By Paul C. Snyder

Correspondent for Foster's Daily Democrat

Reprinted with permission from the November 14, 1998 issue

HAMPTON - For more than 200 years, the tides and sand off Plaice Cove kept the secrets of the shipwreck of the mast ship St. George.

On Nov. 30, 1764, the St. George was plying the waves off the Hampton coastline, the cargo loaded with grinding stones, tools and other trade goods needed by colonists living in sparsely settled New England communities. As far as is known from archival records, the ship was not weathering a storm or dealing with heavy seas on that fall day. It should have survived her trip near the New Hampshire coast.

But the weary old ship ran up on the rocks and smashed, all because her Capt. William Branscomb didn't know the local coastal area and didn't have accurate charts that would have warned him away, according to "The History of the Town of Hampton." The St. George, similar in rigging and size to the Australian HM Bark Endeavour, a recent visitor to Portsmouth, had already seen long years of service and was nearing the scrap heap. Due to her deteriorating condition, the ship broke up rapidly after all hands safely made shore.

A colonel of the local militia, a gentleman by the name of Jonathan Moulton, was placed in charge of salvaging her cargo. Since the locals were not thrilled with the policies of the King and since record keeping was sparse, even nonexistent, they simply "helped" themselves to whatever they could lug away. After running his ship ashore, Branscomb settled in Hampton and became the third husband of Prudence Page (nicknamed "Old Pru").

Time, tides and shifting sands took their toll on the battered remains of the St. George.

The ship had its place in history. Since the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 by Sir Frances Drake, England's commercial and political influence were expanding throughout the world. To maintain that momentum, England needed lumber and tall, strong trees with which to make ship masts for its growing fleet of commercial and military vessels.

Through the King's "Broad Arrow Policy," mast agents for London ship builders were sent to North America to mark the tallest and sturdiest white pines with the Crown's mark of the Broad Arrow - three lines or cuts coming together in the shape of an arrow point. The marked trees were felled, transported to a mast dock at various ports dotting the Seacoast and loaded through "stern ports" in the mast ships, such as the St. George, for transport to England.

These mast ships were the greyhounds of their day and they plied the New England seacoast in the pre-Revolutionary War days loading and transporting the tallest and sturdiest white pines from the northern forests. It was an industry that flourished for 90 years up until the beginning of the Revolution.

But the St. George shipwreck was forgotten until the summer of 1962, when two teen-age Massachusetts skin divers diving near Hampton's old Coast Guard station made what some consider the find of a lifetime.

off Plaice Cove at North Beach

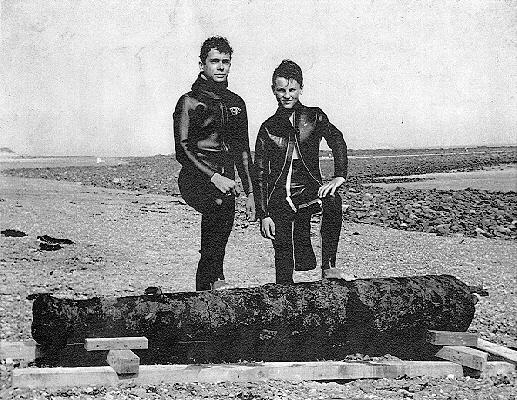

Walter "Skip" Hird Jr., of Methuen, and David Conrad, of Lawrence, were both 15 years old that summer. Hird's folks had a summer cottage near where the old fishing shacks stood, so Hird and Conrad would often head to Plaice Cove to dive. During a late June dive, the boys made a historic discovery.

"I was swimming along the bottom," Hird remembered recently, "and I bumped into this cannon. "It was the first time that I dove in the area since the winter storms, which had changed the beach configuration. Where once there were rocks, there was now sand and the cannon was kind of resting and pointing out of the water towards the Coast Guard station," he recalled.

"The way it was pointed, it looked as if you fired the cannon it would have hit the Coast Guard station." Its barrel weighed about 2,000 pounds and measured 8 feet long. With the help of an uncle who had a barge, the boys managed to inch the cannon onto the beach and move it next to their family's cottage. The teen-age boys kept the their discovery of the cannon secret from their families for nearly a month.

But you can only hide a cannon in plain sight for so long. A few of the locals started asking the boys about the cannon, then told them some of the stories about the St. George. That's when Hird and Conrad realized what they had. So did a museum in Washington, D.C. After hearing rumors about a cannon discovered from the St. George shipwreck, representatives from the Truxton Decatur Museum came up to Hampton to investigate. They confirmed that the boys had found something special.

The two divers were honored at a ceremony conducted at Fort Warren in Boston when author Edward Rowe Snow, a prominent New England historian, awarded them with the Order of the Purple Lanyard of the Cannon Hunters of America. No one is allowed to belong to the Cannoneers unless they have found cannons or cannon balls as amateur hunters. The cannon, worn smooth after being submerged in ocean water for almost 200 years, now resides in the Truxton Decatur Museum in Washington, D.C.

Over the years, Hird found other relics submerged a few hundred feet from the old station - cannon balls, a deck cannon and scuppers that were traced and identified as likely belonging to the wreck of the St. George. He said he offered them to the Tuck Museum in Hampton, but said museum officials weren't interested.

So, Hird keeps the relics in his Methuen home. "I keep hoping someone from the Tuck Museum will call me. I'll be glad to give them to him," he said.

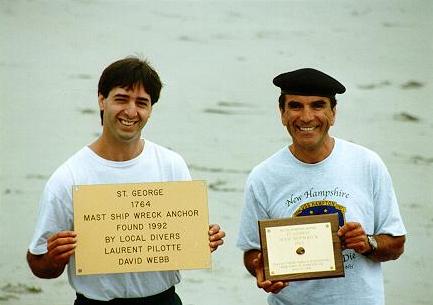

The next major discovery of the St. George wouldn't come until 1992 - 30 years to the month of Hird and Conrad's find. Larry Pilotte, an accomplished contract Ocean Dive Master, was diving in the Plaice Cove area when he and fellow diver David Webb found what Pilotte called "this most beautiful anchor" lying in about 12 feet of water about 150 feet from the site of the old Coast Guard station in Hampton.

Although Pilotte had gone on dives in the area for a dozen or so years, he had never spotted the anchor before. He believed that currents from a recent nor'easter had shifted the sand enough to reveal this relic.

The anchor was made of layered iron, with the stock made of a different metal, Pilotte said - with the rope "still wrapped around the anchor." But the anchor was firmly bonded to the rock it was lying against; only careful, tedious chiseling would free it. Researching the origin of the anchor eventually took Pilotte from Hampton's Lane Memorial Library to the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England, and on to the Dockside Museum in Portsmouth, England. His findings left little doubt that the anchor was from the St. George.

Pilotte, after several years of trying to lay a plaque where the anchor rests, managed to organize a ceremony that also coincided with the 1996 visit of the Los Angeles class nuclear powered attack submarine USS Hampton at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. On a damp and dreary Saturday, Aug. 3, 1996, Pilotte was joined by several of his good friends: Hampton resident Brett Griffin, a crewman aboard the USS Hampton; David Webb, a fellow diver; James Hartman, Chief Navy Diver aboard the USS Hampton; Commander Christopher Stethos, skipper of the USS Hampton and Hampton Selectman Brian Warburton with divers' help, laid a plaque under the water near where the St. George's anchor rests.

lobster crawled onto it, paused, looked

up at this strange group of divers as if

to say, "What are you guys doing in my

home?" Pilotte said.

Hird and Pilotte met for the first time at Plaice Cove on a cloudy morning in mid-September, about a hundred feet from where the St. George met her fate. Both men are now the same age, in their 50s, although their discoveries were made 30 years apart. They immediately laid charts out on top of the North Beach seawall along with copies of documents, photographs and news clippings about their discoveries.

Sitting together on a picnic bench outside Kennedy's Restaurant at North Beach, the two men seemed like old friends, talking excitedly about their finds. Hird appreciated the plaque marking the spot of the old mast ship. "I feel what Larry did was exceptional to place a plaque next to the anchor in the same area where I had discovered the cannon," he said. Pilotte felt that the reunion and meeting of Hird was something of closure - "an exciting story that's finally coming together." It may be a matter of time, tides and the shifting sands before another piece of the St. George is revealed again.