September 28, 1999

War, Growth Highlight Last 100 Years

By Steve Jusseaume, Staff Writer

The village, as it was called, was thriving, but in-town people seldom traveled east to the seashore. But that changed in the late 19th Century with the establishment of the Hampton Beach Improvement Company, construction of the Mile-Long Bridge across the harbor, the trolley company, and construction of a road from downtown to the ocean (now Winnacunnet Road) in 1892.

During the early part of the century, Hampton, like most other towns, felt the pain of war. More than 50 men and two women from Hampton served in World War I.

Soldiers from the town fought in the French battles of Chateau-Thierry and St. Michiel, and in the drive known as the Meuse-Argonne Drive, a critical battle between the Argonne Forest and the Meuse River. Hampton men also served on the transports Mongolia, Mount Vernon and Henderson. Others saw duty in the North Sea. After the war, in the fall of 1919, a dinner was served in honor of Hampton's soldiers at the Congregational Church, and 130 soldiers were present. Addresses were given at the Town Hall, followed by a dance and band concerti in the evening. Eleven of Hampton's 20 living Civil War veterans also attended the ceremonies.

Two years after Hampton celebrated its 300th birthday in 1938, a young American aviator named Raoul J. Bergoin became lost in the fog over the coast. He circled the town and beach, but eventually hit high-tension wires. The plane later crashed in the marsh, killing Bergoin.

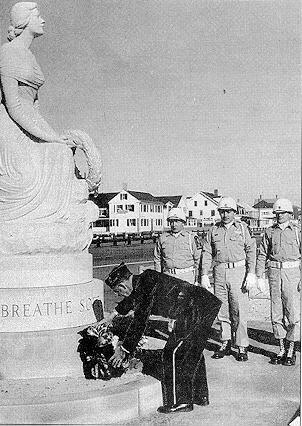

kind in the country, was unveiled in May 1957

on Hampton Beach. The memorial pays tribute to

those lost at sea. Above, a wreath is placed on

the memorial during the dedication.

[Courtesy photo/Tuck Museum]

In late 1942, the Seacoast was blacked out. Cars were limited to shining only their dimmer lights, black tape was used to cover headlights, and shades in beachfront homes ensured that no lights shone out to sea. In Hampton, more than 2,200 ration cards were issued by the end of May 1942, and more than 400 local residents attended a "Dinner for Democracy" on June 4 at the high school.

Ironically, the beach enjoyed record crowds during WWII, since any long distance travel was discouraged and New Englanders settled on Hampton Beach as a destination. Local historian Peter Randall wrote that more than $65,000 worth of Victory Bonds were sold in one three-hour period during the last day of a week-long celebration called "Victory Week" at Hampton Beach. War bond drives continued through 1943, 1944 and into 1945.

Finally, on Aug. 16, 1945, the local newspaper proclaimed,"Unrestrained Joy and Reverence Mark End of Second World Conflict. Joyful Celebrations Mark Long Awaited Jap Surrender."

Of the more than 300 Hampton men who served in WWII, 10 were killed.

On Armistice Day, 1946, Hampton dedicated its WWII Honor Roll.

Changes At Hampton Beach

[Courtesy photo]

Development of the beach, both north and south of Boars Read, increased as the 19th Century advanced Then, two years before Hampton Union was born, in 1897, the town embarked on a project that would change the face of Hampton Beach. At the April 1897 Town Meeting, the voters approved a 99-year lease of the town-owned sand dunes south of Boar's Head to the fledgling Hampton Beach Improvement Company (HBIC). Selectmen decided that a $500/year annual payment to the town by the HBIC would be appropriate. Wallace D. Lovell, an entrepreneur who built hundreds of miles of streetcar lines throughout eastern Massachusetts, in turn agreed to sublease the site of the future Casino from the HBIC for the sum of $500, the same sum that the HBIC agreed to pay the town.

The HBIC built roads, developed land, leased parcels out to developers, and built the beach south of Boar’s Head from sand dunes to a lively, and thriving, business, residential and tourist center.

By the 1980s, however, the HBIC lost its focus on development and when the lease finally ran out In April 1997, there was no consideration that it be renewed.

In the past several years, parcels of land east and west along Ashworth Avenue have been privatized, and the beach itself is in a position of possible dramatic change, as the town is currently considering changing zoning south of Boar’s Head to allow a different kind of development in the area.

Population Growth

a visit to the Hampton coast in 1912.

[Courtesy photo]

While in 1800, the population stood at 875, by the turn of the century, Hampton had 1,209 people living within its borders.

Historian Peter Randall attributes the fluctuations in population to various factors including the Industrial Revolution, which lured many residents to the larger cities, to the Civil War and to the westward migration after the 1860s.

During the early part of the 1900s, the population increased slowly. Hampton’s population in 1930 was 1,507, and in 1940 was 2,137. Then, after World War II, the population exploded. In 19~0 the population of the town was 5,379, and It grew to 8,011 In 1970. The growth rate of the town since has been above 10 percent per year.

Extensions of streets outward from the village in the early 1900s allowed for more houses to be built. What is now Dearborn Avenue was extended north from High Street in the late 1920s, and 10 years later Towle Avenue was extended south from High Street. In 1938, Moulton Road connected Winnacunnet Road with High Street. New roads meant new house lots.

After World War II, GI loans made it possible for young residents returning home from the war to buy new homes, and one developer who took advantage of the opportunity was J. Walter Hollis, who began building homes in earnest. In 1948, 75 new homes were under construction, including projects west of Locke Road, at Belmont Circle and Hackett Lane. In the 1950s, the building boom continued along Mace, Norton, Locke, and Moulton roads. In 1952, prefabricated houses In a 20-lot development were for sale along Leavitt Road.

(Published sources: History of Hampton, NH 1638-1892. Joseph Dow. 1894; Hampton: A Century of Town and Beach 1888-1988. Peter Randall. 1989; New Hampshire Town Names. Elmer Munson Hunt. 1970; The Hampton Union and its prior incantations. 1901-1999.)