Their settlement was also permanent, and to this day the dispute remains unsettled about which arrived first, David Thompson or the two Hilton brothers.

Briefly, the story of the seacoast of New Hampshire opens with visions of a square sail, striped with green and white, bearing the high prowed open hull of a Norseman’s ship over the breakers, with the shields of the oarsmen glistening in the sun along the bulwarks, a thousand years ago.

III

Exploring The Seacoast

Thousands of people prefer to look out over the ocean rather than inland among the mountains. Exploring may be only a stroll at low tide along the sands, collecting sand-dollars or seashells of many colors and shapes.

For those who own a cottage on the sand dunes or enjoy their annual vacation at the shore, exploring may arouse their curiosity about the origin of local names or the historical background of the locality.

This booklet briefly guides to landmarks that date to the long ago. Also noted are features of the landscape, local folklore and events that stir the imagination. One important fact of interest is that the State of New Hampshire claims the line that meets the sea.

Town of Seabrook

The southern border of the Seacoast is at Seabrook, one of the divisions of the 100 square miles that belonged to Hampton, first settled in 1638, then incorporated as a separate town in 1768. Inland across the marshlands is the thriving, industrial village along Route U.S. No. 1.

Along the beach are summer homes and a harbor, recently dredged, with a pier and floating dock. At Seabrook Beach there is access to the shore for the public, with a small area provided. Here anyone is welcome to stop for a picnic or a dip in the ocean.

Up the coast a cottage development between the Ocean Boulevard and the shore drive has named its streets for cities and towns in New England. Approaching the Hampton River, Woodstock and Plymouth

Streets extend to the shore. At this exit, between the cottages on either street, deep down in the sands, is a landmark called “Bound Rock” that marks the site of a long controversy.

This begins before New England was occupied by Englishmen. The King made the mistake of granting this territory to two different companies: The Massachusetts Bay Colony with its boundary line at three miles north of the Merrimack River; John Mason of Plymouth, England also received a large tract which he named New Hampshire with his boundary line in the middle of the Merrimack River, thus overlapping into Massachusetts.

In 1638 Massachusetts granted the Town of Hampton within the territory that John Mason claimed. In 1639 Massachusetts granted the Town of Salisbury on the north bank of the Merrimack and far into New Hampshire to the present town of Hampstead.

Both colonies assessed taxes for the settlers of Hampton. When these grantees refused to pay double taxes, Massachusetts arrested them and confined them in the dark jail at Salem, in the Bay Colony.

Finally the Court appointed a surveyor named Shapley to draw the boundary line between the two towns. Mr. Shapley found a ledge in the middle of the Hampton River which he marked H.B. 1656 to designate Hampton Bounds. He named this ledge “Bound Rock.”

While another century passed, the tides and the winds filled the bank of the Hampton River with ten feet of sand that buried Bound Rock and moved the bank 300 rods northward. Meanwhile the line between Massachusetts and New Hampshire was fixed at the three mile limit northward of the Merrimack River, and Governor Benning Wentworth granted a new town called Seabrook in 1768, between Salisbury and Hampton.

Cement bulwark above Bound Rock

Both towns disagreed about the boundary line. Seabrook claimed that the Hampton River marked its northern boundary. Hampton declared that Bound Rock determined its rights. With the assistance of the memory of an aged surveyor, Bound Rock was excavated and marked H.B. 1856 and again marked in 1861.

Within the present century a cottage development encroached along Seabrook Beach with two of its streets named Plymouth and Woodstock, on the drifting sands. The Highway Department of New Hampshire again found Bound Rock and to protect it from burial, an octagonal cement bulwark was erected from the ledge up to five feet above the surface of the sand, now visible between Plymouth and Woodstock Streets. In 1938 the Town of Hampton requested that the Superior Court of Rockingham County set the line between Seabrook and Hampton.

Finally, after 325 years from the beginning of this boundary trouble, in 1953 the Court reviewed the evidence of old records and decreed that Bound Rock and the Shapley line, now marked by a flat stone where the tree once stood with B.T. upon it for Bachiler’s Tree, is the legal line between Seabrook and Hampton.

Neither town is pleased with this decision. Seabrook loses thousands of tax dollars. Hampton must now provide schools, police protection and most problematical, a water supply. Thus in the words of the poet, “Times makes ancient good uncouth.” Bound Rock is, indeed, a landmark.

Town of Hampton

The bridge over the Hampton River is the entrance to Hampton. Certainly the landscape is vastly changed since three hundred and twenty-five years ago when the few Puritans joyfully landed among the forests and marshes. Joyfully, because they had been granted 100 square miles of territory by Massachusetts, although within the claim of John Mason.

Already their church was organized with Rev. Stephen Bachiler, minister, then seventy years of age with vitality that sustained a notable activity another thirty years.

The name Winnacunnet was selected for their town, meaning “Beautiful Place of Pines.” Truly appropriate, because forests of pine and oaks extended to the very shore. Along the bank of the Hampton River and further inland their oak-framed houses and barns were erected. The harbor was busy with schooners for the coasting trade and fishing fleets.

But trouble arose. Within the religious tenets of these Puritans was a conviction that the Devil bewitched persons who willingly held communication with him. Several men and women were accused of familiarity with the Devil, but their cases were dismissed by the Court.

Unfortunately Mrs. Eunice Cole was convicted of witchcraft, sentenced to be flogged, then confined for life in the jail at Salem.

The evidence seemed to prove that two young men were drowned when she caused their boat to overturn. A farmer testified that his two calves died after eating Goodwife’s grass as she predicted they would. A group of young people were drowned after she warned them that a storm was gathering. So, “Goody” Cole was a witch.

Rather than allow her in their town, the citizens paid eight pounds annually for her board.

As years passed, repeated petitions were offered for the release of this unfortunate woman, when her husband was too ill to be alone and after he died. Once she was allowed to return to her home but was again committed to the jail. Finally the Town of Hampton refused to pay board and she was unable to find the money. She was released and her neighbors were instructed to support her. Hungry and cold, the poor woman died and was buried beside a road with a stake through her body to prevent further witchery.

When the Tricentennial celebration was planned in 1938 by the Town of Hampton, a group of citizens determined to remove the stain from the memory of Goody Cole. A resolution was voted at the annual town meeting on March 8, 1938, restoring Eunice Cole to her rightful place as a citizen of Hampton.

All official documents pertaining to her case were to be burned and the ashes and soil from her last home would be placed in an urn and buried in the ground that the selectmen would designate.

On August 17, 1963 a monument was dedicated to “Goody” Cole at the Meeting House Green Memorial Park in Hampton. Among the Puritan families are many well known names. Perhaps most famous was Robert Tuck whose descendants became prominent in educational and legal positions. On April 30, 1938 the last member to leave a name both at home and abroad was Edward Tuck who died in Paris, France. He accumulated a fortune in banking. Among his generous benefactions to Hampton was a fund to develop the Tuck Athletic Field for young people and assistance in creating the Memorial Park which he paid to upkeep until it was taken over by the town.

He presented the Tuck Historical Building in Concord, New Hampshire and the Amos Tuck School of Business Administration and a residence for the President at Dartmouth College. Abroad, his gifts included collections of tapestries and porcelains, restorations and maintenance of a magnificent hospital.

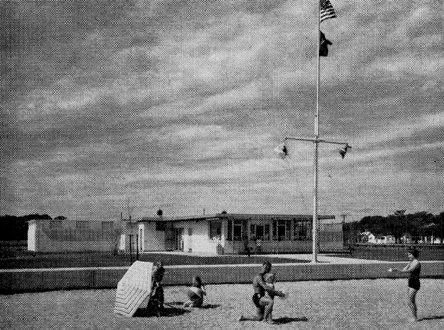

Hampton Beach on a mid-summer day

Hampton Beach

The Town of Hampton was 200 years old before the beach became a vacation attraction. The wide marshes threaded with winding creeks were a risky barrier. Plank roads with heavy timbers laid crosswise of the pathway rumbled and sagged when wagons rolled over them, yet made a passageway to the shore.

Late in the summer months farmers cut the tall grass and skillfully piled it upon “staddles” as the circular foundations of wooden posts were named. These pointed haycocks added a picturesqueness to the landscape over the level marshes until freezing weather congealed the surface. Then this salt hay was garnered into special mows in the farmers’ barns to be fed to cattle in careful rations that provided natural salt when mixed with regular hay feedings. Grandparents relate that only four small houses stood upon the sands at the beach a century ago. Yet the enterprising David Nudd had erected a small hotel, on the highest lot of the Great Boar’s Head, which he advertised to be “exclusive and fashionable.”

Haycocks on the Salt Marshes

On the North Beach Thomas Leavitt opened his large farmhouse to traders from “up country” who came with their four-horse drawn wagons to purchase salt cod that was a staple winter food to sell in their country stores. Fishing and salt works had become a prosperous business all along the coast. At every inlet the small shingled fish houses and the fishing boats were the trading centers with both cod and lobsters in demand.

Sea bathing became popular with many devices for shelter while changing wet costumes. People who owned the canopied top carriages called surreys dropped the curtains and changed within their narrow accommodations. Others set up temporary tents.

The word costumes is used advisedly, especially for women. By the standards of the period, no “respectable woman” would display an inch of flesh from her neck to the soles of her feet “if she possessed an atom of modesty.” Black, long stockings, bloomers, shirt waists and rubber caps transformed the figure into startling proportions. Men did not wear socks, but long overalls and shirts were the rule.

After 1850 the railroad from Boston to Portland brought summer boarders, rapidly increasing the number of hotels. Then trolley cars in the last decade of the 19th century transformed Hampton Beach to its present popularity. The arrival of the automobile demanded highways along the shore. In 1907 the Ocean Boulevard was completed by the State with its stretch of fifteen miles of unobstructed views of the Atlantic Ocean.

Older residents will recall the bridge over the Hampton River, claimed to have been the longest wooden bridge in the world, now replaced by the high steel bridge that touches Hampton Beach. Here on either side of the Boulevard the State of New Hampshire has reserved a spacious State Park for public use.

About seventy years ago a precinct of the Town of Hampton was established at the Beach. Among the regulations of an old contract, no liquor was to be sold at the Beach for a period of ninety-nine years which is one of the reasons that Hampton Beach is a safe area, to quote the testimony of a prominent town official.

The southern coast line is controlled by the State. Activities of many varieties are enjoyed, such as band concerts, bathing during daylight hours, police protection, parking, life guards and commercial facilities.

New Hampshire Marine Memorial

The Marine Memorial stands above the seawall, a beautiful, mature woman’s statue gazing over the waves, a reminder of the soldiers and sailors who have been lost at sea in defense of their country. Here one pauses to pay reverence or possibly to read the name of a relative or friend upon the memorial tablet.

The Great Boar’s Head looms ahead, a rocky drumlin that extends boulders far into the waves. Summer cottages occupy this elevated promontory that is approached by a circular drive from the Boulevard.

Hampton is a summer community of unpretentious homes where thousands of families enjoy safe and happy vacations along its four miles of seashore.

Sixty years ago the Hampton Water Works Company, consisting of the President William H. Jacques of Little Boar’s Head and eight associates, installed an adequate supply of pure water for the Beach in the brief period of fifty-two days. This meant constructing four miles of eight inch pipe and many branches of smaller pipe lines.

The driven wells are a mile from the shore, and the water formerly was pumped to a stand pipe by engines equipped with gasoline or electric power for safety should an emergency occur.

Great Boar’s Head from the air

At the Great Boar’s Head, the Ocean Boulevard and Routes 101-C and 101-E converge. The latter is named Winnacunnet Road between the Beach and Hampton Square. To find Norse Rock, drive up this road, about a third of a mile from the Beach, and watch closely for the sign “Surf Side Park” on the right.

Enter this Park on Arcadia Avenue, turn right to TThorvaldAvenue and left to Emerald Avenue. On the right side of Emerald Avenue on the lawn between two cottages, at the surface, is Norse Rock. [Ed. note, 2003: The Norse Rock is now on the Meeting House Green at 40 Park Avenue, Hampton, NH.] One wonders if this scratched boulder was not actually at the coast line 1,000 years ago.

Continuing to explore beyond the Great Boar’s Head, the United States Coast Guard Station may be visited. Here a crew of thirteen experienced seamen watch constantly for boats in distress. The popularity of sailing keeps the guards busier through the summer months than in fall or winter. Their greatest aid is radar, yet their equipment includes every modern device for rescue at sea.

The North Beach becomes more rocky. Here a high cement seawall, broken frequently by stairways to the sands, protects the Boulevard. In the fall and winter months the breakers dash with such violence upon this curved shore that rounded pebbles of dangerous dimensions are tossed over this wall and the highway is closed to traffic.

As the Little Boar’s Headland in the Town of North Hampton is approached, a rampart of large pebbles lines the highway which was washed from the bed of the sea across the Boulevard during the tropical hurricane of 1938. Bulldozers pushed this invasion of rocks aside to form a protecting seawall today.

Such pebbles tangle with a tough seaweed locally named “Leather Aprons.” This grows with dark brown, glossy strips about six feet in length, eight inches wide and an inch thick with crinkled edges.

Little Boar’s Head

Up the curve to Little Boar’s Head several old fish houses are noticed, before passing the famous rock gardens near the highway, flourishing with brilliant colors under the dampness of the fog.

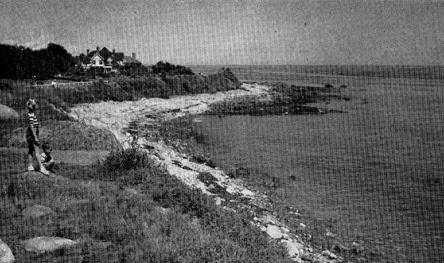

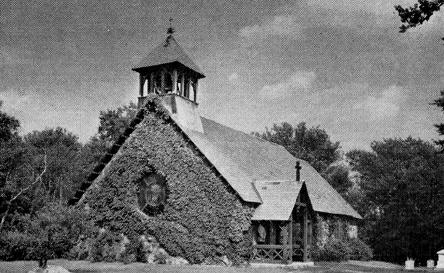

The view at the top of Little Boar’s Head is magnificent — a far and wide seascape with the Isles of Shoals at the horizon. No wonder that wealthy residents selected this section for summer residences. Chapel Road leads inland to the Fuller Rose Gardens, passes Union Chapel, and along a narrow pathway the famous St. Andrews-by-the-Sea is found, the scene of many fashionable weddings. Sassafras trees shade this drive with unusual beauty.

A century has passed since the first summer hotel was opened here by John Colby Philbrick. Two years later the famous Admiral Farragut was a guest and the hotel was named the Farragut House. In 1882 this first hotel burned but was immediately replaced, including the name. Frequented by notables in government and social prestige, the house gained and still maintains its record of the fashionable hotel on the shore of New Hampshire, with its surroundings of spacious lawns and unsurpassed ocean view.

St. Andrew’s Chapel at North Hampton

The cliffs rise to Fox Head Point and the Rye Ledges, then descend to the sands of Rye Beach. Within the marshlands is Eel Pond filled with white water lilies indicating that this water is fresh. Names of pioneers and important events cling to the following ten miles.

Jenness Beach

Fishermen’s Huts at North Hampton

The name of Francis Jenness is perpetuated from the days when he cleared the forest, pulled the stumps, and cultivated wheat. On Cedar Swamp Run he built his dam and the grist mill that ground his wheat into flour, then baked bread and sea biscuits that he sold in markets in Boston and Saco. Many tales of local history are perpetuated in the manuscripts of a descendant, John S. Jenness, dated 1878.

Exploring old roads inland that lead to the Old Post Road, now Route 1, (among them the South Road and Central which passes through beautiful Rye Village), adds variety to this landscape. About 1800 Whitehouse Brown erected his homestead. He is said to have acquired his nickname because he was the first owner to paint his house white instead of the usual red or yellow that was a compound of whale oil and either red or yellow ocher that was mined in Maine.

Drive slowly along the Boulevard to find the sign “Old Beach Road” on the right, now a semi-circle to Lock’s Neck. Here is a small house with a mansard roof that displays a sign on its front door, “Cable House.” In 1874 this house was erected to receive the “Direct Atlantic Cable,” the first to stretch from the U.S. to Europe. It is a fine guest house today.

On the afternoon of July 14, 1874 crowds assembled to watch for the steamboat Ambassador while the cable was landed, but fog prevented. Lest this unusual event be missed, many remained into the night. Realizing that all were hungry, Mrs. Lock and neighbors fried doughnuts and brewed coffee many hours, a kindness that has been remembered almost a century.

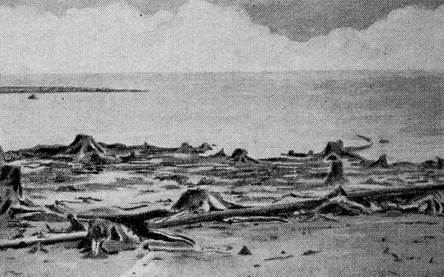

The old Lock House stands at the junction of the Beach Road with the Boulevard. Since the Cable House was not then ready, the cable was actually received at the Lock homestead on the following afternoon. The cable was laid over the stumps of the “Drowned Forest” which extends out beyond the line of low tide and is seldom visible unless a storm has washed away the sand above it or an unusually low tide discloses it.

A “drowned forest” at very low tide (drawing)

Professor Goldthwait believed that these forests grew a thousand years in the past and their stumps have been preserved by sand and salt water. Not only on the Rye shore but at Odiorne’s Point and on into Maine and Nova Scotia other drowned forests are seen.

The story of Lock’s Neck or Point begins when John Lock migrated from Yorkshire, England about 1644. The Piscataqua Tribe of Indians resented the loss of their hunting grounds to the settlers and many sudden raids resulted, such as the Breakfast Hill and Brackett’s Lane.

Clever John Lock outwitted the Indians so often that they kept an eye out for an opportunity to kill him. While he was alone reaping grain in his field, he carelessly leaned his gun against a rock. Suddenly a band of the redskins ran between him and the gun. Although they fatally wounded him, before he fell, he slashed the nose of one enemy. Later in Portsmouth this disfigured Indian told the story about the last fight of John Lock.

The descendants of this brave pioneer have gathered at his old homestead for the annual meetings of the Locke Family Association. The name of Lock’s Point, after two hundred years, was changed to Straw’s Point when Ezekiel A. Straw, Governor of New Hampshire in 1872-1874, erected the first summer home well out toward the shore on the Point.

Back on the Boulevard, busy Rye Harbor is approached, once the small inlet that Champlain included on his map of the shore. Before crossing a small bridge, a driveway leads to Little Neck where a fishing village lies along the shore. Driving around a curve on the Boulevard, the entrance to a large State Park invites visitors to Ragged Neck. Here again the State of New Hampshire has arranged a picnic area where the sea breeze tempers the noonday sunshine while a picnic lunch is enjoyed and sea gulls come closer and closer to stand upon one leg, hoping for a share of the contents of the lunch basket. A picnic repast on Ragged Neck possesses an unforgettable flavor when it includes fresh lobster, cracked on the spot, and fried clams dipped in butter.

A courteous clerk will welcome the visitors and clean facilities are ready within the State’s buildings.

Rye Harbor with Little Neck and Ragged Neck State Park

Back in history to 1792, the inhabitants of Rye voted at a town meeting to appoint five citizens “to dig out where they think proper” to enlarge the inlet, which was then the widened mouth of the stream that flowed from the marsh. That this was a popular enterprise was proved when forty-six men worked from one to six days each and five of them brought a yoke of oxen. One man worked fifteen days and also furnished ten gallons of rum.

The harbor was dredged to allow ships of forty ton burden to safely anchor. This increased the fisheries in the summer. In winter the schooners plied in the coasting trade, even shipping cargoes from the Isles of Shoals to Boston.

In recompense to the men who excavated the harbor, an alder swamp and Thatch Pond were drained in the marsh, and each man received a tract of the salt marsh according to his rights.

Throughout the War of 1812 fear spread that the British Navy might interfere with the coasting trade, especially after a blockade was declared by England. Warships of the enemy scouted around the harbor at Portsmouth. The forts were too well equipped for defense to fear attack by the enemy.

The Town of Rye prepared for invasion. Two cannon were placed on the green by the meeting house at Rye Center. A “good supply of ammunition was stored under the roof.” General Thomas Goss organized a company and “supplied each man with a good fire arm and a half pound of powder and balls.”

Battle At Rye Harbor

Terror struck on May 29, 1814 when two British warships anchored off the Rye shore. The bell at the meeting house rang the alarm. Families packed valuables for flight inland. One woman took her children and her best feather bed in her wagon and fled in the night, collided with a carriage without too much damage, and both drivers went on their way without recognizing one another, so hurried was their action.

The following day a schooner from Portsmouth sailed by the British ships. A barge gave chase. General Goss had placed his men behind stone walls on either side of the harbor. The schooner entered the harbor, the barge closely following. A man at the Neck hailed the barge and was answered by a volley of shots. At command of General Goss, his men opened fire furiously shooting their entire supply of ammunition.

The coxswain of the barge was seen to fall and several others were wounded, before the barge withdrew to the warships. The reef where the British anchored has since been called Gunboat Shoals.

Meanwhile two boys were sent to order that one cannon be brought from the meeting house. This was attached to horses which started with such speed down “Breakneck Hill” that the bottom of the ammunition case fell out, causing some delay. After a second start one of the horses balked, and the cannon did not arrive in time to join in the fight.

A messenger was sent to Portsmouth for a company which started for Rye but were met on the road and told that the battle was over. Hundreds of people arrived to stand out of range of the guns to watch the events. Even the two boys who were sent for the cannon rushed back to the harbor and stood near the fish houses where they heard balls fly over their heads.

The warships weighed anchor to sail away and the schooner in the darkness of that night returned to Portsmouth.

About 1960 Rye Harbor was again enlarged, breakwaters were constructed, and the channel was dredged to permit motor boats to enter. During the summer scores of boats, large and small, drop anchor for the night.

Gunboat Shoals now is protected by a bell that can be heard on shore when the waves toss over the reefs — a reminder to old timers of the only naval fight on the coast of New Hampshire.

One of the pleasures at the shore is chatting with so called “natives” who recall incidents of earlier days. Stopping to inquire about the location of Gunboat Shoals, a man past middle age proved to be a rich source of local information. Breakfast Hill on the horizon to the north and Brackett’s Lane were mentioned, scenes of two encounters with Indians.

Glacial markings on Foss Beach ledges

Then came a reminder of a prosperous business of eighty years ago; “My wife goes out to find that moss and cooks a pudding occasionally.” Old cookbooks named the pudding “blanc-mange.” While sailing along the Rye coast in 1883 W. H. Burke of Ipswich, Massachusetts noticed quantities of sea moss growing on the submerged rocks.

Experienced “mossers” gathered this plant off the somewhat dangerous ledges. To bleach, dry and package this product was an exacting process. From June to September the little green boats of the mossers were scattered over the waters around Rye Harbor until about 1910. Today housewives use gelatine instead of the product of the sea.

Foss Beach and Ledges

From Ragged Neck the shore is a mixture of sand and rocky shingle called Foss Beach, perpetuating the name of an original pioneer family. Then Foss Ledges, scarred by the glaciers, is a favorite spot to stop the car to watch the breaking waves in summer but even oftener in the fall and winter to enjoy the surf.

Exploring will be changed if the Washington Road is followed that turns inland at the Ledges. Originally this was the Indian Trail that ends at Breakfast Hill, first passing through the beautiful village of Rye Center. A network of highways runs northward from the old trail, among them Brackett’s Lane or Road to Little Harbor where a most interesting old Seavey House has stood since 1755.

The old chimney opens upon six fireplaces. In the kitchen the brick oven can be heated by the old method, and beans, brown bread, and turkeys will cook with the old-time flavor. Two brick closets connect with the chimney, one to be used for the family silver, the other for liquors.

In the transom over the front doorway are the bull’s-eye panes of glass, now almost priceless heirlooms. The house has remained in the Seavey family these two centuries with many family tales in its history. When Martha married a son of the Langdon Family of Sagamore Creek she was given, as a wedding present by her parents, a black slave and a black cow. Her sliver spoons are cherished by another intermarriage with the Parsons family, the name of the second ordained minister of the Rye church.

Wallis Sands

The last beach of the eight miles of Rye Shore is also an ancient family name, Wallis Sands. The State Park here has been recently provided with modern facilities and a protecting seawall. Threading to the sea is Pass River; its earlier name was Doctor’s Creek because Dr. Joseph Parsons built extensive salt works and a grist mill near Concord Point.

Facilities at Wallis Sands State Park

Beyond Wallis Sands the shore becomes low cliffs and the Boulevard turns inland to pass through the ancient Wallis Farm later purchased by descendants of Rev. Samuel Parsons, ordained in Rye in 1736. In the fields of legislation, education and the professions this family has brought many honors to the Town of Rye.

Langdon Parsons wrote and published the History of Rye in 1903 and Prof. James Parsons of the University of Pennsylvania presented to the State whatever of his land was required to construct the Ocean Boulevard.

During World War I the United States Government established military installations along this rocky coast, erected a high wire fence along the Boulevard, and only with permission of officials is anyone allowed to pass behind this barrier.

Odiorne’s Point

A slight elevation within the Reservation is the site of Pannaway, the first permanent settlement in New Hampshire in 1623. This site may be easily discovered directly opposite the beautiful dahlia gardens close to the wire fence. Nearby is the large homestead that is the third house, built about 1660, by the Odiorne Family who gave their name to the Point.

Among the many fishermen who were exploring the toast about 1620 was David Thompson who is described in the book of 1637, The New England Canaan as a “Scottish gentleman, a scholar, traveller and a man of good judgment.” He was searching for a harbor that might be easily protected from hostile Indians.

In 1623 Mr. Thompson received a patent from the Grand Council of Plymouth, England to “Find some fitt place to settle and build some houses for Habitations.” Accompanied by at least ten men, he sailed in mid-winter in the ship Jonathan of Plymouth and arrived in the spring at his chosen site which he named Little Harbor.

Near a bubbling spring a house of native shale and blue clay was built of sufficient size to accommodate the entire colony, probably including a Mrs. Thompson and several more women.

The news traveled somehow that Pannaway was inhabited. In June. Miles Standish arrived with other Pilgrims to request that he might purchase food for the hungry Pilgrims. David Thompson divided his supplies to save the Plymouth Colony from starvation.

Of considerable importance was the birth of the first English baby in New Hampshire to the Thompson Family, who was named John Thompson. His father fulfilled his contract with the Plymouth Company in England and departed to become the owner of an island that was given to him by the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

The Odiorne Family was granted forty-two acres on Great Island soon after arriving with the emigrants from England in 1631. Later John Odiorne received one hundred fifty-two acres that are the farm on the Point that bears the name of the family who retained the property until recent years.

Explorers should visit the first cemetery of the white men in New Hampshire which occupies a space perhaps a hundred feet by sixty feet in the rear of the homestead that is the third that was erected by the Odiorne Family — a two-story, white house beside the Boulevard, surrounded by green lawns and shade trees.

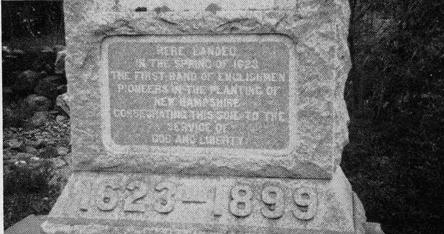

The western side of the cemetery has been used for a burial place for members of the Odiorne Family, but two-thirds of the space is filled with about forty graves indicated by small natural head and foot stones. No record tells who rests beneath this sod. A granite monument was placed in 1899 by the Colonial Dames of New Hampshire to mark the first settlement in New Hampshire, “Consecrating this soil to the service of God and Liberty.”

Ralph Brown, the present owner, and his brother, Kenneth, welcome visitors to this sacred God’s Acre which they keep with patriotic devotion. Their gardens are magnificent with summer flowers of many varieties, but the specialty is dahlias of every type, color and size.

Isles of Shoals

Unless a trip to the Isles of Shoals is included, the Seacoast has not been completely explored. Choose the time when the weatherman promises at least two days of fair sunshine, when the crescent moon is approaching the full, and plan to stay at the Isles for a night. Not too early in the morning, sit upon the cliffs to the east and watch the sun pierce the fog in rainbow colors to enjoy an experience of a lifetime.

To take passage upon The Viking, the way is along Market Street in Portsmouth past the original Strawbery Banke where the first landing is said to have discovered the ripe strawberries that refreshed the pioneers after three months on the voyage. Also, the weathered store-houses are ancient.

Odiorne Monument

The sail of seven miles down the harbor permits views of the Portsmouth Navy Yard in Kittery, Maine, and the lighthouses and fortifications at Fort William and Mary. Another seven miles is a sea voyage with backyard looks at the entire coast and forward to watch the Isles rise above the waves.

Questions may be asked. Why the name Shoals? How far from the mainland? Do people live there the entire year? Here are the answers. Three hundred years ago Shoals meant fishing grounds, and the first name was Shoal Isles, now reversed to Isles of Shoals. The nearest line to the shore is at Straw’s Point, six and one-half miles. Yes, hardy lighthouse keepers and a few other people live on the Isles throughout the year.

The New Hampshire Planning and Development Commission published an excellent geological book that was written by Mrs. Katherine Bowler-Billings about the origin of the Isles. They supposedly have a rectangular base of rock that is three miles in length and one and a half miles in width. Perhaps some three or four million years in the past, a mountain was pushed from the interior of the earth that has been worn by several ice ages to its present level, its summit sheared off and lying under the sea. Nine hard cores did not wear away but became the Nine Isles that are surrounded by nine dangerous reefs which are submerged except at low tide.

Gradually, independent fishermen settled permanently on the Isles without grant of any government. They framed their own rules and established a trading post on Lunging Island.

The King gave patents to New Hampshire and Maine to John Mason and Sir Ferdinando de Gorges who drew a dividing line through the mouth of the Piscataqua River in 1635. This placed five of the islands in Maine and four in New Hampshire and so they remain to the present day.

Then the fishermen were taxed five pounds for every thirty tons of their shipping. Since the Islanders acknowledged no government, they refused to pay and they never did. But they did relax one of their rules which had forbidden a woman to live on the Isles.

Two wives of fishermen arrived in 1635 who stayed against the wishes of other men. After the English Court claimed possession in 1650 women were declared welcome if “they did not sell wine, beare or liquors.”

Tales about pirates should be included in this story. Although Shoalers were suspected of piracy, history denies this. However, a few may have shut their eyes to suspected cases. The King’s Navy offered rewards to Shoalers to spy upon pirate ships. Twenty sea rovers were known to cruise along the coast of Maine.

It is believed that pirate ships landed untold treasure to hide on the Islands. Some $100,000 has been discovered. In 1960 Life Magazine stated that $275,00 was hidden on Star Island and only half has been recovered.

During the Revolution, Islanders were commanded to move to the mainland. One widow Pusley had two cows which she fed with hay that she managed to cut with a knife. When English soldiers took possession of the Island they bought her cows, then ate them for food, to her tearful distress. She moved to the mainland but returned to die later on her beloved Isle at the age of ninety years.

After 1832 Thomas H. Laighton, son of a wealthy family in Portsmouth, became the influential business man at the Shoals. He was keeper of White Island Lighthouse and lived there with his wife, daughter, Celia and sons, Oscar and Cedric Levi L. Thaxter of Newton, Massachusetts joined in erecting the Appledore Hotel in 1848 which was the favorite vacation spot for musicians, educators and authors until it burned in 1914.

Celia married Levi Thaxter in 1850. She is remembered for her poems and her Island Garden where she is buried.

Meanwhile at Star Island a group of Unitarians opened a conference at the Oceanic Hotel. An association was organized in 1896 and years later the Congregationalists joined them. Today the summer gatherings are crowded.

The United States Government constructed a breakwater between Smuttynose and Cedar Islands and another to Star Island, providing a safe harbor. The steamer Viking sails daily from Portsmouth.

Today all of the islands are sites for summer homes where the isolation from the mainland offers quiet relaxation unless the forces of Nature occasionally disturb the tranquillity.

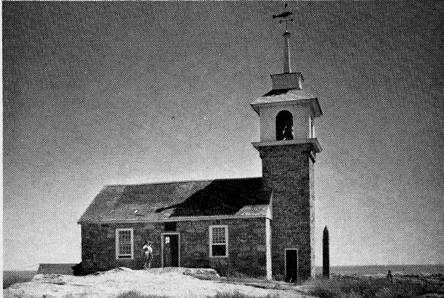

Stone chapel on Star Island, Isles, of Shoals, 1800

The small stone chapel once showed candles in its steeple for guides to the harbor. Since 1820 White Island lighthouse has sent the rays of its beacon from a tower of stone ninety feet in height. A new tower with walls two feet thick was erected in 1865 which flashes yellow gleams at fixed intervals while a powerful fog horn warns ships away from the dangerous reefs.

Vespers in the chapel grant inspirational memories. A candle lighted lantern is furnished to everyone in the office of the Oceanic Hotel who desires to attend the service. Single file in silence the group climbs the narrow pathway to the chapel. Each enters and hangs his lantern upon a bracket along the four walls until soft candle light fills the room. Hymns are sung, a selection from the Bible is read, a brief meditation may be spoken, and evening prayer expressed. Then again in silence each worshipper lifts his lantern and descends the pathway to the hotel while the splashing of the waves against the cliffs calls to rest.

Such is the history of the Shoal Islands through three hundred years, off the coast of New Hampshire.

After this excursion away from the actual seashore, the trail is resumed from Odiorne’s Point along the Shore Boulevard to Little Harbor road where the circle to Great Island passes through Newcastle and into Portsmouth by Newcastle Street and Marcy Street.

Newcastle on Great Island

Beyond Odiorne’s Point, Sagamore Creek is crossed by a rumbling bridge, and the Little Harbor Road turns to the right. Not very far along this road the sign will be discovered for the Benning Wentworth Mansion on the left. The lane winds to the bank of the river where a large anchor rests on the lawn.

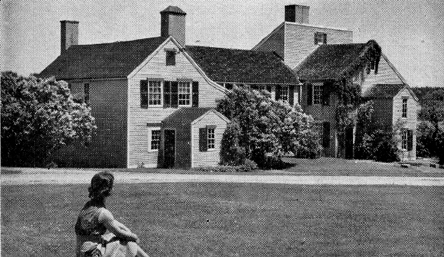

Gov. Benning Wentworth Mansion, 1760

This rambling house with many different slants to its roofs was erected about 1740. It was then repaired and many rooms were added by Governor Benning Wentworth who was a son of John Wentworth, lieutenant Governor of the Province and a wealthy shipbuilder.

There were fifty-two rooms in 1750, and the cellar could stable thirty horses if needed for war. The Council Chamber is spacious and its carved fireplace is said to have required the skill of an artist in white pine at least a year to complete.

On his sixtieth birthday, the Governor married the young and attractive Martha Hilton, who had been only a maid in his household, and the marriage proved a happy one during the remaining six years of his life.

After the death of the Governor the mansion became the property of Colonel Michael Wentworth of England. He married the widow Martha and resided in the house the rest of his life.

Today the house is vacant, after being presented to the State by the Coolidge Family. Around the lawns are beautiful lilac shrubs that are scions of the first lilac plants that were brought to New Hampshire. A commission appointed by the State is renovating the house and furnishings are planned in keeping with the history of this mansion.

Great Island partially fills the mouth of the Piscataqua River with its ledges leaving a wide harbor to the north and Little Harbor to the south. Bridges from the mainland almost conceal the fact that Little Harbor road crosses the water to the Island.

In the very early days these parts of the river seemed to protect Great Island from sudden attacks by Indians to the extent that about 1660 many of the families left Portsmouth for safety and erected their Colonial homes in a compact village on Great Island, depending upon ferries to the island.

The first fort was on the point near the wider harbor, its four great guns offering protection if pirates ventured up the river. In 1693 a petition was offered to the Governor for a township. This was granted with the name Newcastle. After leaving the Benning Wentworth Mansion, views of the ocean in the distance stretch to the south, and the bridge to the Island is crossed. Here the popular hotel, Wentworth-by-the-Sea, dominates the landscape. From May to November the hotel is crowded with meetings of many societies and organizations of every title and aim. Between these busy groups, summer guests fill the four stories to overflowing. The house gained international fame in 1905 when Russo-Japanese delegations selected this isolated spot for their deliberations for signing the Peace of Portsmouth, with President Theodore Roosevelt acting as mediator.

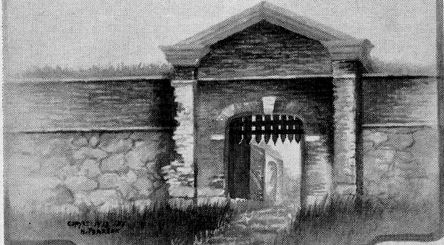

Portcullis of Fort William & Mary, 1774

Soon the village of Newcastle charms a visitor. One should walk around through its narrow streets to appreciate the early Colonial architecture, and stand for a moment by the quaint meetinghouse where a person of great respect in the ancient village had the honor to be buried at the corner of the building, although his name is forgotten.

Continuing on the circular drive, the contrast of modern ranch type houses with the Colonial is striking, yet it is pleasing to find them among the ledges in unexpected places.

Fort William and Mary

Continuing along this road, the gateway to old Fort William and Mary is on the right. Here are ruins of ancient walls and defenses for the present. In 1631 John Mason sent cannon and ammunition for a fort at the mouth of the harbor, because dangerous pirates sailed along the coast. In 1666 the fort was enlarged with every person over sixteen years of age expected to work a week between June and October. The name William and Mary was assigned at this time.

After its capture by patriots in 1774, the name was changed to Fort Constitution. Later, before the War of 1812, stronger fortifications prevented the English warships from trying to enter the harbor.

In the time of the Civil War new fortifications were not completed but these were modernized in the Spanish War. During World War I extensive defenses were installed at the fort and along the coast.

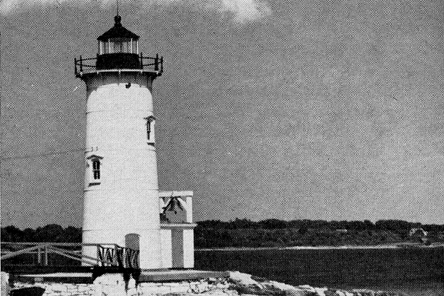

Visitors may wander around certain sections of the old fortifications and visit Old Fort Point lighthouse. Long ago the only beacon for ships was a lantern placed at the top of a flag pole by order of the legislature. Before 1784 a wooden tower with a light was sending its rays over the entrance to the port. In 1804 a new wooden light was erected, eighty feet in height. The present cast iron tower was built in 1872 with a light installed that may be seen a distance of ten miles out at sea. A residence for the keeper was constructed at the same time, much nearer to the shore than when the first tower was erected, but this is only one of the beacons in the harbor.

Newcastle Street follows the bank of the Piscataqua River to Portsmouth. One small island just off the shore has unusual records, named Pest Island, as it truly was.

Smallpox was dreaded by all people of very walk of life. It is stated that President George Washington carried the marks of his attack to his grave. The discovery was evidently true that, if a person were in good health when exposed to the illness, his case would be mild and with certain treatment no disfigurement to the face would result. Pest Island was the spot that was set apart for people to stay while having the pox.

Fort Point Lighthouse, 1877

After crossing the bridge into Portsmouth, if Water Street at the bank of the river is followed, the cemetery, Point of Graves, is passed. Here is the grave of Tobias Lear and other members of his family. The headstones are ancient yet carefully preserved. The following quotation reveals much: “On March 2, 1671, Captain John Pickering agreed ‘that the towne shall have full libertie without any molestation to inclose about half an acre on the neck of land upon which he now liveth, where the people have been wont to be buried, which land shall be impropriated forever for the use of a burying place, only the said Pickering and his heirs forever, shall have libertie to feed the same with neat cattle.'”

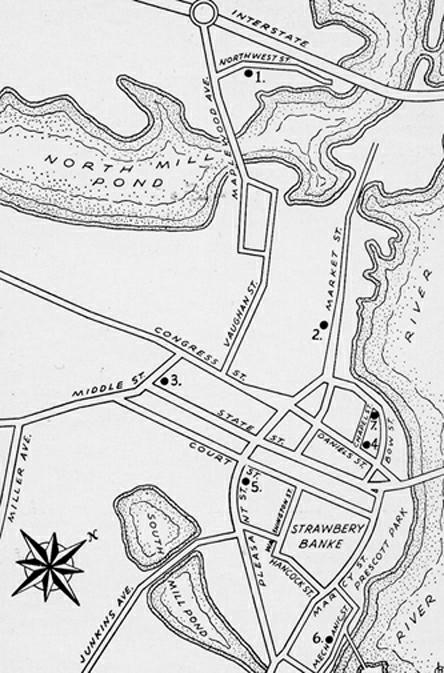

Strawbery Banke

On a June day in 1631 the ship Pied Cow sailed up the forested banks of the Piscataqua River to anchor beside a steep bank that was red with wild strawberries. After tossing at least ten weeks within the hull of this small ship, imagination fails to grasp the joy of the 80 voyagers when they tasted the berries. Until those pioneers were no longer alive, their settlement was Strawbery Banke or The Banke.

Within the cargo of the Pied Cow was the frame of the Great House, ready to be raised by Humphrey Chadburne, an engineer whom John Mason commissioned to build houses and set up saw mills. There is a record that eighteen saw mills were running before Chadburne erected his own home across the river in Berwick, Maine. A site for the Great House was chosen near the bank of the river, east of State Street. This was shelter for the eighty pioneers until separate homes were erected near an inlet that was named Puddle Dock.

Strawbery Banke, Inc.

The above is the name of ten acres today, selected at about the site of the Great House, that are reserved to preserve over thirty buildings which date between the mid-seventeenth and the nineteenth centuries.

To the first President of Strawbery Banke, Inc., Miss Dorothy Vaughan, due honor is awarded. Realizing that many historic landmarks were in danger of destruction because of Urban Renewal, in 1957 Miss Vaughan aroused many responsible citizens to action. Strawbery Banke, Inc., retaining the old spelling, became a legal organization with Miss Vaughan elected its President. Contributions from citizens and a Federal grant have made a beginning for a remarkable museum of Colonial Portsmouth that is visited by hundreds during the summer months.

The architects who restored Williamsburg, Virginia, Perry, Dean, Hepburn and Stewart, have planned the arrangement of streets and sites for buildings within these ten acres. Twenty-seven houses have been acquired to date.

Gov. Goodwin Mansion (1811) restored and furnished, at Strawbery Banke

Three of the homes have been fully restored and furnished: the Captain John Clark House, 1750; the Chase House, 1762: and the Governor Goodwin Mansion. 1811, which he purchased in 1832 after he retired from an active sea career.

Puddle Dock

The unearthing of Puddle Dock began on April 7, 1966 by the students in the Department of History at the University of New Hampshire. The old wharves were filled in 1889. The work of excavation is directed by Roland Wells Robbins, a professional archeologist of Lincoln, Mass. For the students who are participating in this experiment in historical site archeology, Mr. Robbins first conducts them on a tour of the site to explain his theory of how history is hidden in the soil.

A long section of the wharf was dug to reveal what appears to date from two periods. One side was built of squared timbers supported by piles, while the earlier side was constructed of logs. A chart of the dock, dated 1813, shows earlier cribbing.

On April 29, 1966 the spar of a ship was uncovered, also a large log at right angles to the length of the wharf. Various artifacts have been found, provisionally dated 1710. These include fragments of pottery, a clay pipe stem, and a piece of coral whose use is not understood yet; it is usually found in excavations around old wharves. When this project is completed, a line of willow trees will indicate the south bank of Puddle Dock.

The Daniel Webster House

On the corner of Washington and Hancock Streets the Daniel Webster House of 1786 is to be restored with contributions by school children of the State.

Stoodley’s Tavern

Another ambition for the near future is the restoration of the famous Stoodley’s Tavern (also spelled Studley’s) of 1765. Once the most fashionable tavern in Portsmouth, stages between Boston and Falmouth (Portland) stopped here. Rogers’ Rangers and the patriots of the Revolution gathered within its walls. The upper story, formerly used by the Masonic fraternities and for assembly dances, will be one arched hall lighted by dormer windows. Music for the dancers was once furnished (with sometimes a tambourine added) by a skilled violinist, Michael Wentworth, who married the widow of Governor Benning Wentworth.

After the death of Col. Stoodley, his daughter and her husband, Elijah Hall, a retired ship builder, occupied the tavern. Captain Hall shipped as a lieutenant with John Paul Jones on the Ranger. He was a member of the Governor’s Council and a naval officer when he died in 1835.

Exploring Famous Residences

The beginning of this exploring should be at the earliest structure now remaining in Portsmouth, the Jackson House of 1664. This is located on the Christian Shore, so named by a scornful, rough sailor, at Northwest Street. John Jackson, the builder was evidently an Englishman who remembered his home in the old country.

Because the forests in England had been depleted, wood was scarce for building material, and floors in the Saxon homes were the bare ground. The old expression “hoeing out” meant just this operation. Then fresh earth was pounded by wooden mallets to hardness and fragrant herbs were scattered.

The cold winters in New Hampshire demanded floors, yet the method of laying them was unknown to the average pioneer. At the Jackson House visitors will notice foot square timbers around the walls above the floors. It is believed that a stone foundation was constructed, then planks were laid upon this for the floor, and the heavy sills were placed over the planks to hold the floor in place.

The narrow stairway is difficult to climb for a broad shouldered person. The fireplace has an enormous chimney that drew the heat upward so that the oak stringer is hardly scorched. The salt-box roof almost touches the ground. The two wings are later additions.

The Jackson House, 1664

The house was willed to Robert Jackson, a son, together with 100 pounds. The Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities now preserves the house but requests a small fee for admission.

The Warner House

Next in importance of age and many other features is the brick mansion at the corner of Daniels and Chapel Streets, known as the Warner House. This is the oldest specimen of Georgian architecture in New England. It was erected in 1723 by a Scot, Captain Archibald MacPhradris. He was a ship builder who sent his vessels abroad, and the bricks are said to have come from Holland as ballast. Bills of lading prove that the furniture and silver were also imported from Holland.

The Warner House, 1716

The gambrel roof is not original. In the attic may be seen two peaked shingled roofs extending the length of the house now covered by the gambrel roof. Captain MacPhradris ascended the winding staircases to the Captain’s walk upon the roof to watch for a ship that was late in sailing up the harbor.

He discovered bog iron in the Lamprey River which he used for the latches and hinges in the house. Advertisements were sent to Scotland offering high wages to iron-mongers if they would emigrate to New Hampshire.

To the surprise of her friends, Susan Wentworth, daughter of the first Lieutenant Governor appointed by the King, married this Scot but he soon became a favorite of the elite of the town, and was a member of the King’s Council of the Colony.

Along the walls of the arched staircase are paintings of scenes of historical and Biblical subjects, found in 1850 when a bit of the four layers of wallpaper was torn. The elk’s horns are a gift by Indians to Captain Macphradris. The house takes its present name from John Warner who married the daughter, Mary MacPhradris.While living there, Mr. Warner allowed Benjamin Franklin to place a lightning rod on the west side of the house. The house was sold in 1931 to the Warner Association that opens its rooms in summer to visitors, for a small fee.

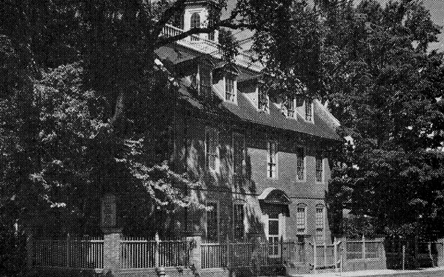

Portsmouth Historical Society

Portsmouth Historical Society

Next by date of 1730, at the corner of State and Middle Streets, is the gambreled roofed Lord House. This resembles the exterior of the Warner House except that the material is wood. Captain Purcell, a shipping merchant, erected this residence but died within a few years, and his widow maintained a boarding house in these panelled rooms. The staircase is an example of panels and carved balustrade. Both in the lower and the upper rooms the fireplaces have tiled or carved mantles and the furnishings are a collection that has been preserved by the Portsmouth Historical Society which owns the house.

In 1777 the distinguished guest was Captain John Paul Jones who was supervising the construction of the warship Ranger. Captain Jones was a handsome naval officer whom the young ladies of Portsmouth admired. The tale is true that these young women cut up their silk dresses to sew a stars and stripes flag to present to the Ranger, the white stripes made from a wedding dress. This flag was saluted by the French Admiral, first honor to the stars and stripes of the Colonies. Again in 1779 Captain Jones was in Portsmouth while the America, largest ship in the Navy, was built. The house was sold to John Langdon and then to Samuel Lord, a prominent banker who gave the house its present name, the Lord House.

The Tobias Lear House

The grandfather of the same name as the secretary of George Washington, Tobias Lear, III, erected this house on Hunkins street in 1740. His grandson was born in 1760, was graduated from Harvard College in 1783 and soon became private secretary to General Washington and tutor for his stepchildren. To President Washington he was so close for sixteen years that he knew confidential government business.

After the death of Washington, Tobias Lear was appointed to be consul in several embassies abroad and finally was accountant in the Treasury Department when he suddenly died in 1816.

The house has a hip-roof and in the attic the old slave quarters may be seen. The wallpaper in the west parlor is said to be the same as when President Washington and Col. Lear called upon Mrs. Lear in 1789. Secretary Lear married relatives of Mrs. Washington and the house remained in the Washington Family until about the time of the Civil War. Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt and other distinguished citizens contributed to an endowment to preserve the house for posterity.

The Thomas Bailey Aldrich House

On Court Street is the boyhood home of Thomas Bailey Aldrich who wrote the “Story of a Bad Boy.” Instead of using his own name he substituted the name of his Grandmother Nutter to shield the family from publicity.

Erected in the middle of the 18th century, the house is furnished with articles that are described in the famous book. The old garden remains in the rear, and at the side of the house is a fire-proof building that contains priceless treasures that belonged to the Aldrich Family. Time to visit this Memorial is well spent.

The Wentworth-Gardner House

The Wentworth-Gardner House, 1760

To visit the Wentworth-Gardner House which is reported to be “the most perfect specimen of Georgian architecture in this country,” one looks for Mechanic Street.

Mrs. Hunking Wentworth gave this house to her son Thomas for a wedding present. A bit of tradition tells that she distinguished this son, by the extraordinary gift, while his brother John was in England to represent the family’s shipping business and was receiving honors from royalty.

Here is a hipped-roofed, wooden mansion with its doorway ornamented with 15 panels and a “broken” pediment containing a gilded pineapple, a symbol of hospitality.

Unrivalled are the wood carvings throughout the rooms which employed three master carvers some fourteen months to complete. The central staircase is richly carved, the fireplace in the south drawing room has a festooned ornament, pilasters are fluted, and within the window casing in the upper hall is the carved likeness of Queen Caroline. Dutch tiles border the fireplaces, and the wallpaper has old English designs.

A linden tree flourished before the doorway, brought from England when the house was erected.

In 1792 the house came into the possession of Major William Gardner who was appointed commissary for the army in the Revolution. When the Treasury was practically depleted, his reputation for honesty was such that he obtained blankets by giving his personal note in payment.

The Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities is preserving the house today.

The Moffat-Ladd House

With the intention of surpassing the architecture of Mrs. Wentworth’s mansion, Col. John Moffat erected the first square, three-story house in New Hampshire on Market Street in 1763, which was also a wedding present for his son Samuel.

The entrance hall is a reproduction of the ancestral home of Col. Moffat in England. The staircase with carved balustrade, and the soffit with its beautiful oval are distinctive works of the carver’s art. Roses at the corners of the cornices, patterns on the fireplace, arched alcove in the dining room, and the wallpaper design of the Bay of Naples demand attention of visitors.

The mantle of the fireplace in the living room is claimed to have been carved by the famous Grinling Gibbons, an architect of 1666, in England.

The house became the property of General William Whipple, signer of the Declaration of Independence. Another owner presented it to his daughter, Mrs. Alexander Ladd, whose descendants sold the estate to the Colonial Dames of New Hampshire, who maintain it today.

The spacious garden with its central walk and grass steps was designed when the mansion was erected, and damask roses of that period still bloom there. Many of the flower-beds are still planted as in past years.

A captain’s walk crowns the hip-roof, and the shipping office of Col. Moffat beside Market Street contains the original desks and cabinets for records of the ships that once docked along the bank of the river.

Gov. John Langdon Memorial Mansion

Gov. John Langdon Memorial Mansion

John Langdon was born on a farm near Sagamore Creek. He attended Major Hale’s school, then entered the counting house of Daniel Rindge. At this period a young man could build a ship, fill the hold with a cargo of pipe staves and hoops for hogsheads, ship them to the West Indies, set up the hogsheads and fill them with rum or molasses, sail to England, sell this cargo and perhaps the ship, repeat this exploit many times and at the end of twenty years become a wealthy shipping merchant. This was exactly the career of Gov. John Langdon.

When the Revolution called for patriots, John Langdon responded with his time and fortune. On the evening of December 13, 1774, when Paul Revere rode to the door of John Langdon and delivered his message that the British were about to come to Portsmouth to carry away the ammunition from Fort William and Mary, he joined John Pickering and John Sullivan in immediate action.

Regardless of the warnings from Governor John Wentworth, the patriots rowed to the fort, over-powered the five guardians there, and captured 100 barrels of powder, later hidden at Durham, a part of it in the high pulpit of the meetinghouse. The following day, December 15, cannon and other arms and more powder were seized. Gradually this booty was transported to Boston to be used at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Before the Battle of Bennington, John Langdon pledged his wealth to support the patriot cause. He filled both state and national offices and finally in 1789 he had the honor of informing George Washington that he was elected to become the first President of the United States. Langdon administered the oath of office in his capacity as President of the United States Senate.

His Georgian mansion was erected in 1784, reported in neighborly legend to have been a present to his wife. It stands on Pleasant Street, has a hip-roof and a captain’s walk with high balustrade. Its doorway has been described by architects as the most beautiful in New Hampshire.

The interior has spacious drawing rooms and dining rooms. The furnishings are in keeping with the architecture which is elaborately hand carved. The china is choice in the dining room.

This mansion is preserved by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, and is open to visitors during the summer months.

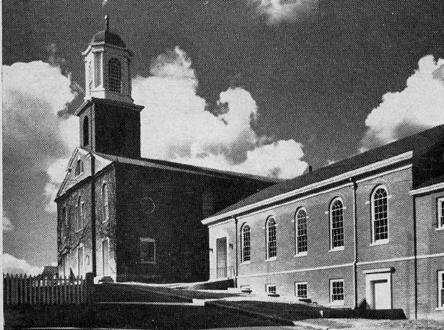

St. John’s Church

St. John’s Church, 1806

Although John Mason expected that his first settlers were loyal to the Church of England, they proved to be Puritans and banished the rector of the Episcopal Church. When the colony became a royal Province, many of the wealthy families conformed to the Episcopal denomination and Queen’s Chapel was erected in 1732 on a site above the bank of the river, now at Chapel Street. Queen Caroline presented the parish with a silver communion service, several prayer books, a Bible, and two elaborately carved chairs upholstered with red damask.

The Bible is one of four of the most valuable copies in the world today because the word vineyard was mis-printed vinegar in over thirty Bibles before the mistake was discovered. The Vinegar Bible lies open to this page today.

In 1806 Queen’s Chapel was destroyed in a fire that raged in the vicinity, but the Bible, the communion plate and one chair were rescued. Another chair was so perfectly copied that today it cannot be distinguished from the original. Immediately the present St. John’s Church was erected on the same site. The parish possesses more ecclesiastical relics of great value than any other in New Hampshire.

In addition to those already mentioned, there are priceless vestments that are worn by the rector at Easter Services, a font of porphyritic marble, and the oldest pipe organ in America which was first presented to King’s Chapel in Boston but was rejected as a “tooting tub.”

The pews and wineglass pulpit and other furnishings were imported from England, and the walls are hung with tablets that honor former members of the parish. The Governor’s pew was occupied by George Washington, Tobias Lear and Theodore Atkinson at the morning service in 1789 and the President attended the afternoon service in the North Church.

The bell was captured at Louisburg in 1745. After the fire in 1806 it was recast by Paul Revere, and again recast in 1896 with three hundred pounds of metal added.

A visit to this sanctuary is rewarding, and tracing the inscriptions on the tombs in the God’s Acre reviews many family names.

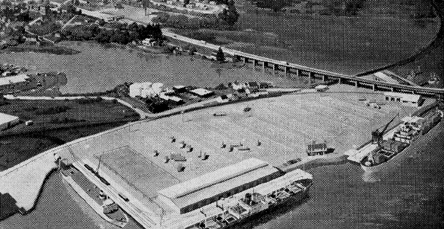

Portsmouth Navy Yard

The Portsmouth Navy Yard has been in operation since 1806 and is important to the economy of the city, although it is situated in Kittery, Maine. One hundred sixty years ago the United States Government purchased Fernald Island, then occupied by but one house, a farm and fish flakes.

Many wooden ships were launched here before and during the Civil War. The old frigate Constitution was stationed here before sailing to Boston to be equipped for its appearance in 1812.

After 1865 iron-clads were built. Then battleships lay alongside the wharf for overhauling. Submarines followed with many famous launchings. Now atomicpowered subs are the pride of the shipyard.

Pease Air Force Base

Portsmouth is celebrated not only underseas but in the air. The Pease Air Force Base was dedicated in September, 1957 and named in honor of Captain Harl Pease of Plymouth, New Hampshire who responded beyond the call of duty in the Pacific Islands in World War II. The Base is situated within the west section Marine Terminal of Portsmouth and extends into the adjacent Town of Newington. Thousands of officers and airmen are stationed here.

Runways and hangars for all types of planes, miles of streets, dormitories, administration buildings and many other facilities occupy several square miles. Married personnel reside outside the Base and the population of the city has increased by over 13,000 with housing at a premium.

United States Customs Services and Internal Revenue Offices are located in the city. Excellent educational opportunities are supported, also six banks, libraries, and churches. There are accommodations for tourists including the well known Rockingham Hotel built in 1830 with its Colonial dining room that was a part of the original residence of Woodbury Langdon, elder brother of John Langdon. The wood carving dates from 1783.

Driving along the streets offers a study of doorways and porticoes, designed by architects Bullfinch and McIntyre, and fences of several patterns.

The greatest potential for present and future growth lies with the harbor which is ice-free and the deepest and safest along the coast. Recently it was dredged so that the channel is cleared to accommodate ocean-going vessels of every tonnage.

Marine Terminal

In August of 1966 a State Marine Terminal was opened that is attracting firms that do business via water, such as the Simplex Wire Cable plant in Newington. The new State Pier and the large warehouse for storage for products that require cover are attracting shipping interests. The Port Authority is pursuing the idea that a foreign trade zone may be situated here that will permit goods to be brought into port free of duty on consignment, duty to be paid when goods are moved for sale.

On the State Seal the ship Raleigh proves that shipping was the chief industry in New Hampshire in the first one hundred and fifty years. Masts were cut and shipped for the King’s Navy and materials to build ships were taken to England until the King was convinced that the expense to build a ship where the timbers were growing was one third of the cost in England’s shipyards.

After carpenters were allowed to migrate to New Hampshire, shipyards flourished along the banks of the coastal rivers, giving employment to thousands, not only to the actual ship carpenters but in forestry, fishing and Colonial architecture.