By Rod Paul

New Hampshire Business Review , June 30 - July 13, 1989

Somehow, New Hampshire's court system seems to have bogged down over the prosecution of Robert McLaughlin, the former Hampton police officer accused of murdering his neighbor with a shotgun.

In the 13 months that have elapsed since Robert Cushing was gunned down in his own home and the 10 months since McLaughlin confessed to the killing, complicated legal issues have emerged provoking lawyers across the state to wonder what issues are left to confound the system's settling of the case.

Just a few weeks ago, without explanation to the accused McLaughlin, Justice Robert Temple, sitting in Rockingham County Superior Court, strode out of his chambers and accepted a surprise motion from McLaughlin's lawyers that they be allowed to remove themselves from the case.

This left McLaughlin, who recanted his confession in pre-trial maneuvers, without a lawyer to represent him, without understanding why his high-powered team of lawyers had gone.

"I can't figure it out, either," the imprisoned ex-lawman told one reporter in a telephone call from jail.

Since then, McLaughlin has been transferred "for security reasons" to the State Prison and refused legal help by New Hampshire's Public Defender's Office, which means the court will have to appoint an attorney to represent him — someone who will have to take more months to prepare McLaughlin's case from scratch.

Justice Temple was expected shortly to name a permanent defense lawyer for McLaughlin, but none he could name were expected to enjoy the aggressive reputation of his former defense team of Mark Sisti and Paul Twomey, whose departure remains puzzling to the public, as well as McLaughlin.

Those are just some of the procedural difficulties that have afflicted the case. Others include the successful challenge at one point by the Manchester Union Leader, which forced Temple to keep open a hearing that involved the trial of McLaughlin's wife and testimony that bore on her conviction as an accessory. The Manchester newspaper has since filed a motion to force the court to explain the reason behind the departure of McLaughlin's lawyers.

And then there is the complexity of McLaughlin's refutation of his own confession. And there is his convicted wife's claim — in love letters from prison to Robert McLaughlin — that she was the actual killer.

Temple has already acknowledged he will be unable to field a panel of jurors for another McLaughlin trial made up of members who have neither read nor heard of the details of the case.

"The problem with this case is that there are so many significant issues piling up and no explanation for what's happened," said one lawyer who practices in the Exeter courthouse and finds the McLaughlin case mind-boggling. "Has McLaughlin's legal team successfully put a doubt in the public mind? What if Robert McLaughlin is acquitted? Does that mean his wife, already sentenced to life as an accomplice, is tried again — this time as the murderer? Are his confessions real? The questions just go on and on."

The Mclaughlin case has become so convoluted that, before the trial was even to begin in June, legal maneuvers included the airing of issues as diverse as opposition to nuclear power, and even a widely disbelieved and immediately refuted report that three kilos of cocaine had been delivered to the home of the head of the state police, who lives across the street from the victim.

It is a case that New Hampshire's leading lawyers describe as bizarre. "There is nothing common about this case," said Stephen Tober, former president of the N.H. Bar Association.

McLaughlin has actually twice confessed to authorities that he killed his neighbor, whom he hated for years. At 48, McLaughlin had served 18 years on the Hampton force before he voluntarily turned himself in on Aug. 26, 1988, as the confessed killer.

In a departure from usual practice, authorities began their prosecution in the case nearly four months ago against McLaughlin's wife, Susan, 36, a short blonde woman, charging her as an accomplice to the murder. She was convicted in early May and sentenced to life in prison without parole. Susan McLaughlin then wrote her husband love letters from prison saying she killed Cushing. One letter said:

"I keep thinking that before your trial is up I should tell Bruce (her attorney, Bruce Kenna) that I'll admit to doing the shooting. I don't want to see you in prison, Babe. You don't deserve it. You're such a good person."

Another letter added, in part:

"Babe I pray they find you innocent. They've got to. You didn't kill Mr. Cushing, I did."

At the same time, her lawyer blocked her being summoned to testify in her husband's behalf at his trial, a move Robert McLaughlin's lawyers — the attorneys who have since removed themselves from the case — said prevented McLaughlin from being fairly judged. However, she has been deposed about the letters. The thrust of what she said about the letters is not public.

The murdered Cushing was a widely known former teacher and local real estate broker who had run into McLaughlin in past years, once intervening in an arrest by McLaughlin of a woman Cushing felt was too roughly handled by the officer.

This incident was one of the provocations that McLaughlin friends say produced bitterness in the policeman against Cushing. But there is more, much more, to the killing, say prosecutors and the former lawyers for McLaughlin.

The older Cushing, 63, father of seven children, a wounded World War II Marine Corps veteran, was prominent as an off-and-on critic of local government in the coastal community of 12,000, where he lived and died. He was known as sometimes acerbic in his discussions of local personalities and town selectmen decisions. He was also known as a respected resident who took an active interest in his community's well-being.

Robert Cushing Sr. died on the first night of June last year. He and his wife were watching a Boston Celtics basketball game about 10 p.m., when someone knocked twice at his door. He answered, opening the door. His wife described a bright flash and a thunderous shotgun blast with sufficient force to lift Cushing from the floor, hurling him several feet away from the entrance and killing him instantly. The murder weapon has never been found.

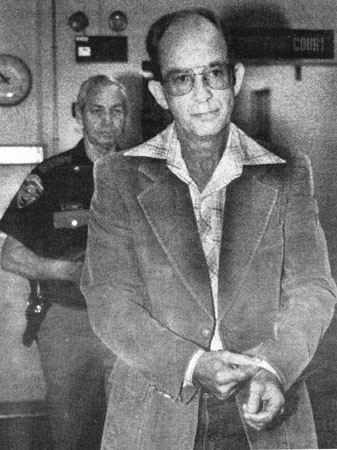

McLaughlin is a short, slight man who wears Western-style boots. He is described by his police colleagues as a "spit-and-polish" lawman on the job. But he is said by his first wife as having endured "dark moods" on occasion. A police officer pal of McLaughlin testified he twice tried to kill himself.

McLaughlin's wife was convicted of having stood watch during the murder. McLaughlin's own son, by a prior marriage, testified against Susan McLaughlin, claiming she told him she had been the lookout during the murder.

The murdered Cushing's son, Renny is a prominent antinuclear activist and former state representative. Young Cushing's views against Seabrook — by McLaughlin's own admission to a state trooper to whom McLaughlin confessed — so infuriated McLaughlin that he thought the family required some punishment.

Because McLaughlin bore a festering grudge against the Cushing family, partly stemming from the younger Cushing's notable and active work against the Seabrook plant, McLaughlin's attorney at the time, Sisti, screened some jurors ahead of the trial to determine their feelings for or against nuclear power. This is another peculiar twist in the case.

The Byzantine flavor of the case has even attracted the attention of the Fox television network, which has sent a camera crew to Hampton to film a segment for its program, "A Current Affair," one of the trailblazers in so-called tabloid television.